Water, Water on the Wall, You’re the Fairest of Them All

Roni Horn: Water, Water on the Wall, You’re the Fairest of Them All

Museum of Contemporary Art Denver

1485 Delgany Street, Denver, CO 80202

September 12, 2025–February 15, 2026

Admission: Adults: $14, After 5pm Tuesday–Thursday: $5, Students and +65: $11, Members, Teens 13-18, and Children: free

Review by José Antonio Arellano

As its title begins to indicate, the exhibition Water, Water on the Wall, You’re the Fairest of Them All, curated by Nora Burnett Abrams, draws from Roni Horn’s decades-long exploration of the paradoxical identity of water. Paradoxical because what, after all, is more familiar yet literally ungraspable? What is more ubiquitous, yet so distressingly scarce?

Roni Horn, Doubt by Water, 2003-04, two-sided pigment prints in plastic sleeves on aluminum stanchions and photographs, each 16.5 x 22 inches, stanchions each 14 inches in diameter x 70.5 inches in height. Image courtesy of the Museum of Contemporary Art Denver.

The exhibition brings together a diverse collection of media, ranging from massive cast glass objects to a recorded performance of Horn reading her monologue "Saying Water." “What do you know about water?” asks Horn in the recorded performance. “When you talk about water, what is it you’re really talking about?” [1] The video shows Horn sitting at a desk outdoors as the sun sets behind her. Like the still surface of deep water, the simplicity and directness of her interrogation could mask its profundity. “What do you know about water?” she repeats. “When you talk about water, aren’t you really talking about yourself? Isn’t water like the weather that way?” [2]

Following this set of questions, I could say that Horn’s investigation into water’s mysteries might disclose more about herself and/or an “us,” the identity of which is perhaps as difficult to comprehend as her object of inquiry. The polished tops of the solid cast glass objects look so much like water that I must stop myself from touching them to make sure they’re not.

An installation view of Roni Horn’s (from left to right) Untitled (“The actual is a deft beneficence.”) and Untitled (“It was as though even the air in this region had barbed wire round it.”), 2023–24, solid cast glass with as-cast surfaces, 11 x 48 inches in diameter. Image courtesy of the artist and the Museum of Contemporary Art Denver.

A green glass object reminds me of a plastic kids' pool; the unpolished sides look like sugary candy. I know another of Horn’s cast glass objects that is also green, with the subtitle We have to recognize that someone who tortures people from 8 a.m. to 4 p.m. can still be a loving father at home. I consider the uncomfortable contradictions of my life as I look down at my reflection.

Whereas Snow White’s Evil Queen asks the magic mirror to reveal who is “fairest,” the exhibition’s title addresses water itself, as if it possessed an identity capable of being addressed. Insofar as “water” rhetorically becomes a mirror that reflects “us,” it is more of an opaque screen on which we project our desires and fears.

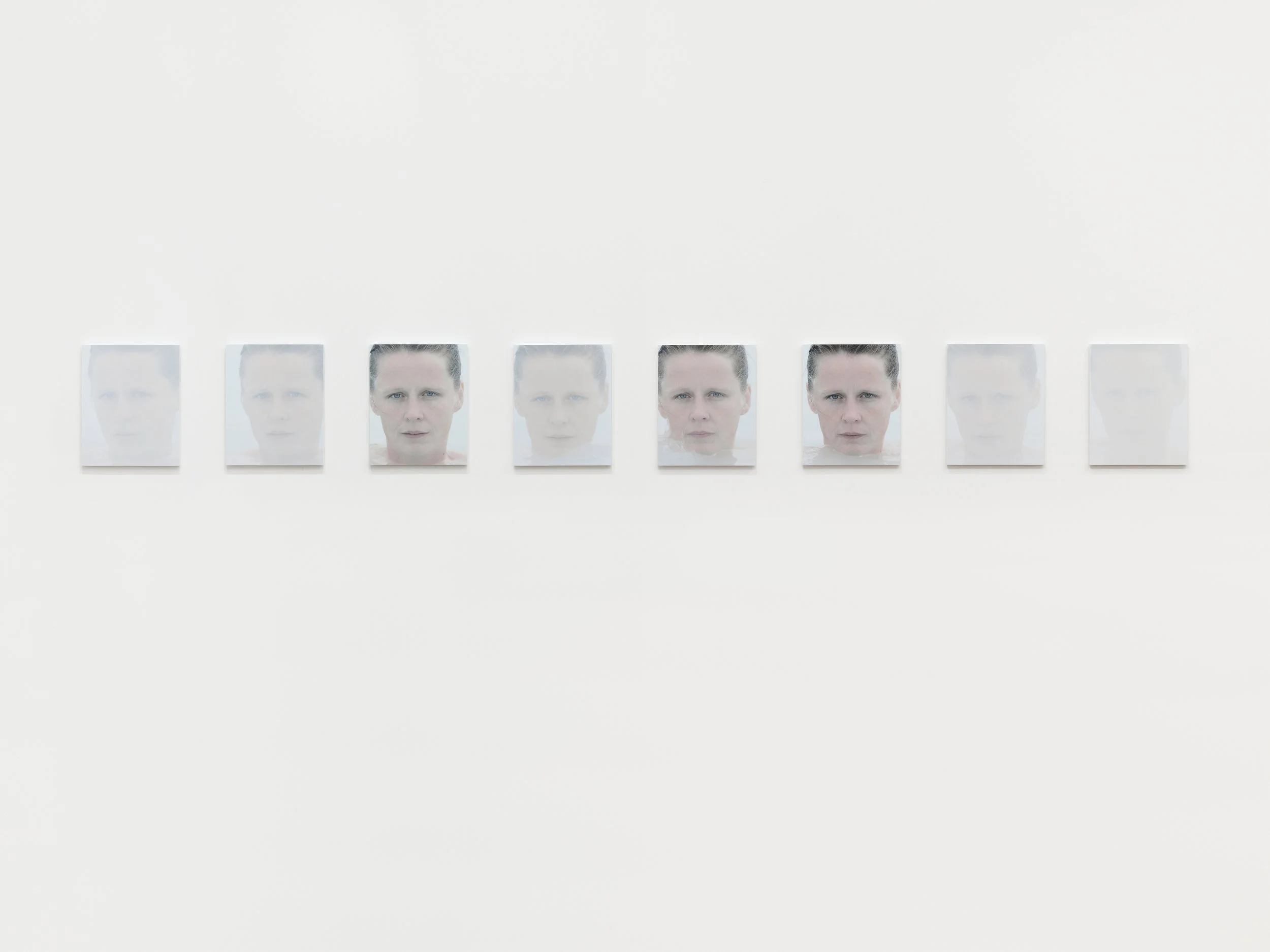

An installation view of Roni Horn’s You are the Weather, Part 2, 2010–11, pigment prints on paper, 66 color prints, 34 black and white prints, 100 units, each 10.4 x 8.4 inches. Image by JJY Photo, courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth.

I want to suggest, though, that Horn reveals more about the identity of artistic form than the viewing public that this form constitutes. Take, for example, the installation You Are the Weather, Part 2. Comprising one hundred photographs of the same woman, this installation encompasses the gallery. Photographs are hung on the gallery’s four walls in groupings of six to eight images displayed at eye level.

Crossing the gallery’s entrance is not exactly off-putting; the photographs are not large enough for that effect. And yet, the directness of the subject’s gaze, the affect of which shifts slightly in each photograph, confronts the viewer with a degree of inscrutability that faces so often present. Not the “Gen Z stare” nor the “deadpan” described by Tina Post, these photographs remind me of the “facingness” in Manet's paintings as described by Michael Fried. [3]

An installation view of Roni Horn’s You are the Weather, Part 2, 2010–11, pigment prints on paper, 66 color prints, 34 black and white prints, 100 units, each 10.4 x 8.4 inches. Image by JJY Photo, courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth.

Yet this anachronistic, de-mediated comparison is not entirely apt. These are, after all, photographs, and as such, their subject and setting are necessarily particularized. Horn photographed Icelandic artist Margrét Haraldsdóttir as she emerged from a number of Icelandic hot springs. I learned that Horn uses Haraldsdóttir’s face to evoke the landscape and weather, both of which are not at the forefront of the images. Haraldsdóttir captures the weather not by representing it but by existing within it. She metaphorically “is” the weather the way Shakespeare’s Juliet is the sun.

A detail view of Roni Horn’s You are the Weather, Part 2, 2010–11, pigment prints on paper, 66 color prints, 34 black and white prints, 100 units, each 10.4 x 8.4 inches. Image by JJY Photo, courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth.

The water remains visible on her face and hair; her eyelashes bear its weight. The close-up shots are off-center often enough to foreclose the genre of portraiture. Her hair and the side of her face are sometimes cropped, implying that the individual pictures are part of a series and not themselves the point.

This impression is amplified by the groupings of photographs interrupted by the gallery’s architecture. The gallery entrances and corners get in the way, but one can tell that this interruption is not the point either. The groups of photographs persist within the whole of the installation’s form despite the physical conditions that display it.

A detail view of Roni Horn’s You are the Weather, Part 2, 2010–11, pigment prints on paper, 66 color prints, 34 black and white prints, 100 units, each 10.4 x 8.4 inches. Image by JJY Photo, courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth.

With the title’s mention of other iterations of this series (this is “Part 2”) though, one wonders what the meaning of “whole” could be in relation to this series’ “form.” That totality, perhaps, resembles water’s, wherein the water in my glass is connected to the water in Antarctica, connected to the water that, I am told, constitutes half of your body and mine.

I can imagine this installation hung within a round, doorless space. No temporal, linear narrative; no beginning or end. Although I might think that the photographed subject is looking directly at me, in reality she is looking at the camera that produces the occasion for her expressions. What does it mean, then, that the series refers to a “You” as “the weather”? Whom does the title address? “Me” or Haraldsdóttir? Perhaps the installation imagines the possibility of creating its own environment wherein it addresses itself. [4]

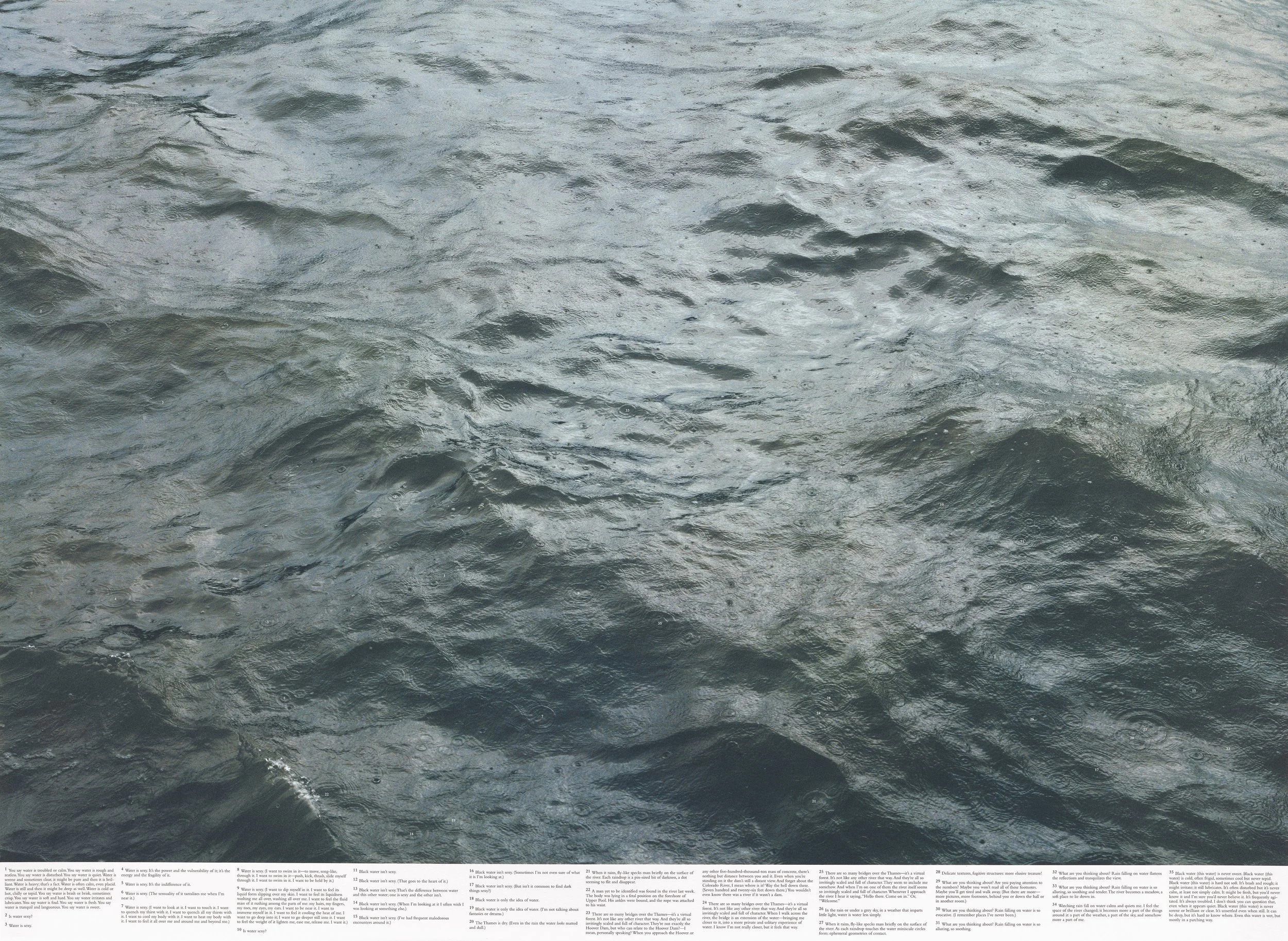

A detail view of Roni Horn’s Still Water (The River Thames, for Example), 1999, photographs and text printed on paper, 15 units, each 30.5 x 41.5 inches. Photo by Ron Amstutz, courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth.

The power of Horn’s photographs renders in form an aesthetic identity that nature as such cannot produce. We can never see the water itself apart from how it is framed in the pictures of Still Water (The River Thames, For Example.) By pushing it forward so that it fills the entire photograph, the shape of this water is the shape of the photograph itself, which frames an identity that is inseparable from the form that brings it into being. [5]

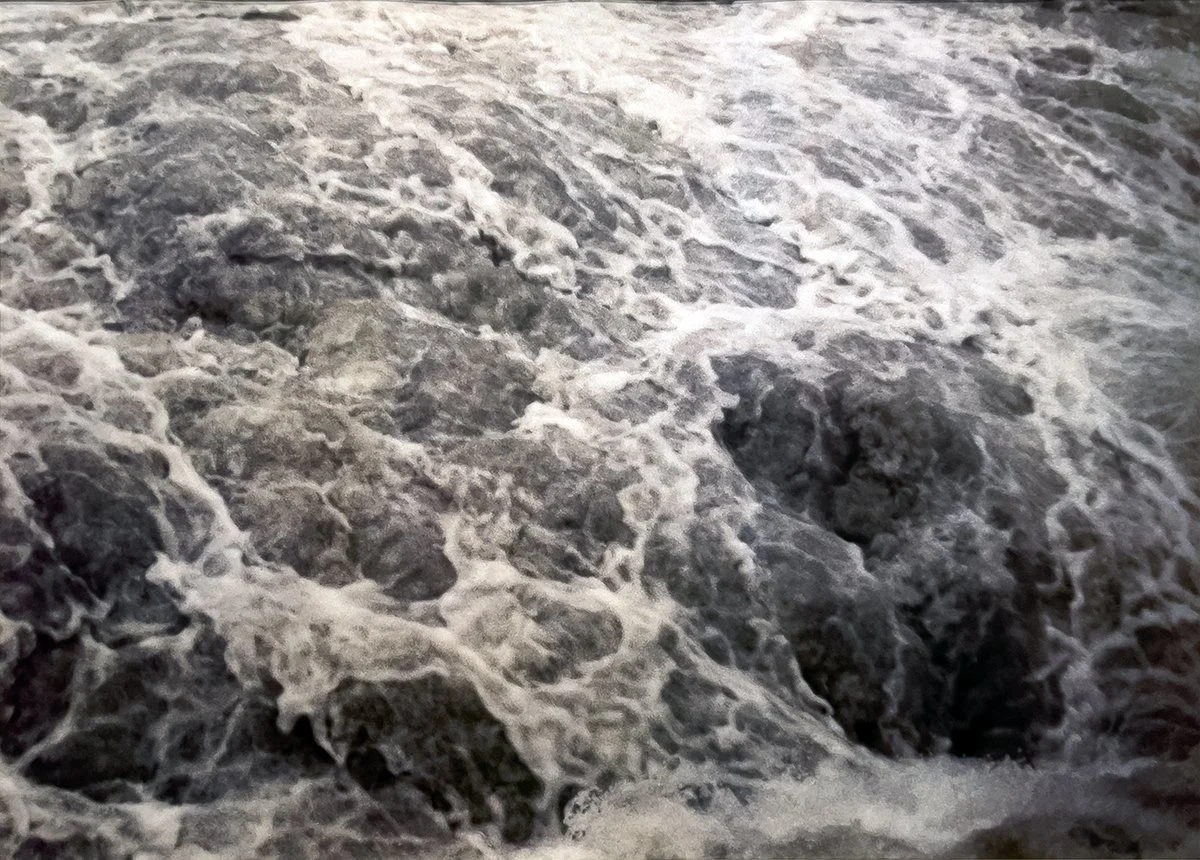

Two photographs in Roni Horn’s Pooling—You, 1996–1997, photographs on paper, 7 units, each 42 x 58 inches. Image by José Antonio Arellano.

Whereas the photographs in this series include text within the bottom margin, with questions about the slippery identity of water, no text appears in the full-bleed photographs of the series Pooling—You. I recall the Russian Formalist Viktor Shklovsky’s concept of defamiliarization, in which art slows down and reinvigorates perception by “return[ing] sensation to our limbs, in order to make us feel objects, to make the stone feel stony.” [6] The defamiliarizing effect evident in these photographs, however, is more extreme.

One photograph in Roni Horn’s Pooling—You, 1996–1997, photographs on paper, 7 units, each 42 x 58 inches. Image by José Antonio Arellano.

Water, here, does not feel more watery; the opposite is true. Some photographs zoom in on water so much so as to pixelate and granulate its appearance. Water becomes so formalized as to approximate abstraction. This is water as I have never seen it and never will, because what I am looking at is not a re-presentation of nature; it is an achievement that takes the name of art.

Roni Horn, Key and Cue, No. 135, WATER, IS TAUGHT BY THIRST, 1994/2007, solid aluminum and cast black plastic, 54 x 2 x 2 inches. Photo by JJY Photo, courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth.

Horn explores the achievement that is artistic form by fragmenting existing instantiations of it. In Key and Cue, No. 1740, Horn excises and materializes lines from Emily Dickinson’s poems, converting the poetic line—the paradigmatic source of the poet’s power—into a three-dimensional bar in space. The letters of Dickinson’s alliterative line “Sweet is the swamp with its secrets” bleed around the bar’s edges, becoming illegible. Leaning against the wall, what had been a poetic line is now subjected to the force of gravity.

A detail view of Roni Horn’s Still Water (The River Thames, for Example), 1999, photographs and text printed on paper, 15 units, each 30.5 x 41.5 inches. Photo by Ron Amstutz, courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth.

I could say that the significance of this exhibition becomes more urgent in Colorado—a state whose dryness cracks my skin and makes me bleed. But there is the significance that accrues, and the meaning that abides. The former (significance) is the function of changing contexts; the latter (meaning) is a function of formal embodiment. Wherever we happen to view Horn’s achievement, it is the latter that will persist.

José Antonio Arellano (he/him) is an Associate Professor of English and fine arts at the United States Air Force Academy. He holds a Ph.D. in English language and literature from the University of Chicago. He is the author of Race Class: Reading Mexican American Literature in the Era of Neoliberalism, 1981-1984, which was published by Cambridge University Press in 2025.

[1] Nora Burnett Abrams, et al. Roni Horn: Water, Water on the Wall, You’re the Fairest of Them All (Rizzoli Electa, 2025), 156.

[2] Ibid.

[3] See Tara Well, “The Psychology Behind the Gen Z Stare.” Psychology Today, August 18, 2025; Tina Post, Deadpan: The Aesthetics of Black Inexpression (from Minoritarian Aesthetics), (New York: NYU Press), 2023; and Michael Fried, Manet’s Modernism: Or, The Face of Painting in the 1860s (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996).

[4] See Thierry de Duve, “Focus: You Are the Weather,” in Roni Horn, ed. Lynne Cooke and Louise Neri (London: Phaidon Press, 2000), 78-85.

[5] See Walter Benn Michaels’ reading of James Welling’s photographs in The Shape of the Signifier: 1967 to the End of History (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2004), 100-105.

[6] Viktor Shklovsky, “Art as Device,” in Theory of Prose, trans. Benjamin Sher (Elmwood Park: Dalkey Archive Press, 1991), 6.