It Comes in Waves

It Comes in Waves

The People’s Building

9995 E Colfax Avenue, Aurora, CO 80010

November 7-December 30, 2025

Curator: Heather Schulte

Admission: free

Review by Raymundo Muñoz

With all the political controversies, conspiracy theories, and heated disagreements about safe and effective treatments surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic, it’s easy to forget it all happened. For some, though, forgetting is not so easy; many are still living with the after-effects of the COVID infection. These Long COVID sufferers have and continue to endure a slew of maladies related to the illness, upending and interrupting their lives in myriad ways.

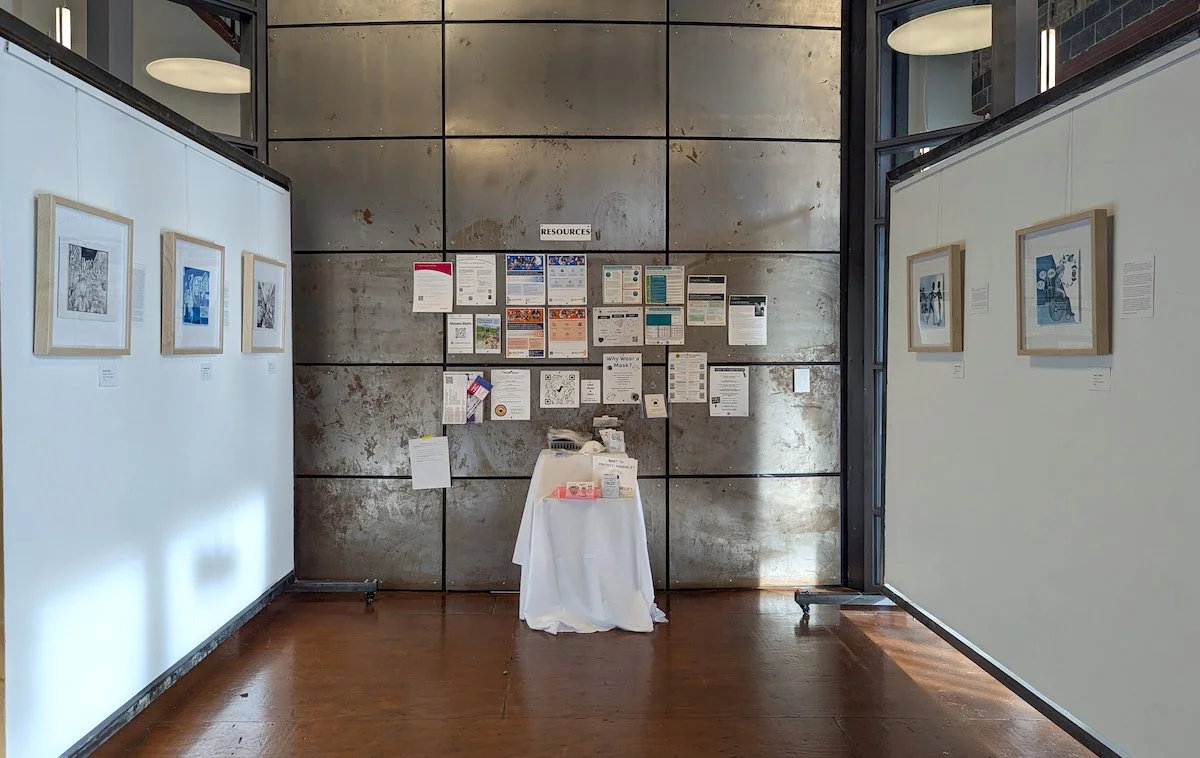

An installation view of the exhibition It Comes in Waves at The People’s Building in Aurora, Colorado. Image by Raymundo Muñoz.

On display at the People’s Building in Aurora, Colorado, It Comes in Waves is a group exhibition about Long COVID (abbreviated LC) in Colorado, curated by Denver-based artist Heather Schulte. Part of her Stitching the Situation COVID-themed community embroidery project, Schulte expanded on this idea by conducting numerous interviews with people suffering from LC, some of whom created artworks or poetry based on their struggles.

Schulte adds an interesting element to this project by also commissioning Colorado inmates to create artworks that draw inspiration from her interviews. It Comes in Waves is a heavy, painful exhibition that explicitly details the physical, psychological, and emotional struggles of LC sufferers in Colorado, further interpreted through the lens of incarceration. But also on display are glimmers of hope and healing through sheer resilience and finding understanding and support near and far.

Douglas “DC” Lehman, Hero, 2020, pencil, colored pencil, and ink on paper, 9 x 12 inches. Image by Wes Magyar.

At the front of the exhibition, you’re confronted with Hero—a radical drawing of an overwhelmed nurse, depicted with face tattoos in colorful, graffiti-style lettering that says “First Responder,” “RX,” and “ESSENTIAL.” Created in 2020 by Douglas “DC” Lehman, a self-taught artist and inmate in the Colorado Department of Corrections, the piece shows gritty respect for healthcare workers, while also suggesting themes of identity and the permanent marks left by the pandemic.

An installation view of It Comes in Waves at The People’s Building. Image by Raymundo Muñoz.

Complicated struggles with the healthcare system come up repeatedly throughout the exhibition, from difficult medical treatments like hyperbaric oxygen therapy (for instance, in LEAVING THE FOG BEHIND by Sally Hartshorn) and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (see Barbara’s Story) to the inability to help and gaslighting by doctors (in Michaela’s Story) to the “stigma of disease in jails and prisons” (see Emerson’s Story) to changes in public masking policies.

Teague McDaniel and Venture Merz, Sitting with it, 2025, synthetic fiber masks, wood, and paper collage, 8 x 36 inches. Image by Raymundo Muñoz.

The issue of masking (i.e. their effectiveness and need), in particular, is given large credence in the exhibition. Consider Teague McDaniel and Venture Merz’s collaborative installation Sitting with it, composed of 100 dye-sublimated, synthetic fiber masks accompanied by written word components. Visitors are invited to take a mask and consider Merz’s experiences with LC and McDaniel’s abstract imagery of blurred video stills inspired by impermanence.

Lucy’s Story, illustrated by Sonny Lee, 2025, acrylic on paper, 9 x 9 inches. Image by Wes Magyar.

Additionally, Lucy Chester’s story Are you better?, illustrated by Sonny Lee, depicts a masked and wheelchair-bound Lucy, downtrodden by an incredulous group of people questioning her disabled experience from afar.

Karen Breunig, Red Dress #3, 2023, oil on canvas, 30 x 40 inches. Image by Raymundo Muñoz.

Indeed, the loss of health, independence, ways of life, and relationships are major themes across the board. Consider the textured, expressionistic oil paintings of Karen Breunig, a painter living with brain fog, dizziness, fatigue, and feelings of hopelessness from LC. Red Dress #3, for instance, depicts a forlorn and pale figure with a bright red dress hung on a tree, almost disintegrating into the green background and perhaps a reminder of the artist’s lost vibrancy.

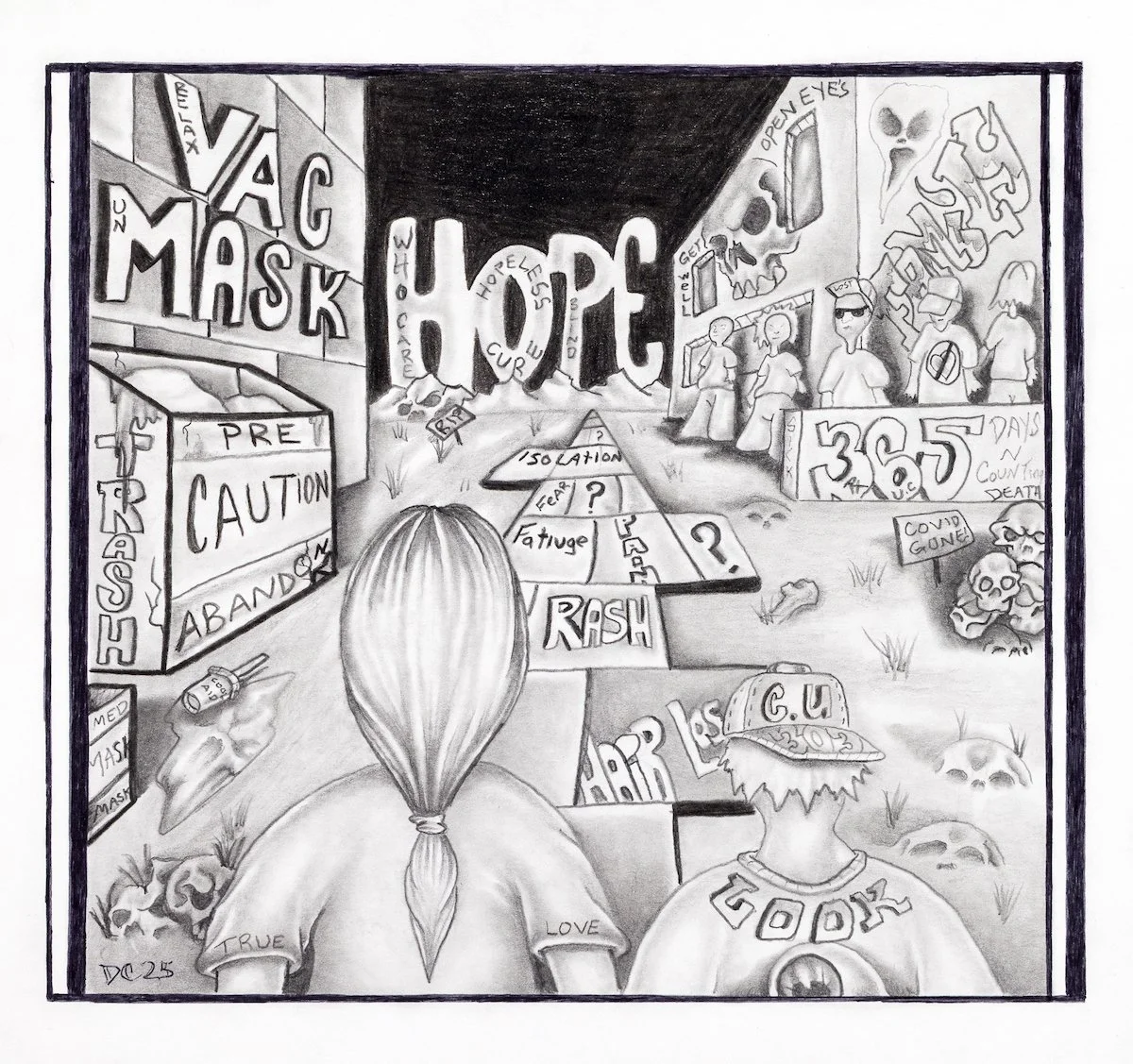

Carol’s Story, illustrated by Douglas “DC” Lehman, 2025, pencil and ballpoint pen on paper, 9 x 9 inches. Image by Wes Magyar.

Dani’s Story, illustrated by Douglas “DC” Lehman, 2025, pencil and ballpoint pen on paper, 9 x 9 inches. Image by Wes Magyar.

Carol Rathe’s story—intermittent relief through medication until briefly mopping the kitchen floor triggered a debilitating flare up of pain and exhaustion—is illustrated powerfully in pencil and ballpoint pen by Lehman. The incarcerated artist also illustrates Dani’s Story, a dark and harrowing account of family abandonment and the complications of caring for a high-risk child with additional health issues.

An installation view of Beth Meier’s (left) and Karen Breunig’s (right) work in It Comes in Waves at The People’s Building. Image by Raymundo Muñoz.

In another way, Beth Meier’s A Life Redacted deals with loss through redacted transcripts taken from A Friend for the Long Haul podcast, offering emotionally-charged fragments of living and being a parent with LC. Presented in this way, the conversation is boiled down to a visual poetry of black lines and what remains.

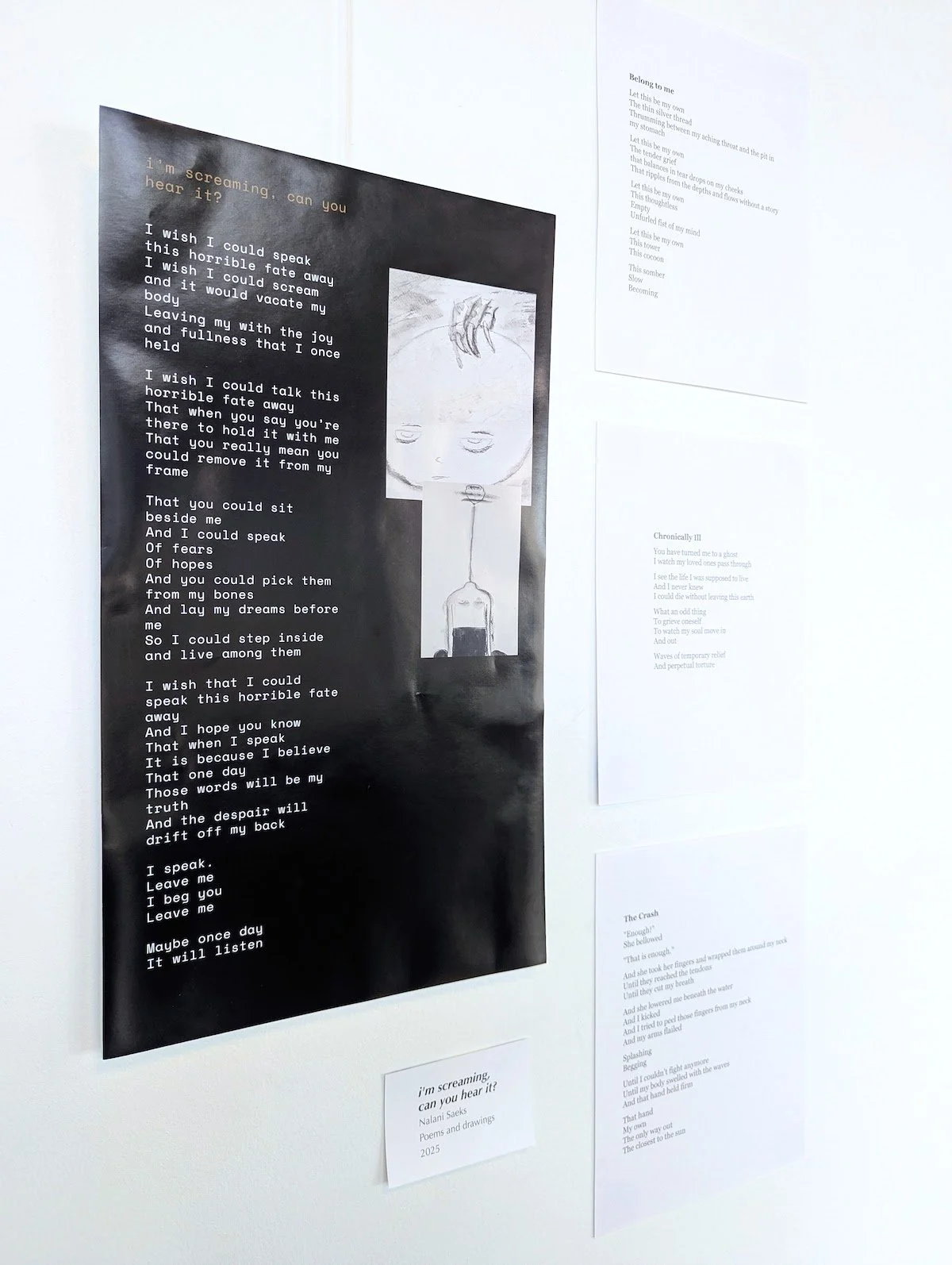

An installation view of poems by Nalani Saeks in It Comes in Waves. Image by Raymundo Muñoz.

Colorado-based poet Nalani Saeks meanwhile relates her own LC experiences through evocative poems like “I’m screaming, can you hear it?” and “Chronically Ill.” The latter, in particular, relates to the exhibition’s title and refers to feeling like a ghost with “waves of temporary relief / And perpetual torture.”

As hellish as these accounts are, curator Heather Schulte balances the shared pain with stories of resilience, hope, and healing, while offering informational resources on dealing with LC.

Michaela’s Story, illustrated by Hector Castillo, 2025, acrylic on paper, 9 x 9 inches. Image by Wes Magyar.

Michaela’s Story, illustrated in acrylic on paper by Hector Castillo, depicts a smiling Michaela Martinez with her family and supportive medical staff. After getting sick with LC at 33 and losing her ability to care for her children, Martinez slowly began to heal with support from her husband and co-founded the Long COVID Information, Discussion, and Support Group to help others dealing with LC.

Sophia’s Story, illustrated by Sonny Lee, 2025, acrylic on paper, 9 x 9 inches Image by Wes Magyar.

Riccardo Kirven’s illustrations offer images of resilience with hard-won steps to wellness (in Barbara’s Story) and an uphill race to an LC cure (against a cartoon band of COVID viral particles) (see Frances’ Story). Similarly, Sonny Lee depicts a figure breaking the chains of years with COVID in Sophia’s Story, echoing the assertion that recovery is possible and still a struggle, but one that is hopeful.

An installation view of works by AnaKacia Shifflet, Karen Breunig, Nalani Saeks, and Karin Dove (left to right) in It Comes in Waves at The People’s Building. Image by Raymundo Muñoz.

Others find healing through artmaking. Karin Dove, for instance, steadily lost her “hobbies, career, a social life, aspirations, and independence” after contracting LC, but found reinvention and meaning through birding, an activity that replaces hiking and still connects her with nature. Her digital illustration Flight Path depicts a flock of birds flying in the same direction—a reference to her new hobby.

Sally Hartshorn, THE PROTECTOR, wool, felt, wood, feather, paper, mixed media, and metal. Image by Raymundo Muñoz.

Retired RN Sally Hartshorn’s mixed media sculptures reflect on healing through combinations of soft materials like silk, wool, and yarn with natural objects like found wood and feathers. THE PROTECTOR, in particular, represents the artist’s need for a protector and support system (e.g. her husband) to help her “reintegrate into the functioning world.” And AnaKacia Shifflet dealt with her debilitating illness in a cathartic way through dressmaking and throwing paint in her work The Painted Dress.

AnaKacia Shifflet, The Painted Dress, 2020, fabric and paint. Image by Raymundo Muñoz.

On this note, I can’t fail to mention the experiences of the incarcerated artists themselves. While their experiences are fundamentally different in ways (e.g. quarantine by choice versus forced solitary confinement), there are indeed strong similarities in feelings of pain, isolation, abandonment, and loss of control, in general and in ways specific to COVID.

Consider the visual parallel of LC sufferers being bed-ridden with the experience of inmates in small cells with only a bed to sit on. Bearing in mind the creative collaborations of the exhibition, incarcerated artist Hector Castillo relates in his statement that there’s a “common thread of fortitude, whether physically incarcerated or feeling incarcerated in one’s own body.” Riccardo Kirven echoes this sentiment, remarking on LC survivors’ “never give up” mentality that’s similar to getting through and out of prison.

Emerson’s Story, illustrated by Mario Rios, 2025, ink on paper, 10 x 10 inches. Image by Wes Magyar.

Though not directly concerning Colorado inmates, Schulte also includes a digital screen from which visitors can access a website that deals with the similarities of COVID-19 and HIV/AIDS within those incarcerated in Missouri. Emerson’s Story, illustrated by Mario Rios, is based on an interview with Emerson Morris, a recent transplant from Missouri and LC survivor, that asserts “We have each other if nothing else” around a symbol of gender inclusivity.

In an exhibition brimming with narratives, art, and informational resources, this section of the exhibition may be too much, perhaps conflating more issues than needed and reaching beyond the exhibition’s conceptual and geographical bounds. On the other hand, it reiterates the dire need for community and support for those with LC.

An installation view of It Comes in Waves at The People’s Building. Image by Raymundo Muñoz.

Importantly, It Comes in Waves also offers ample resources for visitors to study the data themselves, inviting us to connect with a community fighting chronic illness and a society and system that questions their difficult realities living with LC. Ultimately, perhaps by connecting society’s fringes through honest conversations and heartfelt collaborations (as in this exhibition), the next wave we all experience may spare the torture, and rather be one of compassion and relief.

Raymundo Muñoz (he/him) is a Denver-based printmaker and photographer. He is the director/co-curator of Alto Gallery and board president of 501(c)(3) non-profit Birdseed Collective. Ray is guided by the principle that art is a bridge, and it connects us to ourselves and each other across time and space.