Rosas y Revelaciones: Homage to the Virgin of Guadalupe

Rosas y Revelaciones: Homage to the Virgin of Guadalupe

Museo de las Americas

861 Santa Fe Drive, Denver, CO 80204

October 16, 2025–January 11, 2026

Admission: General Admission: $8 Students, Seniors, Artists, Teachers, and Military: $5 Members: Free Children 13 and under: Free

Review by José Antonio Arellano

During a family trip to Mexico City in 1959, Linda Hanna was moved by the devotion shown by peregrinos—those making the pilgrimage to the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe. These pilgrimages can be painful, as many choose to arrive at the shrine on bloodied knees. Although she was not raised Catholic, the memory of sacrifice and devotion left an impression on Hanna. Decades later, she found her own way to pay homage to The Virgin.

An installation view of the exhibition Rosas y Revelaciones at the Museo de las Americas in Denver. Image by Dariel Almeida, courtesy of the Museo de las Americas.

After moving to Oaxaca in the late 1990s, she began to learn about the region's remarkable diversity and complexity in textile artistry. For years, Hanna has commissioned artisans to recreate the image of Guadalupe on clothing traditional to their regions and tribes. She has built a collection that she plans to donate to her adopted country. Part of this collection is now on display at the Museo de las Americas in the exhibition Rosas y Revelaciones.

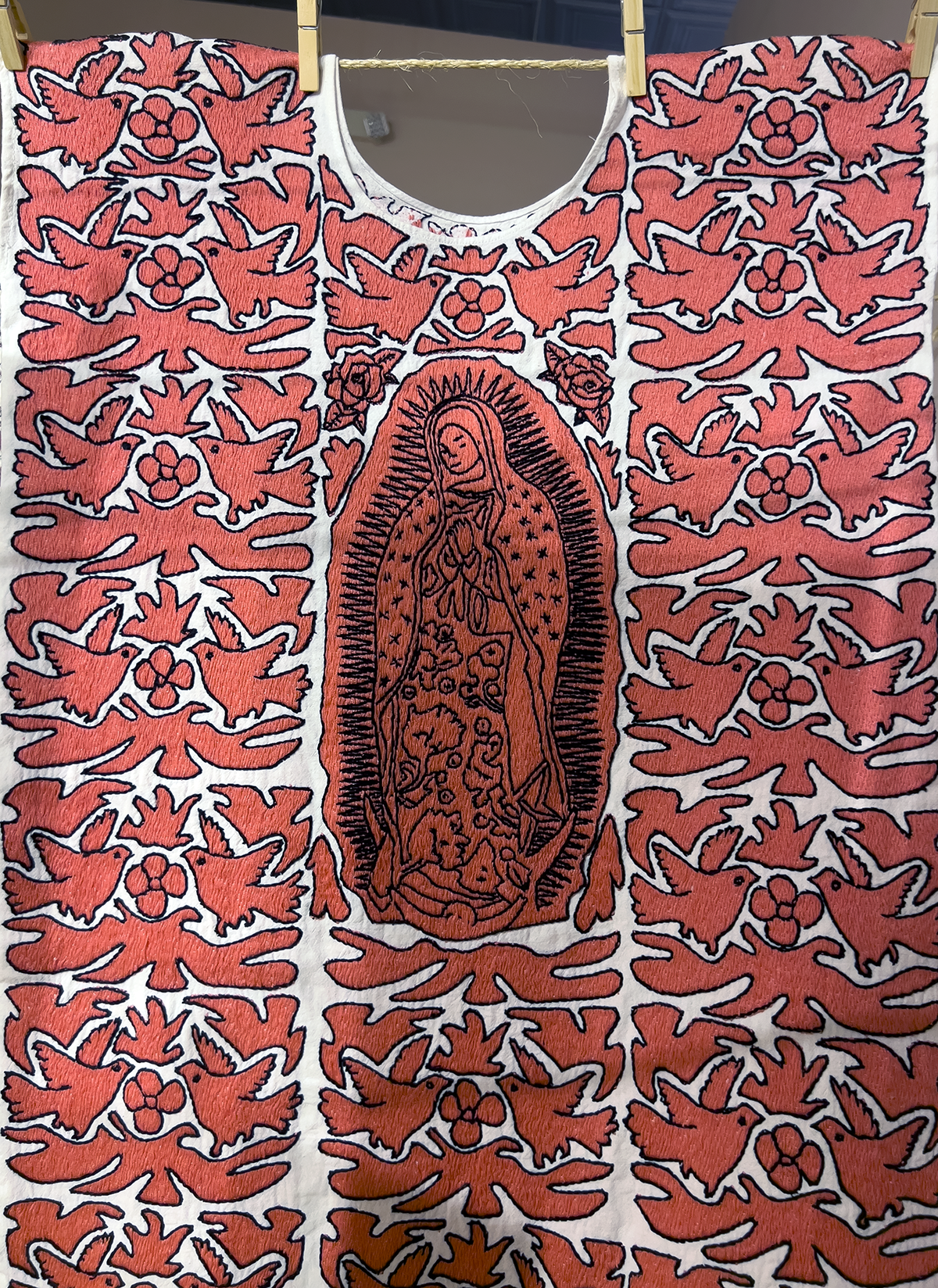

A view of three garments featuring images of the Virgin of Guadalupe commissioned by Linda Hanna. Image by Dariel Almeida, courtesy of the Museo de las Americas.

El Museo de las Americas is ideally positioned in Denver to display these remarkable works. Since the early 1990s, the museum’s mission has focused on educating the public through exhibitions showcasing Latin American cultural expressions. Even visitors already familiar with Mexican traditional dress can learn about the great diversity in skills and attire of the represented regions.

An installation view of the exhibition Rosas y Revelaciones at the Museo de las Americas in Denver. Image by Dariel Almeida, courtesy of the Museo de las Americas.

Each state of Mexico has a traje típico—a traditional dress that represents its regional identity. However, in this exhibition, the many blouses and huipiles from Oaxaca alone showcase the diversity of styles that cannot be captured in a single example. The exhibition includes work by Indigenous peoples, including the Zapotec, Mixtec, Huichol, Mazatec, and Nahua.

Teresa Borja Pérez, San Bartolomé Ayautla, Oaxaca (Mazateco), huipil made of unbleached muslin, embroidered with the technique of “Maya” stitch, a variant of puntada de hilván, running stitch, with the image of The Virgin on the front and back. Image by José Antonio Arellano.

Wearable textiles are an especially apt form of homage to the legend of the Virgen de Guadalupe. Her image has beguiled viewers since the sixteenth century, when an origin myth began to develop. According to the legend, in 1531, the Virgin of Guadalupe appeared to an Indigenous man named Cuauhtlatoatzin (who took the name Juan Diego when baptized by Franciscan missionaries).

The Virgin—speaking Nahuatl— asked him to have a basilica constructed in her honor and told him to collect out-of-season roses that miraculously grew on the site as proof of her presence. He gathered the flowers in his traditional tilma, a woven cloak. When he let down his tilma to show the bishop the flowers, an image of Guadalupe had miraculously been imprinted.

The image merges Christian motifs and Indigenous symbolism, presenting the Virgin as an Indigenous woman whose darker skin contrasts with the history of European Christian iconography. It has been used by ruling elites and reclaimed by the disenfranchised. [1]

Crispina Navarro Gómez, Santo Tomás Jalieza, Oaxaca (Zapoteco), miniature bag woven in five strips on a telar de cintura, a back-strap loom, with fine gauge commercial cotton thread, and supplementary warp patterning with The Virgin in the third strip, only on the front. Image by José Antonio Arellano.

When I visited the exhibition, I wondered whether the artisans viewed Hanna’s criterion—the textiles she commissions must feature the Virgin of Guadalupe—as an imposition foreign to their Indigenous practices and beliefs. Although the image of Guadalupe is widely recognized and well-known throughout Mexico, it can justifiably be seen in the context of a history of colonization.

Hanna described the artisans’ quiet hesitation, which did not appear to her as resistance but as an acknowledgement of the practical difficulty of her request. Because the image is not part of their textile vernacular, they would have to develop new methods for rendering it.

Erasto (Tito) Mendoza Ruiz, Teotitlán del Valle, Oaxaca (Zapoteco), ruana woven on a treadle loom with naturally dyed cotton thread. The two images of the Virgin are woven with wool and metallic threads using a tapestry technique. The fringe is finished in macramé. Image by José Antonio Arellano.

I was fascinated by how many artisans reclaimed the image by incorporating it into their visual vernacular and symbology. Erasto (Tito) Medoza Ruiz, for example, arrays the Virgin in the traditional Zapotec patterns used in clothing and architecture.

Teófila Servín Barriga, Tzintzunzan, Michoacán, dress made of cotton woven on treadle loom and embroidered using the technique of punto al passado, back stitch. Image by José Antonio Arellano.

Detail of Teófila Servín Barriga, Tzintzunzan, Michoacán, dress made of cotton woven on treadle loom and embroidered using the technique of punto al passado, back stitch. Image by José Antonio Arellano.

A dress by Teófila Servín Barriga features embroidered vignettes depicting life in Tzintzunzan, Michoacán. The dress serves to document a way of life, however idealized, to the museum visitors. In a vignette depicting two women working while wearing traditional aprons, one can even detect what I read as the traces of the artist’s abbreviated name: Teo.

An arrangement of garments by Adela de la Cruz, Olivia y Alina Carrillo Cruz, and Teresa Borja Pérez in the exhibition Rosas y Revelaciones at the Museo de las Americas. Image by José Antonio Arellano.

A shirt in the center of the picture above, made by Huichol Indigenous artisans Adela de la Cruz and Olivia y Alina Carrillo Cruz, notably flanks the Virgin with flowering corn stalks—a meaningful spiritual symbol for the Huicholes. In the huipil shown to the right of this shirt the artist Teresa Borja Pérez uses a Mayan stitch to depict a dark-skinned Virgin along with a symbolic Zapotec two-headed bird.

Maria Trinidad González García, Paracho, Michoacán (Purépecha), naturally dyed cotton rebozo with the image of The Virgin, brocaded on a backstrap loom with double-weaved technique. Image by José Antonio Arellano.

Maurilia Pascual Martínez, Oaxaca, Oaxaca (Zapoteco), commercial cotton blouse, hand-led machine embroidered with polyester thread. Image by José Antonio Arellano.

Some of the pieces materialize the contested racial politics embedded in the Guadalupe legend. The natural dyes of a double-sided rebozo by Maria Trinidad González García appear to comment on the duality of The Virgin’s racialized symbolism. Some pieces, including Maurilia Pascual Martínez’s blouse, make the Virgin’s racialization explicit.

Jan Christian Mata Ferrer, San Felipe Santiago, Villa de Allende, Estado de México (Mazahua). Image by José Antonio Arellano.

Tepeyac, the site where The Virgin is said to have appeared, had been a place of worship for a Mesoamerican “Tonantzin,” meaning “Our Sacred Mother.” Jan Christian Mata Ferrer depicts Guadalupe with the attributes of a Mesoamerican deity—on a backdrop of green, white, and red—suggesting a syncretism available in Mexican history.

Faustina Sumana García, San Juan Chilateca, Oaxaca (Zapoteco), blouse of poplin cotton with the image of The Virgin and flowers embroidered in the technique of punto al passado, back stitch. Also, the technique of pepenado fruncido, to make “Hazme si puedes.” Sleeves added with a decorative crochet stitch, also used to finish the neck and sleeve bottoms. Image by José Antonio Arellano.

The precision visible in these textiles—the regularity of stitches, the controlled tension of warp and weft, the calculated density of embroidered motifs—is embodied in memory and practice without the aid of templates, written patterns, or diagrams. The textiles materially manifest the skills learned through years of observation and tactile experience.

The complexity evident in the weaving and embroidery reveals layers of knowledge and skill that demonstrate an intimate understanding of how fiber behaves, how tension affects pattern, and how color relationships emerge through the accumulation of thread. This knowledge circulates orally, passed from one generation to the next via the act of making itself.

María Guadalupe Santiago Sánchez, San Antonino Castillo Velasco, Oaxaca (Zapoteco), linen blusa embroidered with rayon thread using the techniques: satin stitch, camalache, pulled thread, and “Hazme si puedes.” The image of The Virgin on the front, back, and both shoulders. Edges finished with crochet trim. Image by José Antonio Arellano.

Detail of María Guadalupe Santiago Sánchez, San Antonino Castillo Velasco, Oaxaca (Zapoteco), linen blouse, rayon thread, satin, crochet trim. Image by José Antonio Arellano.

The blusa pictured above, for example, demonstrates a virtuosic command of multiple techniques working in concert, with geometric patterns that converge to create flower motifs worked in satin stitch. The maker, Santiago Sánchez, did not think it was possible to create the figure of the Virgin using the techniques she knew. And yet, through the smocking technique called “Hazme si puedes,” she succeeded. The technique’s name translates to “Make me if you can,” simultaneously expressing a challenge and pride in the accomplishment.

An installation view featuring baules, cedar chests, used to transport and protect clothing in the exhibition Rosas y Revelaciones at the Museo de las Americas. Image by José Antonio Arellano.

Maruca Salazar, who was the previous director of the Museo de las Americas for nearly a decade, returned to the museum to curate the exhibition. Instead of relying on mannequins to display the array of garments, Salazar created a series of installations that invoke the social life of the clothes. [2] Salazar’s curatorial strategy resists presenting the textiles as static objects by emphasizing their use—their washing, warming, storage, and transportation.

An installation vignette with stones evoking river stones and hand washing in the exhibition Rosas y Revelaciones at the Museo de las Americas. Image by José Antonio Arellano.

Salazar stages intimate vignettes meant to evoke cultural practices: blusas swaying on clotheslines as a fan mimics the breeze that will dry them; rebozos hung on ladders, as if next to a fireplace, to warm them; dresses spread on stones, meant to evoke handwashing in a river.

An installation vignette featuring a wooden wardrobe and clothing depicted as erupting out of the storage cabinet in the exhibition Rosas y Revelaciones at the Museo de las Americas. Image by José Antonio Arellano.

In one of the exhibition’s central installations, Salazar imagines clothing bursting out of a wooden wardrobe and taking flight. Suspended from the ceiling by ropes, the clothes appear lifted by invisible forces. I take this imaginative flourish as a reference to the image of Guadalupe, which depicts an angel holding her mantle and the hem of her tunic, not visibly supporting her body.

An installation view of the clothes suspended from the ceiling with ropes in the exhibition Rosas y Revelaciones at the Museo de las Americas. Image by José Antonio Arellano.

Salazar reconsiders the museum experience by installing a tenderero, a place to hang clothes out to dry, involving more than thirty huipiles and blusas. Visitors are invited to walk through the tenderero. I only wish that the names of the artisans and details of each wonderful piece were more accessible to the viewer.

The poet Pablo Martinez reminds us that the Spanish verb “tender” describes the act of hanging laundry out to dry, whereas in English the adjective “tender” evokes softness and sensitivity. [3] The tender act of caring for clothing, as represented in the installation, reminds me of the love I have experienced in my life as expressed in such acts.

An installation view of a tenderero, a place to hang clothes to dry using clothes line, in the exhibition Rosas y Revelaciones at the Museo de las Americas. Image by José Antonio Arellano.

I am also reminded of how my mother would interact with her friends and relatives as she observed a new crochet pattern in a blanket or an unfamiliar stitch on a blouse, the delight in her eyes as she would ask to gently handle the material, turning it over to observe the technique. I could not understand how she could untangle the complex artistry in her mind. [4] When she was stumped, my mother would ask, “Will you teach me how to make this?”

There were no degrees conferred for the skill, no museum exhibitions, no opening nights to acknowledge the accomplishment, and no critical fanfare to celebrate and understand the achievement. Instead, the women I witnessed would often share an unspoken acknowledgment: This is well made. This is beautiful. I can teach you how it is done.

An installation view of wooden ladders used as warming racks in the exhibition Rosas y Revelaciones at the Museo de las Americas. Image by José Antonio Arellano.

Each of the items on display in Rosas y Revelaciones embodies a part of its maker, their vision, and the meaning of the work as it is embedded in their way of life. There is a tangible sense of devotional sacrifice in these pieces, of aching bodies that continue to create, and of the time involved in each stitch. This is a sacrifice that honors the creative spirit, whatever name we give it, whatever language it speaks, out of which life itself emerges.

José Antonio Arellano (he/him) is an Associate Professor of English and fine arts at the United States Air Force Academy. He holds a Ph.D. in English language and literature from the University of Chicago. He is currently working on two manuscripts titled Race Class: Reading Mexican American Literature in the Era of Neoliberalism, 1981-1984 and Life in Search of Form: 20th Century Mexican American Literature and the Problem of Art.

[1] See Jeanette Favrot Peterson, "The Virgin of Guadalupe: Symbol of Conquest or Liberation?" Art Journal, vol. 51, no. 4, Winter 1992, pp. 39-47. For an art historical account of the image’s origins, see Jeanette Favrot Peterson, "Creating the Virgin of Guadalupe: The Cloth, The Artist, and Sources in Sixteenth-Century New Spain." The Americas, vol. 61, no. 4, April 2005, pp. 571-610. The image became important for Chicana feminist artists, including Ester Hernández and Yolanda López, who reimagine and reconfigure the image to speak to contemporary decolonial politics.

[2] In the edited volume The Social Life of Things, the cultural anthropologist Igor Kopytoff describes a methodology he calls “the cultural biography of things.” “In doing the biography of a thing,” writes Kopytoff, “one would ask questions similar to those one asks about people.” Such questions could include, “Where does the thing come from and who made it? What has been its career so far, and what do people consider to be an ideal career for such things? What are the recognized ‘ages’ or periods in the thing’s ‘life,’ and what are the cultural markers for them?” Kopytoff, Igor. “The Cultural Biography of Things: Commoditization as Process.” The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective. Ed. Arjun Appadurai. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986. 67.

[3] See José Antonio Arellano, "A Hopeful Eulogy: Pablo Miguel Martinez's Poem about the Longoria Affair." War, Literature & the Arts: An International Journal of the Humanities, vol. 33, 2021, https://www.wlajournal.com/_files/ugd/134164_84ea17b962da488f81d694acb316c983.pdf.

[4] The ancient Greeks, I would later learn, called such a skill analysis—the act of undoing something completely to learn how it works. I recall learning about Homer’s Odyssey, in which a woman, Penelope, expresses her agency by weaving and unweaving, creating and analyzing.