Jaime Carrejo

Artist Profile: Jaime Carrejo

On the Poetics of Points, Material, and Time

by Felicity Wong

Jaime Carrejo has been on a bit of a hiatus. When I first perused the portfolio on his website and scrolled through his Instagram account, I noticed that he last exhibited his art in 2021. But in a recent conversation with him, he revealed just how busy he still is. The week prior to our call, he had traveled to a conference in Washington, D.C. that took him several years to organize. He also currently teaches a wide range of courses on ceramics, sculpture, welding, and time-based media at the Rocky Mountain College of Art and Design, and serves on the boards of the Contemporary Art Alliance for the Denver Art Museum and Tilt West Denver, as well as the Public Art Committee in Denver.

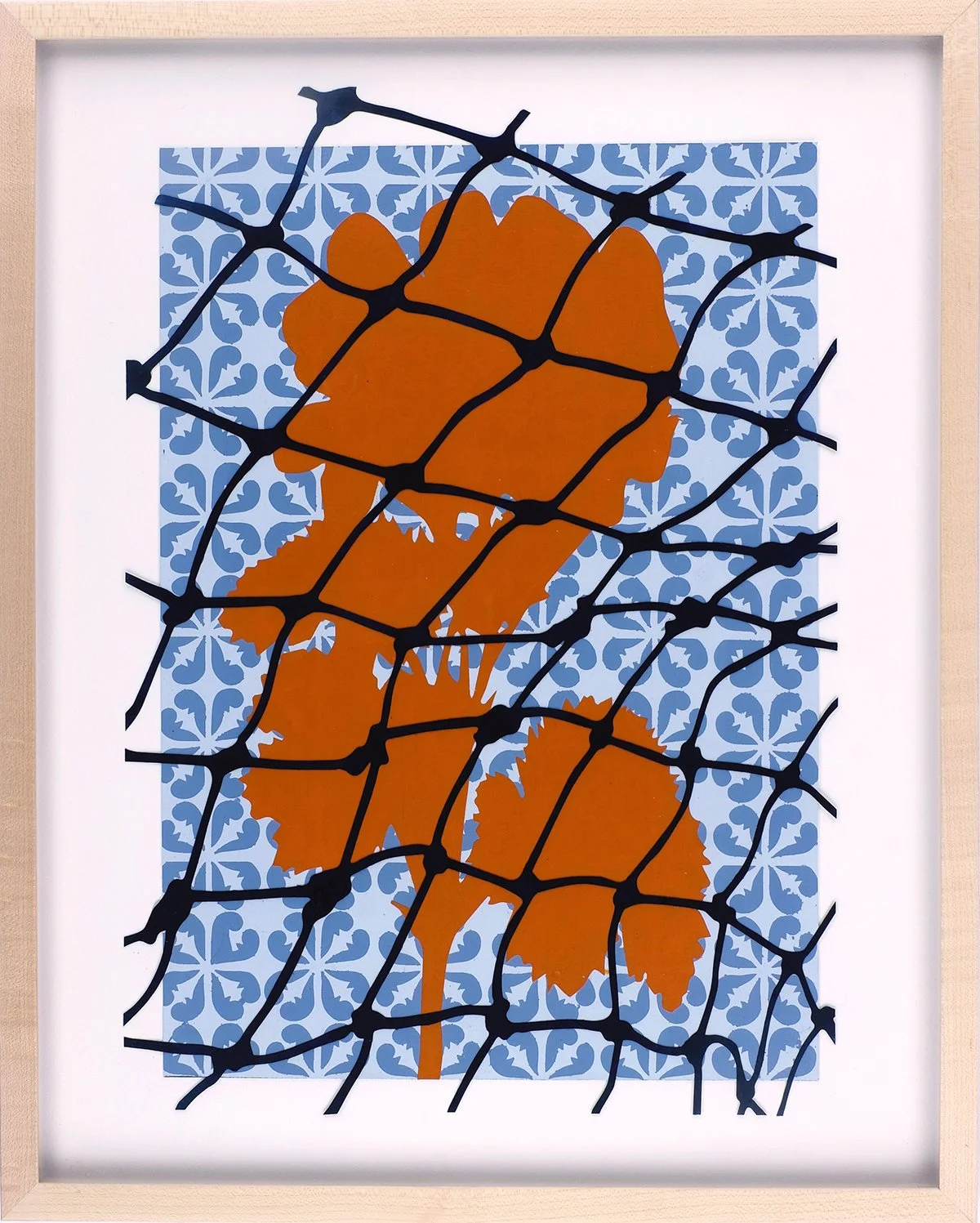

Jaime Carrejo, a breeze and a storm no. 2, 2023, synthetic polymer on paper. Image courtesy of the artist.

The many hats he wears intertwine. For Carrejo, who received his BFA from the University of Texas El Paso in 2002 and an MFA from the University of South Florida in 2007, the processes of artmaking and teaching are similar. The artist and arts educator is charged with the same duty to ask difficult questions about change. What does change look like? And how can one enact it via modes of artistic expression?

Jaime Carrejo, Flora No. 4, 2020, synthetic polymer on wood panel, 40.5 x 60 x 1.25 inches. Image by Wes Magyar, courtesy of Jaime Carrejo.

Carrejo’s work is grounded in considerations of individuals’ relationships to community within broad—and possibly even metaphysical—contexts. In the studio, he explores his personal relationships with a body of research. In the classroom, he focuses on cultivating relationships among faculty members and students, giving them the space to probe the questions that will allow them to achieve their goals. Within the wider community of Denver, the United States, and the world, Carrejo’s community-oriented practice poses a new question of relationship: what does it mean to belong to a larger whole?

Jaime Carrejo, installation view of One Way Mirror at the Denver Art Museum, 2017, HD video, audio, steel, acrylic, marine painting, and tinting. Image by Wes Magyar, courtesy of Jaime Carrejo.

In One Way Mirror (2017), Carrejo investigates belonging and, more specifically, a temporary sense of belonging, by projecting footage of landscapes from the United States and Mexico onto tilted walls situated opposite to one another. He then places a paneled mirror between the two walls to warp conceptions of space and place for the viewer walking through the installation. But this footage does not only display blue skies and lush hills—it also features unique fence constructions. X's layer on top of the Mexican sunrise on one side, while red bars reminiscent of the stripes on the American flag run across a film of the sun setting in the United States on the other.

Jaime Carrejo, installation view of One Way Mirror at the Denver Art Museum, 2017, HD video, audio, steel, acrylic, marine painting, and tinting. Image by Wes Magyar, courtesy of Jaime Carrejo.

Carrejo’s projects ask questions that ultimately challenge viewers to contextualize them within their personal lives. He recounts a story about a student at the University of Colorado Denver who was particularly moved after seeing One Way Mirror in the Mi Tierra: Contemporary Artists Explore Space exhibition at the Denver Art Museum, having never before seen people of Latine descent like himself represented in museums.

An older German visitor—who witnessed the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989—marveled at One Way Mirror’s ability to capture the feeling of skies opening up and closing. Carrejo likes to call the balance between the collective and individual narratives in the interpretation of his work “poetic points.” It is his hope that these “poetic points” spur personal calls to action and inspire people to give each other space to speak their minds without opposition.

Jaime Carrejo, Pa’lante, 2021, digital print on nylon, 72 x 120 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

Pa’lante (2021) is a more recent example in Carrejo’s oeuvre that illustrates an embrace of his philosophy of a “poetic point.” He created Pa’lante—a Spanish contraction that roughly translates to “onward”—for the Momentary Flag Project. Displayed in the contemporary satellite space of Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas, the flag combines layers depicting immigration patterns from Latin America as reported by the Pew Research Center, silhouettes of a broken chain fence, references to time in the form of a quartered circle, and an olive branch.

Jaime Carrejo, close-up of Pa’lante, 2021, digital print on nylon, 72 x 120 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

Carrejo abstracts the images on these layers by stacking them on top of each other within the square footage of the flag and rendering them in shades of bright blue and pink. He effectively establishes the foundations for solidarity—for moving onward—by sparking conversations among immigrant communities in Arkansas and broader publics about what those symbols on the flag might mean individually and together.

Jaime Carrejo, Frontera No. 10, 2019, synthetic polymer on paper, 15 x 19 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

The chain-link motif recurs in Carrejo’s projects, but it is perhaps the most prominent throughout his Frontera (2019) and Flora (2020) series, commissioned by the Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA) Denver for their Octopus initiative. In both series, Carrejo superimposes images of barbed wire fences and thorns upon multiple layers of patterns and silhouettes of blooming plants from the southern borders of the United States, Europe, and Asia. The simultaneity of the harsh, uniform barriers in the prints’ top layer and the colorful life depicted in the bottom highlights the plants’ unnatural constriction and isolation.

Jaime Carrejo, Frontera No. 1, 2019, synthetic polymer on paper, 15 x 19 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

Informed by the queer Chicana scholar Gloria Anzaldúa, who theorizes the border as an open wound that does not heal, Carrejo questions here the fraught relationship between human-made barriers—which can manifest in a physical fence or, more metaphorically, as tools or language—and natural landscapes. Each plant within the landscape of the print represents a person who needs care—much like house plants, Carrejo notes, which are native to and meant to flourish in locations that have been capitalized on for human gain.

Jaime Carrejo, Frontera No. 18, 2019, synthetic polymer on paper, 15 x 19 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

Instead, house plants are brought into foreign environments—the living spaces of our homes—and confined to a life inside of a pot. Of course, in classic “poetic point” fashion, the boundaries in Flora and Frontera can extend beyond discourses on immigration to more general ones about the spaces where people are ostracized because of their identities.

Jaime Carrejo, installation view of Waiting at the Museum of Contemporary Art Denver, 2021, wallpaper, plywood, synthetic polymer on wood panel, faux house plants, Arduino kinetic motors, home furniture, vinyl, and steel. Image by Wes Magyar, courtesy of Jaime Carrejo.

Waiting (2021) further develops Carrejo’s interest in the politics of the house plant. Inspired by mid-century modern waiting rooms, Carrejo stages a domestic living space in this installation: two chairs positioned on slanted wooden platforms are surrounded by quarter wedge-shaped paintings of houseplants. Behind these paintings are walls with plant patterns in red, pink, and blue hues. Scattered around the room are large, leafy house plants hanging from the ceiling.

Jaime Carrejo, installation view of Waiting at the Museum of Contemporary Art Denver, 2021, wallpaper, plywood, synthetic polymer on wood panel, faux house plants, Arduino kinetic motors, home furniture, vinyl, and steel. Image by Wes Magyar, courtesy of Jaime Carrejo.

Waiting pays homage to house plants—one of the parts of Carrejo’s home that he realized he neglected during the first peak of the coronavirus pandemic in 2020 when he, along with the rest of the world, transitioned to a life in lockdown. He describes “pandemic time” as a point of anxiety, filled with a collective waiting for change and “normalcy.” In Waiting, Carrejo paints the silhouettes of the house plants against a dark blue background with repeated sets of bright red quarters that together form a clock shape—almost like the plants can tell time themselves. This act of painting his house plants’ portraits over such an intimate and surreal period of time was not just one borne from anxiety, but also from love and care.

Jaime Carrejo, Today, Tomorrow, 2019, iron infused paint and synthetic polymer on paper, 19 x 15 x .75 inches each. Image courtesy of the artist.

Although Carrejo’s several years-long hiatus may be coming to an end, he reflects often on its value. Since exhibiting Pa’lante, he has spent cherished time with his family—especially his adopted son—and reevaluated the direction of his practice. In many of his ongoing projects, he returns to ceramics, a medium he is drawn to because of the history of its materiality, as well as the time-based nature of making with clay. Carrejo has historically employed a number of mediums—from printmaking to sculpture to installation—in his work. Yet he has never felt tied to one specifically, instead articulating what he calls an interest in the “poetics of material” and the multiplicity of avenues through which meaning can be constructed.

Jaime Carrejo, a breeze and a storm no. 1, 2023, synthetic polymer on paper. Image courtesy of the artist.

During his hiatus, Carrejo also encountered texts that have both directly and indirectly shaped his art. These include Ross Gay’s Inciting Joy, which unpacks the profound entanglements between experiences of joy and pain, sometimes in relation to gardening and, more recently, bell hook’s Belonging, where she writes about segregation and the tension between closed and open spaces. To supplement this, Carrejo has also read Mary Oliver’s prose and poetry, which he enjoys splitting up into small chunks that can be digested over long periods of time.

Jaime Carrejo, Flora No. 5, 2020, synthetic polymer on wood panel, 40.5 x 60 x 1.25 inches. Image by Wes Magyar, courtesy of Jaime Carrejo.

In Upstream, Oliver writes, “there is no other way work of artistic worth can be done. And the occasional success, to the striver, is worth everything. The most regretful people on earth are those who felt the call to creative work, who felt their own creative power restive and uprising, and gave it neither power nor time.” Certainly, Carrejo has given his due time. Taking time off has allowed him to think about time—how we mark, spend, value, and negotiate with it—in his upcoming work. After all, Carrejo would know, better than anyone else, how the gift of time can lead to the multiplication of its abundance.

Felicity Wong’s (she/her) research and writing focuses on contemporary fiber arts, everyday objects associated with Asia and its diasporas, and the relationship between fashion, decay, and language. She received her BA in English from the University of Notre Dame and currently studies contemporary Art History at the University of Colorado Boulder.