Ms. Destiny

Ms. Destiny

Center for Colorado Women's History

1310 Bannock Street, Denver, CO, 80204

April 4, 2025–March 27, 2026

Admission: $10

Review by Laura I. Miller

From “trad wives” to the “manosphere,” pushback against feminism has grown in recent years. A 2025 study by UN Women, the UN agency for gender equality, confirms that organized resistance to gender equality has gained momentum worldwide, citing the overturning of Roe v. Wade, the defunding of women’s ministries, and the killings of women’s rights activists in Mexico and Central America.

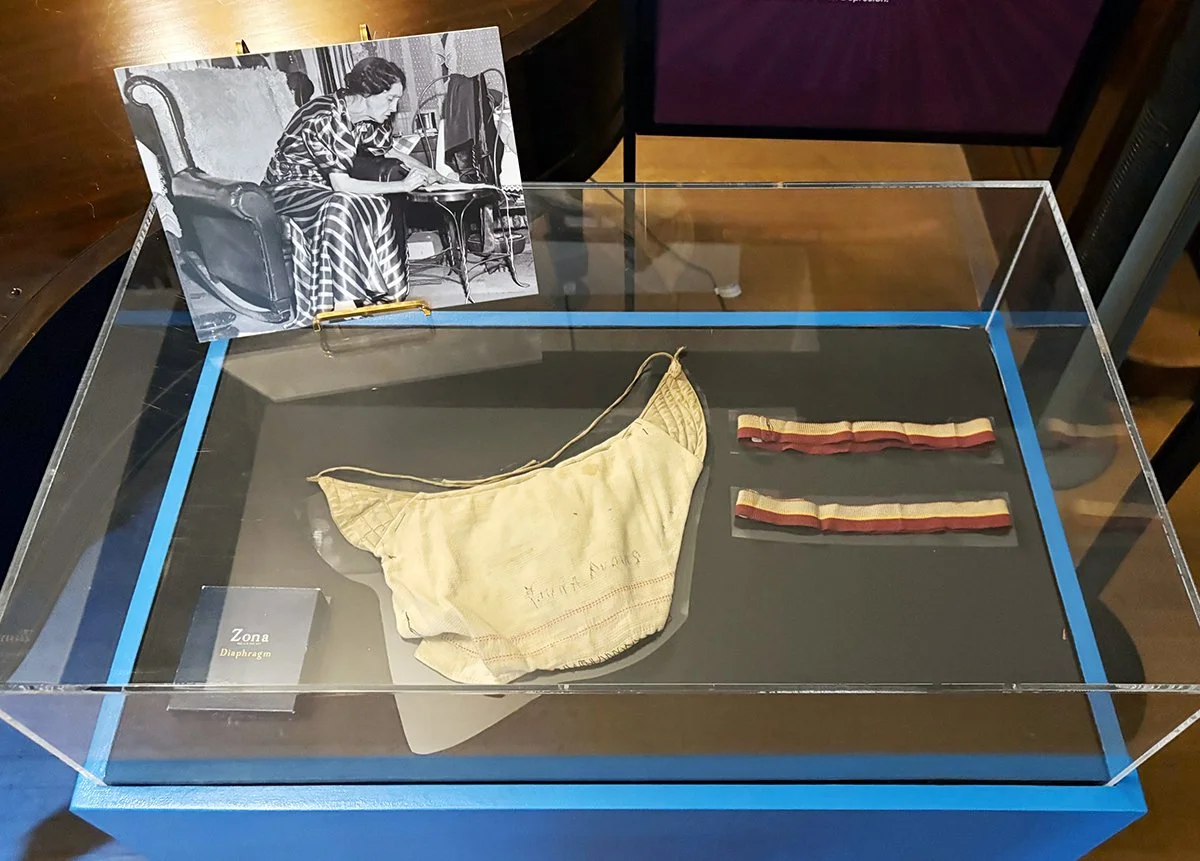

A view of the exhibition banners featuring the seven women included in the Ms. Destiny exhibition at the Center for Colorado Women’s History. Image by Laura I. Miller.

In this context, the Ms. Destiny exhibition at the Center for Colorado Women’s History, on view until March 27, 2026, is a powerful reminder of how far women’s rights have come—and a call to action, encouraging viewers to stand firm against the people and ideologies that threaten to erode our progress.

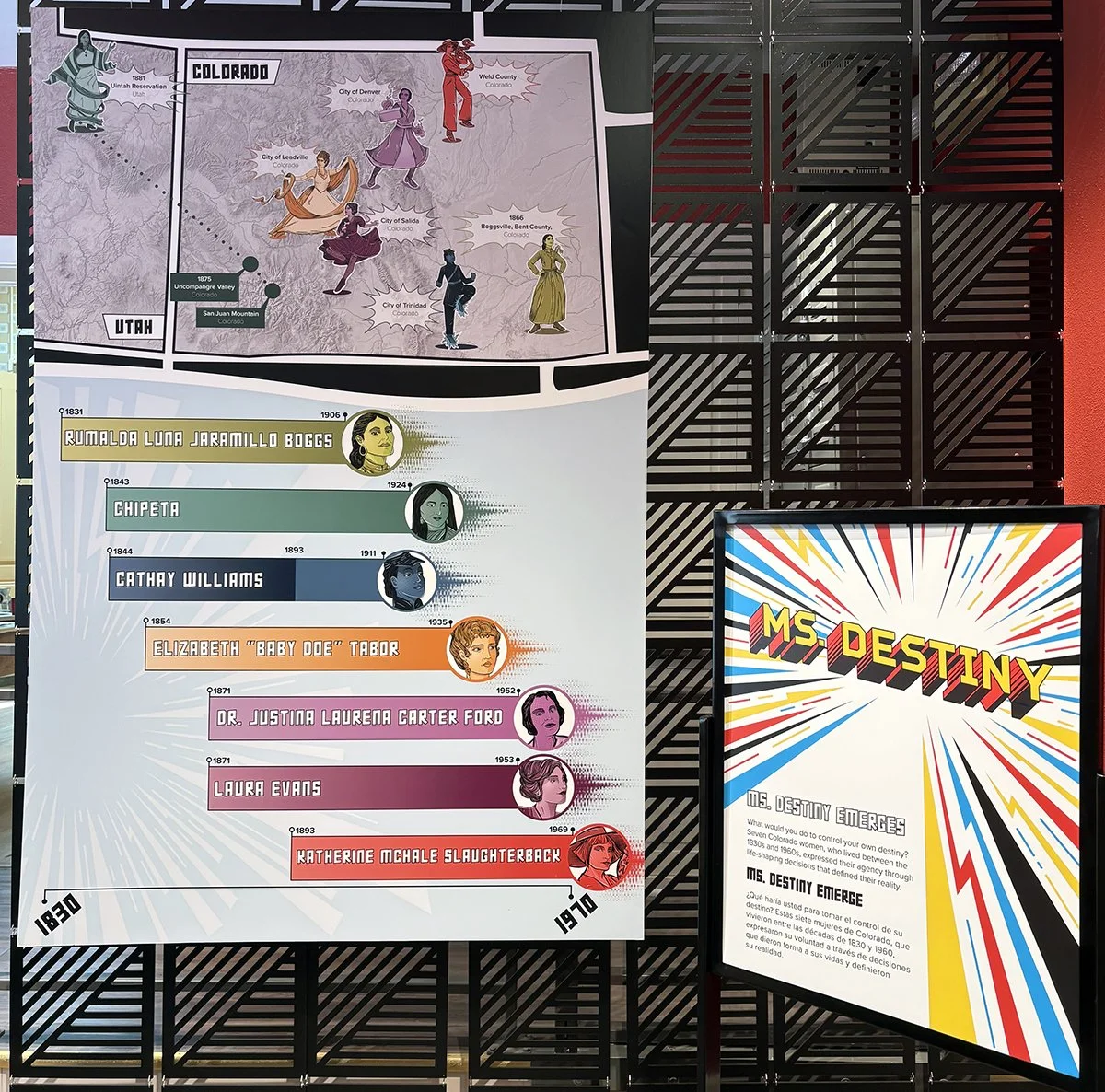

A view of the exhibition banner featuring the seven women, represented as comic book superheroes, included in the Ms. Destiny exhibition. Image by DARIA.

The exhibition takes the viewer on a journey through Colorado’s history, showcasing artifacts representing seven women who lived between 1831 and 1969. The banners and posters advertising Ms. Destiny borrow their style from superhero comics—the women, drawn with bold lines and colors, stand in active poses accentuated by the artifacts that represent them. The title of the exhibition, as well, plays on the Ms. Marvel characters and recent miniseries that are part of the Marvel Cinematic Universe.

An installation view of a portrait of Elizabeth Tabor from the History Colorado Collection in the Ms. Destiny exhibition. Image by Laura I. Miller.

While at first this approach may seem like a marketing technique meant to draw in visitors, as I went through the exhibition, its deeper meaning materialized. By reframing these women as superheroes, the curators elevate the everyday lives of women, shining a favorable spotlight on their radical actions, which, at the time, were viewed unkindly and often resulted in their treatment as social outcasts. Representing them as superhuman pays respect to the strength required to challenge the “cult of domesticity” that the vast majority of society adhered to at the time.

Defying gender norms

Born in 1871, Laura Evans arrived in Colorado during an era when sex work thrived in the shadows of boomtown economies. Yet despite its prevalence, the women who participated in this profession bore the weight of intense public scorn. Evans refused to live in the shadows, embracing her lifestyle and its community with open defiance and a charisma that unsettled codes of femininity.

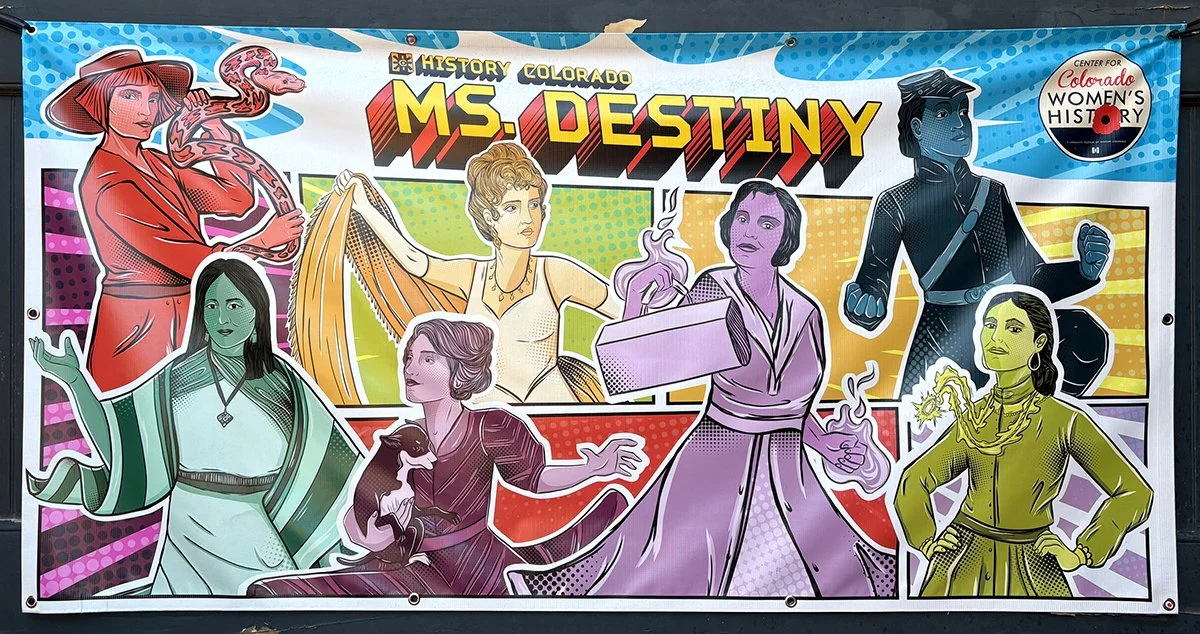

From left to right: Laura Evans’ diaphragm, rubber with cellophane wrapping, History Colorado Collection; Photograph of Laura Evans signing her bustle, 1950, History Colorado Collection; Laura Evans’ bustle pad, 1903, quilted cotton, History Colorado Collection; Laura Evans’ garter, synthetic elastic fabric, History Colorado Collection. Image by DARIA.

On display for Evans: a box containing a diaphragm rests beside a signed bustle pad and two faded garters. Even today, some viewers might be scandalized to see such intimate items in public. Starting the exhibition with these artifacts offers the viewer context for how women’s bodies were treated as commodities, capable of both empowerment and entrapment, and how contraceptives provided women more influence over their destinies.

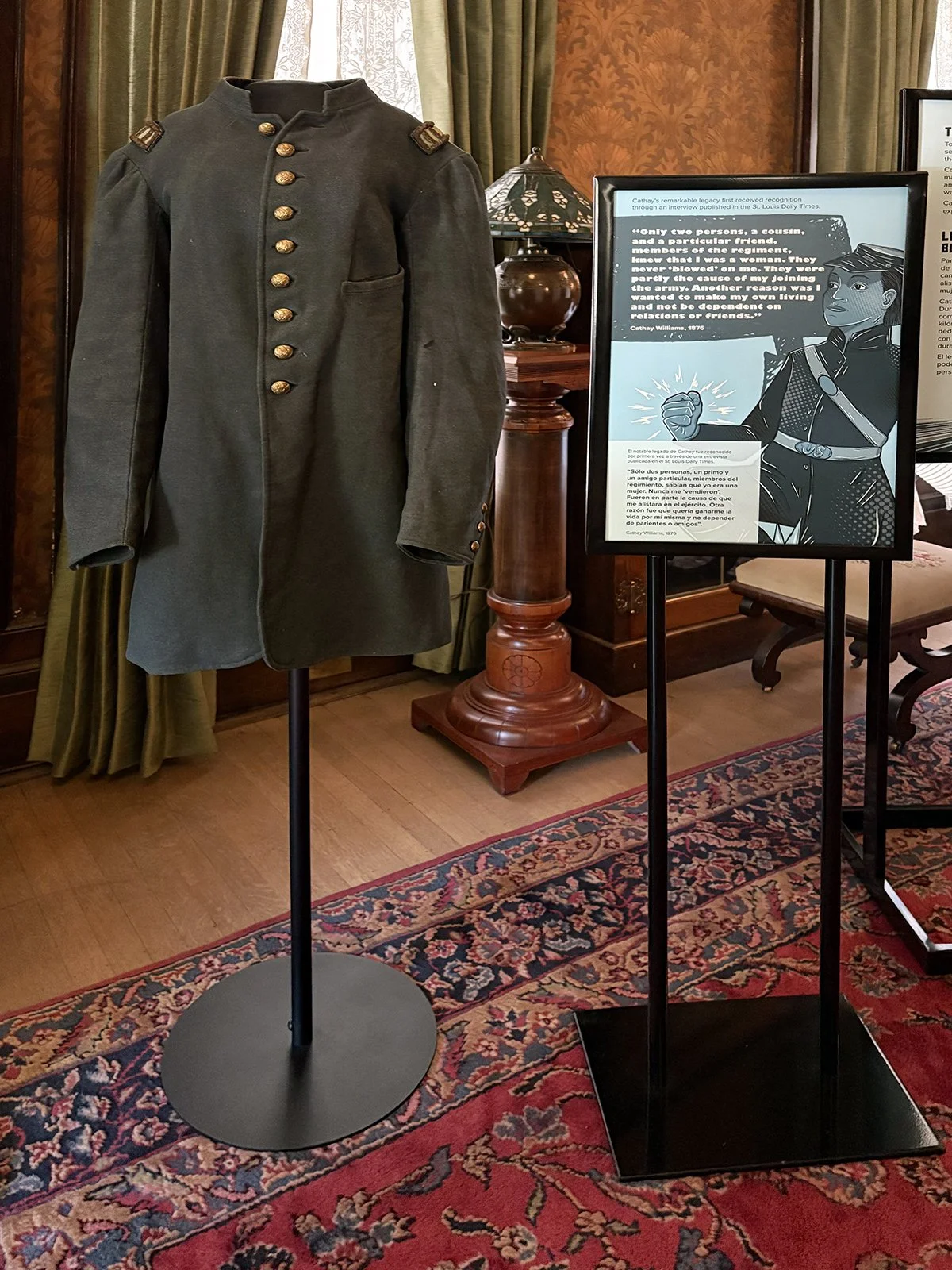

Civil War Uniform, 1864-1865, wool and silk with brass buttons, History Colorado Collection. Image by Laura I. Miller.

Born into slavery in Missouri, Cathay Williams was just seventeen when Union soldiers commandeered the plantation where she resided and conscripted her into forced labor. She served as a cook, nurse, and laundress until 1866, when emancipation opened the door to possibility. Williams concealed her gender by cutting her hair and adopting the name William Cathay and enlisted in the 38th U.S. Infantry. She became the only known female Buffalo Soldier. While there are many photographs of Laura Evans driving cars and dining with friends on display, no known photographs exist of Cathay Williams.

A photograph of a Buffalo Soldier Regiment, 1900, History Colorado Collection. Image by DARIA.

In their place the exhibition presents a reproduction of a 2023 painting by Gaia that imagines what Williams might have looked like, a 1900 photo of the Buffalo Soldier regiment—which was a segregated unit of African American soldiers in the U.S. Army—a Sista Soldier Dress from a traveling exhibition honoring the life of Williams, and a rifle similar to the one Williams might have carried.

Chloé Duplessis, Sista Soldier Dress, 2023, burlap, twine, and clothespins, courtesy of Duplessis Art. Image by DARIA.

Williams’s gender concealment lasted for two years, during which she endured illness, brutal marches, and the erosion of her physical health. Her identity was discovered during a routine medical examination, after which she was honorably discharged. “Only two persons, a cousin, and a particular friend, members of the regiment, knew that I was a woman,” said Williams in an 1876 interview published in the St. Louis Daily Times. “They never ‘blowed’ on me. … I wanted to make my own living and not be dependent on relatives or friends.”

Pillars of society

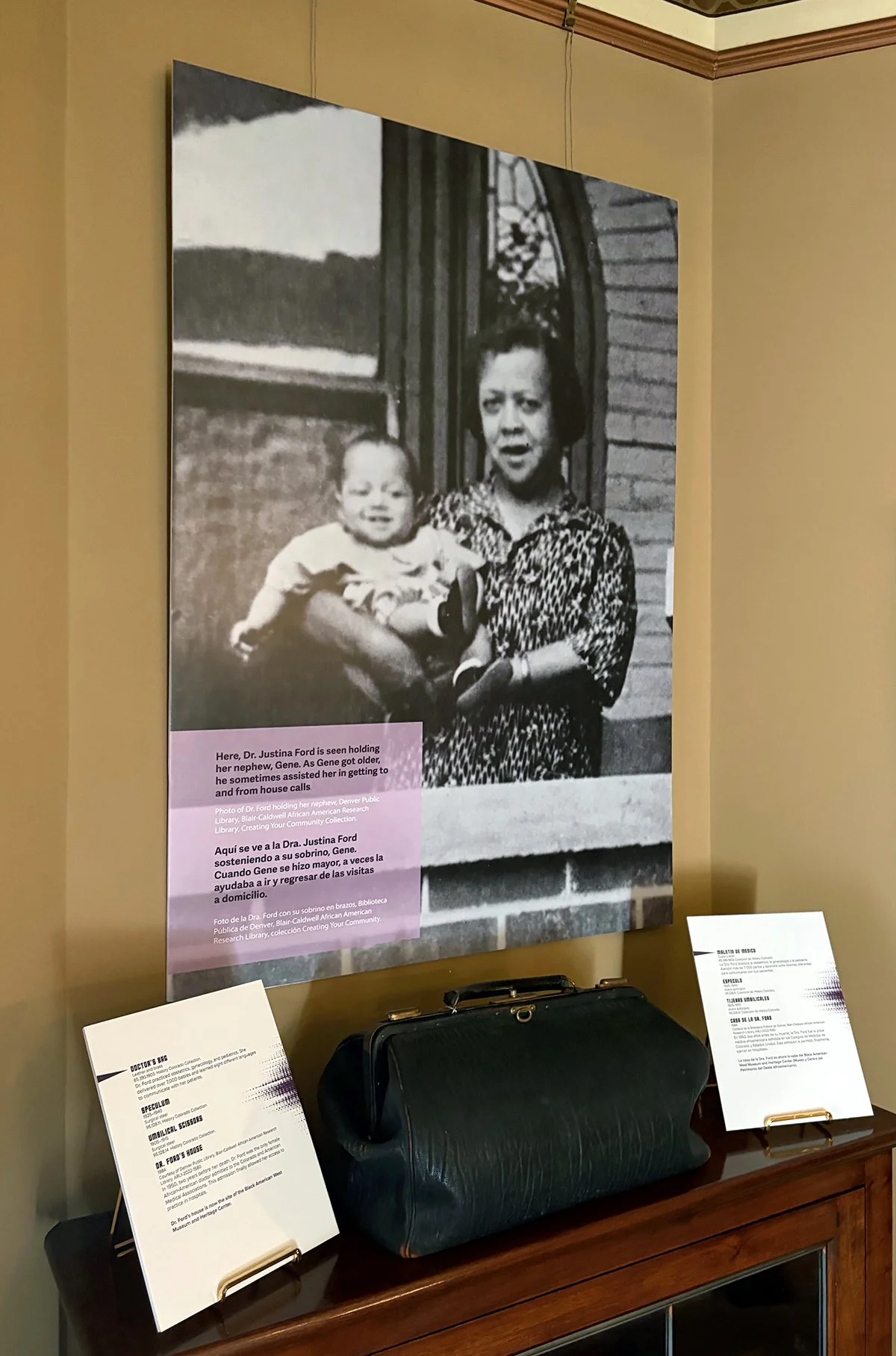

The daughter of formerly enslaved parents, Justina Ford earned her medical degree in 1899—a nearly unthinkable feat for a Black woman at the time. Ford entered the profession with “two strikes” against her, as one Colorado examiner put it: “First of all, you’re a lady, and second, you’re colored.” While not allowed to work in hospitals, Ford opened her own practice and made house calls, often treating those the formal medical system refused: Black families, immigrants, and the poor.

An installation view of Justina Ford’s doctor’s bag, leather and brass, and a photograph of Dr. Justina Ford with her nephew Gene, History Colorado Collection. Image by DARIA.

Artifacts on display for Ford include a large black leather doctor’s bag, a speculum, and umbilical scissors—instruments emblematic of the more than 7,000 children she’s said to have delivered over five decades. In a reproduction of a photograph that hangs above one of the museum’s many fireplaces, Ford holds her nephew Gene who, when he was older, assisted her with house calls.

Left: Speculum, 1925-1940, surgical steel, History Colorado Collection; Right: Photograph of Dr. Ford’s House, 1984, courtesy of Denver Public Library, Blair-Caldwell African-American Research Library, History Colorado Collection. Image by DARIA.

“I fought like a tiger against those things…,” Ford told a reporter for the Negro Digest about overcoming the barriers to becoming a doctor and running her own practice. “Folks make an appointment, and I wait for them to come or go to see them, and whatever color they turn up, that’s the color I take them.”

Next in the exhibition is Rumalda Luna Jaramillo Boggs, who was born into a prominent Hispano family in northern New Mexico and inherited a vast land grant in southern Colorado passed down from her godfather, Cornelio Vigil. At fifteen, she married Thomas Boggs, a union that reflected the cultural and political transitions reshaping the region.

An installation view of the portrait of Rumalda Boggs, date unknown, courtesy of Boggs Historical Society. Image by Laura I. Miller.

Though few photos remain of Jaramillo Boggs, the stoic portrait on display, showing her in a long-sleeved black dress and earrings that resemble arrowheads, belies her reputation for warmth and hospitality. She was known for hosting Taos-style dances, cooking for guests, and welcoming people into her home. A saddle on display speaks to the mobility and endurance of Hispano women across the Southwest, and the gloves of her aunt, Josefa Jaramillo, suggest a lineage of domestic grace intertwined with social resilience.

Romanticized survivors

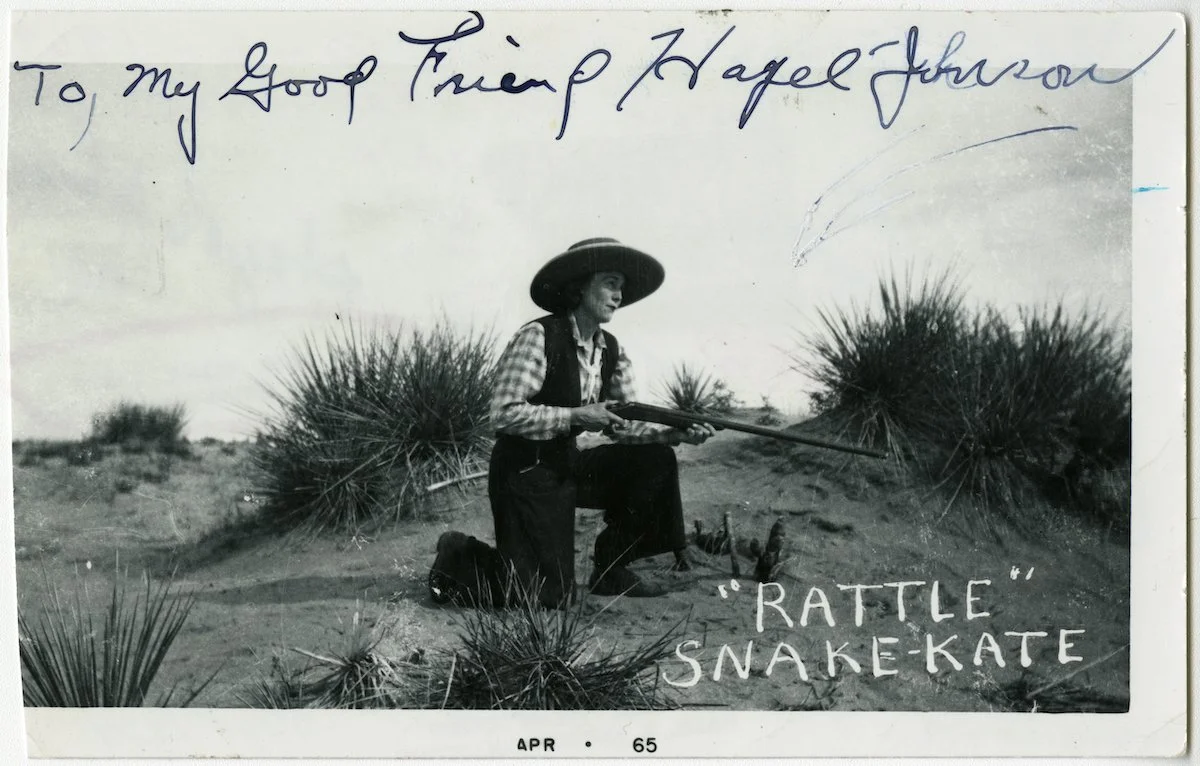

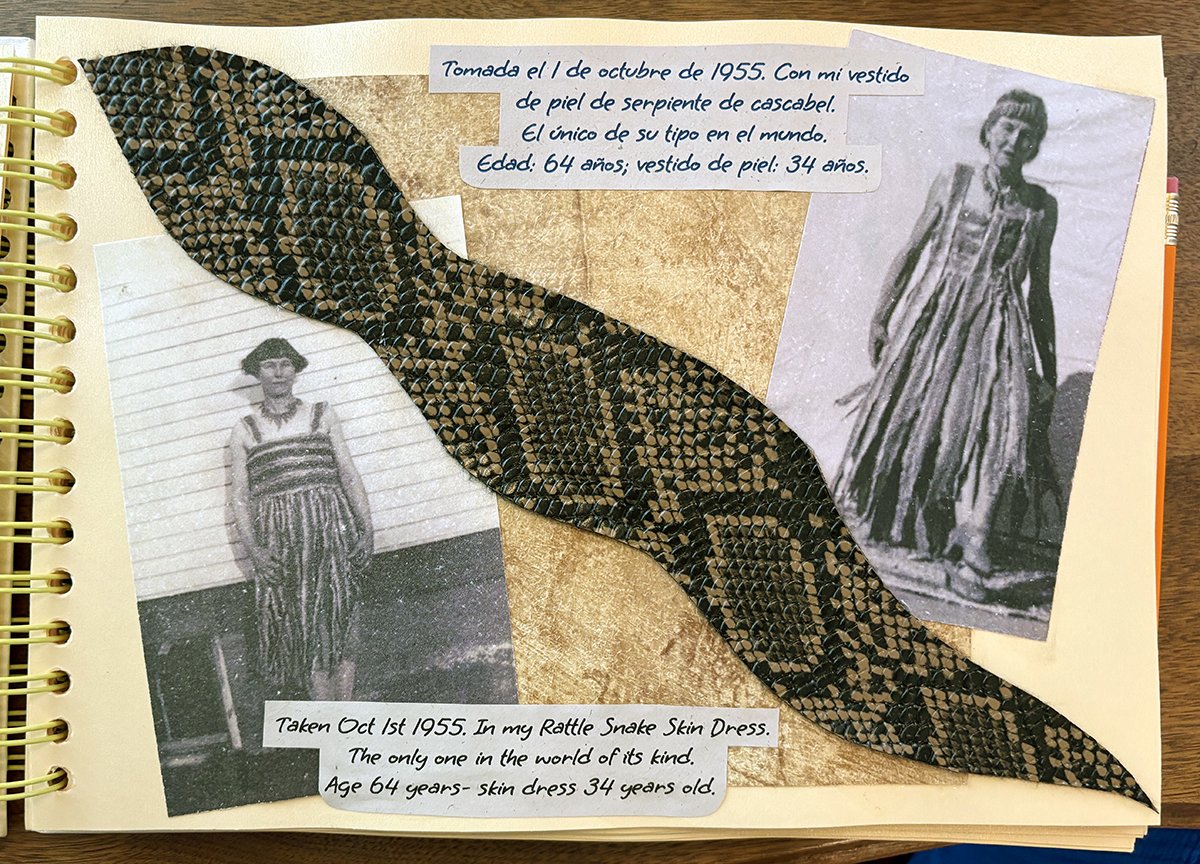

On the plains of rural Colorado in the early twentieth century, Katherine Slaughterback fashioned a life from hardship and spectacle. She farmed, shot rifles, bootlegged, practiced taxidermy, and made a living peddling snake meat and souvenirs for tourists. Her story, however, turned into legend in 1925 when she and her son encountered a migrating den of approximately 140 rattlesnakes.

A photograph of Katherine Slaughterback/Rattlesnake Kate, 1965. Image courtesy of the Center for Colorado Women's History.

Armed with a short club, she fought them off for more than two hours, whirling and striking until they could escape, a seemingly tall tale that was later confirmed by local reporters. That moment transformed her into an international sensation. She became known as “Rattlesnake Kate,” a moniker she wore with pride, even crafting a dress from the skins that she wore into her sixties.

Rattlesnake Kate’s beaded belt, 1930s, beaded leather belt with brass buckle, courtesy of Greeley History Museum. Image by Laura I. Miller.

Supposedly married six times, Slaughterback defied the domestic roles expected of her—“a good sweetheart but a terrible wife,” as one husband put it—and cultivated a persona of frontier resilience. Her scrapbook and belt, beaded and brass-buckled, sit alongside a string of rattlesnake tails—emblems of a life lived with bravado and survivalist skill. A bronco rider who competed in the National Western Stock Show in her seventies, Rattlesnake Kate built her own mythology in a world that rarely made space for women like her.

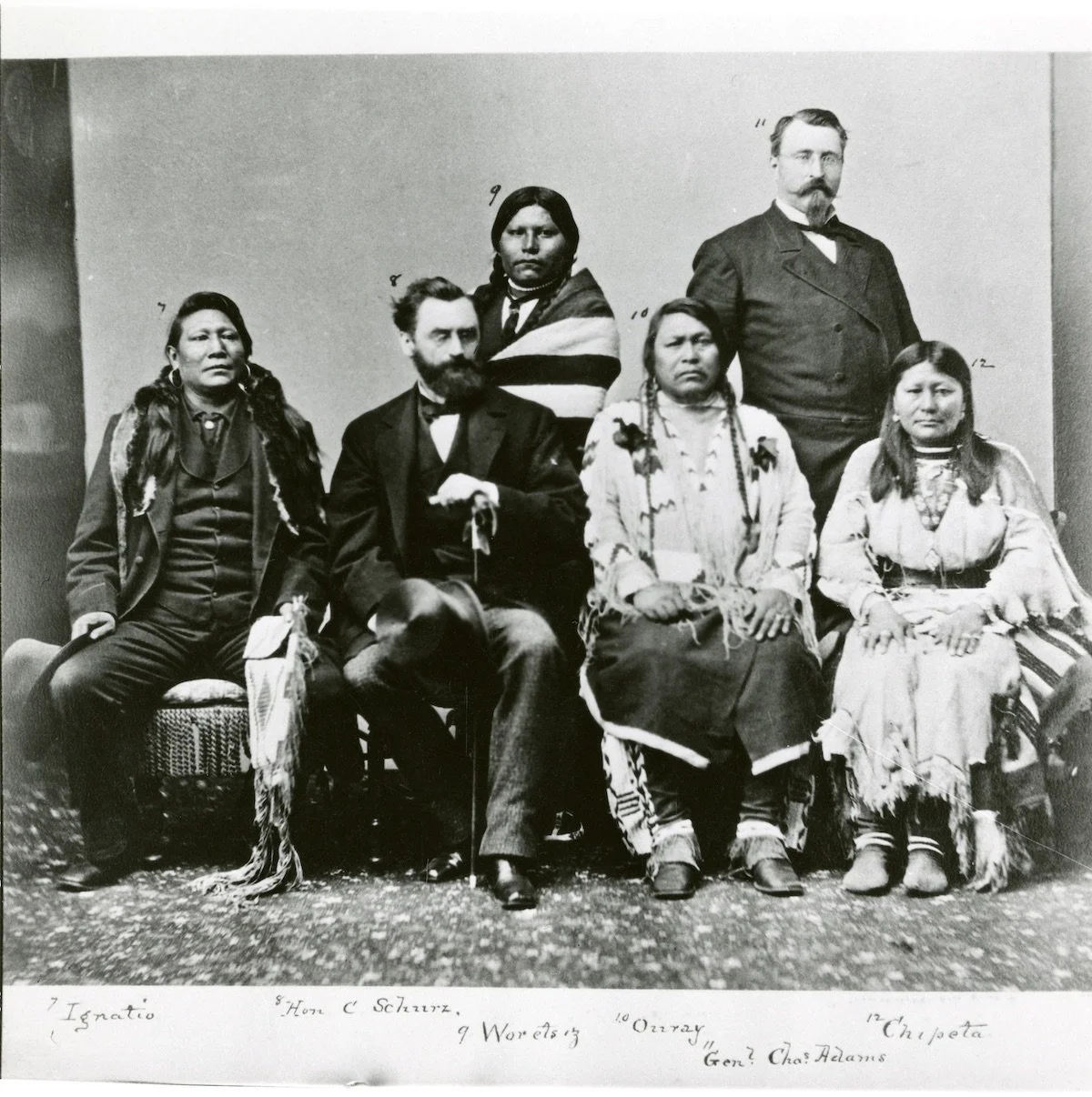

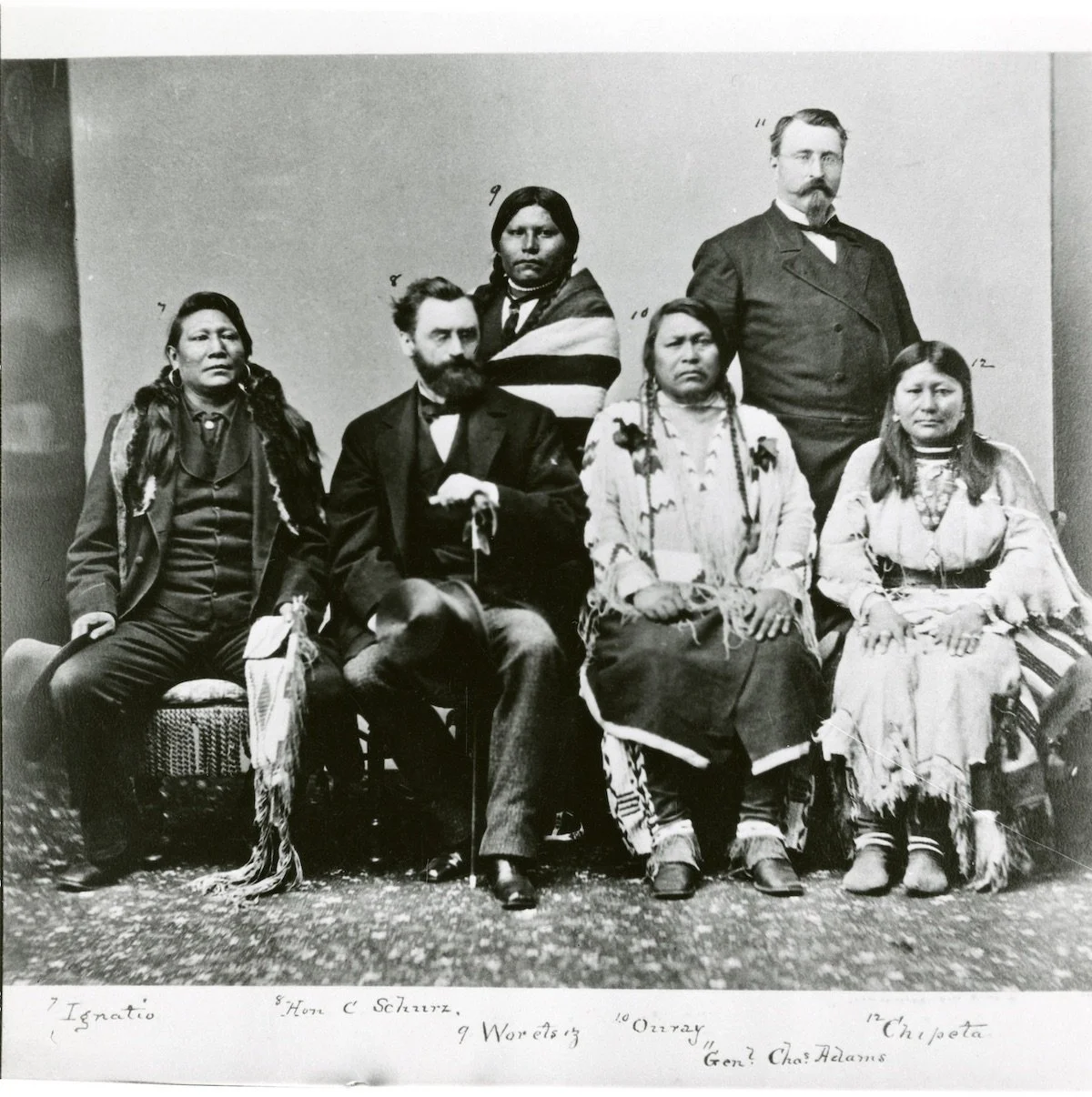

Photograph of Chipeta in Ute Treaty Delegation, 1874, History Colorado Collection. Image courtesy of the Center for Colorado Women's History.

Born fifty years before Rattlesnake Kate, another woman, Chipeta, became a crucial figure in reframing views around women. Married to Chief Ouray of the Ute tribe in 1859, Chipeta joined the fraught negotiations between the Ute peoples and the U.S. government. As the only woman in the 1874 Ute Treaty Delegation to Washington, D.C., Chipeta occupied a space few Indigenous women were permitted to enter: one of diplomacy, mediation, and political visibility. For nearly two decades, she advocated for peace and treaty compliance, amid escalating U.S. aggression, including the forced removal of the Ute peoples from Colorado lands.

A photograph of Chipeta with a blanket draped over her shoulders. Image by DARIA.

A defender of Ute women’s autonomy in a world bent on eroding it, Chipeta taught leatherworking and beading to younger generations. Yet, the press still romanticized her as a “Ute Queen” while degrading her with racist and sexualized depictions. After her death in 1924, her body’s return to Colorado was celebrated by the media without a reckoning of the exile that had preceded it.

From opulence to destitution

Among the artifacts in Ms. Destiny, none dazzles more than Elizabeth “Baby Doe” Tabor’s wedding gown, made of creamy silk damask with seven feet of train and layered ruffles and a lace-trimmed hem. Rumored to have cost $7,000 in 1883, which translates to nearly a quarter of a million dollars today, it embodied the height of Gilded Age opulence. It also came to represent the precarious fantasy of American ascent.

Elizabeth Tabor’s wedding dress, 1883, silk damask and cotton lace, History Colorado Collection. Image by DARIA.

Born into a financially unstable Midwestern family in 1854, Tabor first married Harvey Doe when she was 23 years old and followed him to Colorado’s mining camps. His drinking, gambling, and frequent brothel visits led her to divorce him—a rare act for a woman of the time. Her next marriage, to silver magnate Horace Tabor, elevated her to national infamy. Twenty-five years his junior, Elizabeth was mocked as vain and manipulative. Yet, the letters she wrote to Horace, and her decades-long widowhood, offer proof of her devotion in the face of public ridicule.

A photograph of Elizabeth Tabor, History Colorado Collection. Image courtesy of the Center for Colorado Women's History.

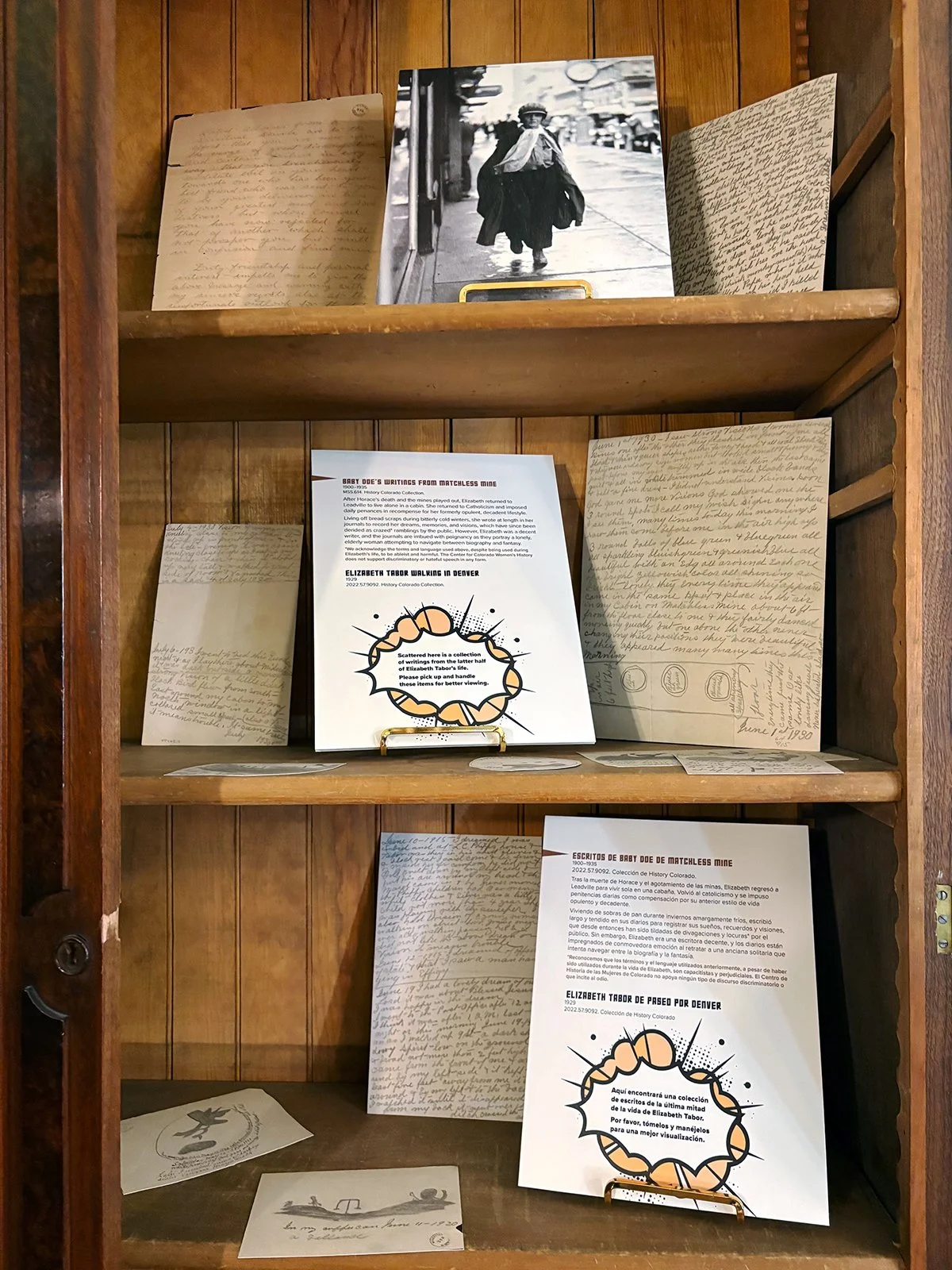

In Central City, Elizabeth Tabor mined alongside men, wearing trousers and supervising labor—possibly the first woman to do so in the region. Miners dubbed her “Baby Doe” for her large eyes and gentle demeanor, though it’s unclear whether she embraced the nickname. After Horace’s death and the collapse of their fortune, Elizabeth returned alone to Leadville. There, she lived a life of scarcity and penance, writing feverishly in journals, many reproduced pages of which are on display. While the press turned her into a parable of madness, her writings have since become an inspiration for many authors, researchers, and biographers.

Elizabeth Tabor’s writings from Matchless Mine, 1900-1935, History Colorado Collection; Photograph of Elizabeth Tabor walking in Denver, 1929, History Colorado Collection. Image by DARIA.

Tabor held on to her wedding gown—even as she starved, subsisting on only breadcrumbs, eventually freezing to death in her cabin in 1935—an act that earned her the nickname of “the madwoman in the cabin.” Yet, the dress remains to tell her story, a heartbreaking reminder of the cruelty of society and the empty promise that marriage would provide the security and community that these women deserved.

A view of Rattlesnake Kate’s scrapbook. Image by Laura I. Miller.

While walking through the Victorian mansion that houses the Center for Colorado Women’s History, I was struck by how much I felt the presence of these seven women, despite the scarceness of artifacts that remain. The venue enlivens their stories, while the exhibits highlight how much our society has changed. At a time when we’re plagued by overconsumption and vast photographic evidence of our existences on social media, it seems impossible that so little endured from these important women’s lives: not a single photograph of Cathay Williams nor a scrap of clothing belonging to Rumalda Luna Jaramillo Boggs. Their influence persists, however, perhaps serving as a model for and reminder of how to live meaningful lives that don’t just mirror inequities, but alter the course of the future.

Laura I. Miller (she/her) is a Denver-based writer and editor. Her articles, reviews, and short stories appear widely. She received an MFA in creative writing from the University of Arizona.