Where You Really Are, And Where I Really Am

Olive Moya: Where You Really Are, And Where I Really Am

Bell Projects

2822 E. 17th Avenue, Denver, CO 80206

August 16–September 28, 2025

Admission: free

Review by Nina Peterson

To noodle is to play around, to improvise, and to embrace the fortuitousness that results from the process of creation. The artist Olive Moya has developed a visual language of “noodles”—a term she uses to describe the undulating, colorful strands that wiggle and twist in her artworks. [1] Moya’s solo exhibition Where You Are, And Where I Really Am at Bell Projects makes the case for a playful, iterative approach to enacting and understanding identity.

An installation view of Olive Moya’s exhibition Where You Really Are, And Where I Really Am at Bell Projects. Image by Nina Peterson.

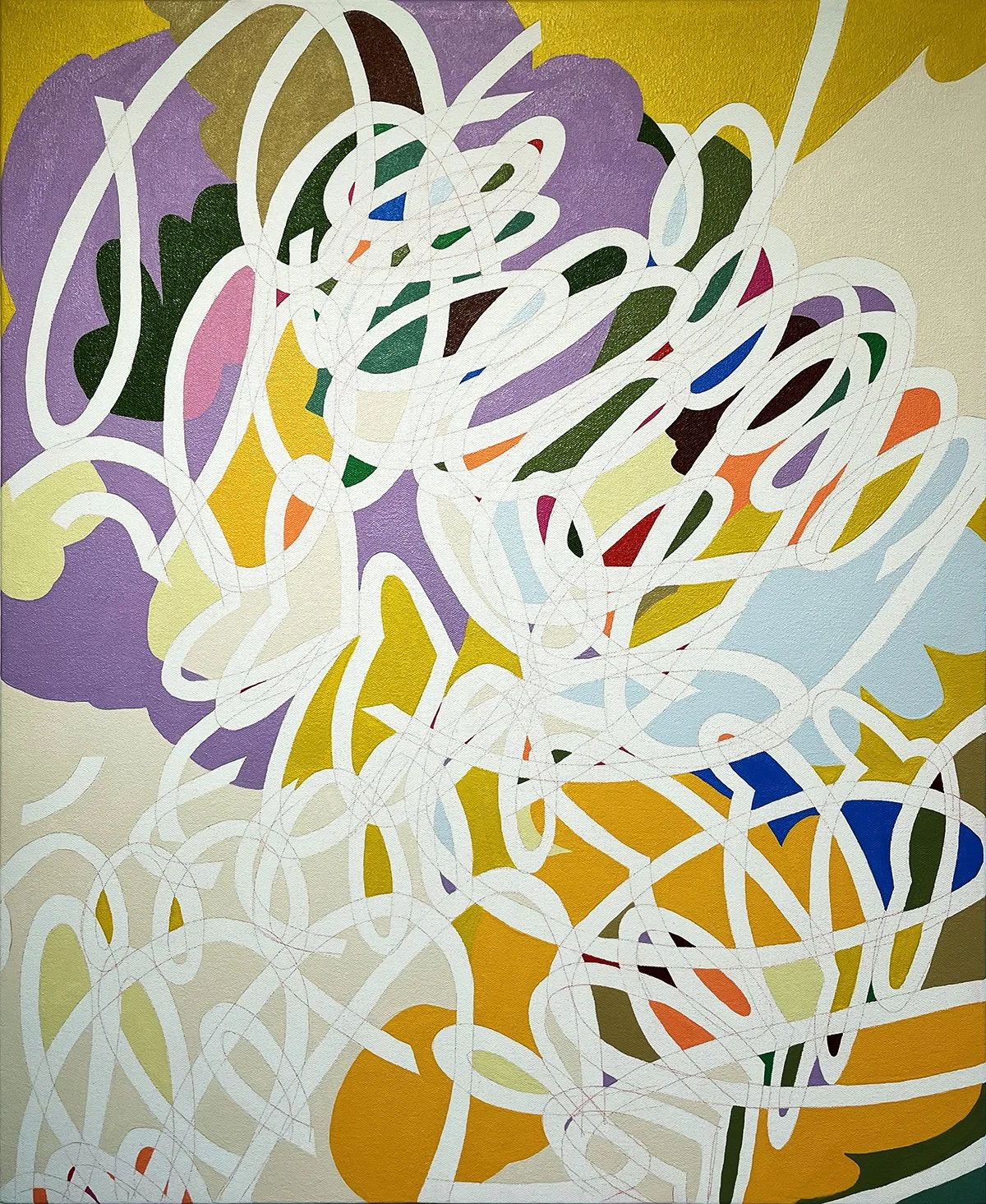

The exhibition includes mixed media works on canvas, paper, and mylar. According to curator and gallerist Lindsey Bell’s exhibition guide, Where You Are, And Where I Really Am “navigates the intimate experience of collecting, abandoning, masking, and revealing identities and thought processes—whether constructed or inherited over time.” [2]

Olive Moya, Dreamers Never Learn, 2025, mixed media on paper. Image by Nina Peterson.

Olive Moya, Dreamers Never Learn (detail), 2025, mixed media on paper. Image by Nina Peterson.

Artistic processes of revealing and masking are apparent in Dreamers Never Learn, a mash-up of traced spirals, expressively applied paint, and delicate pen drawings. In the upper left corner of this work on paper, curly cues merge in and out of thickly applied lavender, cerulean, and lime acrylic paint. In the middle left of the composition, a layer of translucent yellow veils the scribbles and squiggles beneath. At nearly the center of the composition, a sketched hand emerges from a field of modulated green paint and pen-drawn noodles.

Olive Moya, Dreamers Never Learn (detail), 2025, mixed media on paper. Image by Nina Peterson.

Describing her background in handlettering, Moya notes that the noodles emerged from the same process, and each noodle is thus “a letter but not a letter.” [3] This is important because language shapes identity. Letters, as units of written language, are communicable components of how individuals claim identities and how society thrusts them upon us. The nebulous status of Moya’s noodles—they both are and are not characters for communication—marks their use as tools for play even as it points to systems of social inscription. [4]

Olive Moya, I Don't Relate To My Peers, 2024, acrylic on canvas. Image by Nina Peterson.

Moya’s noodles variously call to mind playground slides, slinkies and springs, or (when blocked in with paint) clouds, petals, or abstract glimpses of cartoon characters. These shapes do not coalesce into anything concretely legible. Rather they evoke daydreaming and scheming, and invite viewers to engage in imaginative associations without prescribing or confessing any singular aspect of identity or identification.

Olive Moya, Et Cetera, Et Cetera, 2025, mixed media on paper. Image by Nina Peterson.

If these paintings reveal an aspect of identity, the artist’s or anyone else’s, then they are not compelled disclosures or an invasion of privacy perpetrated by sneaking a peek at someone’s diary. Rather, these works are burlesques that resist interpretive finality or clarity. This kind of performed divulgence prompts a mischievous toggle between the works’ energetic, vibrant forms and the viewer’s (perhaps perplexed) apprehension of them.

Olive Moya, And I’d Just Laugh, And I’d Feel Silly #1 and #2, 2025, mixed media on paper. Image by Nina Peterson.

The exhibition guide describes Moya’s process of making as “a visual game of telephone,” and I’d say this is an apt way to describe the viewing experience as well. [5] As kids know well, the fun of telephone derives not from the accuracy of repeating a phrase exactly as it is originally spoken but from the absurd results of a chain reaction of multiple whisper-coaxed mishearings and deliberately distorted retellings.

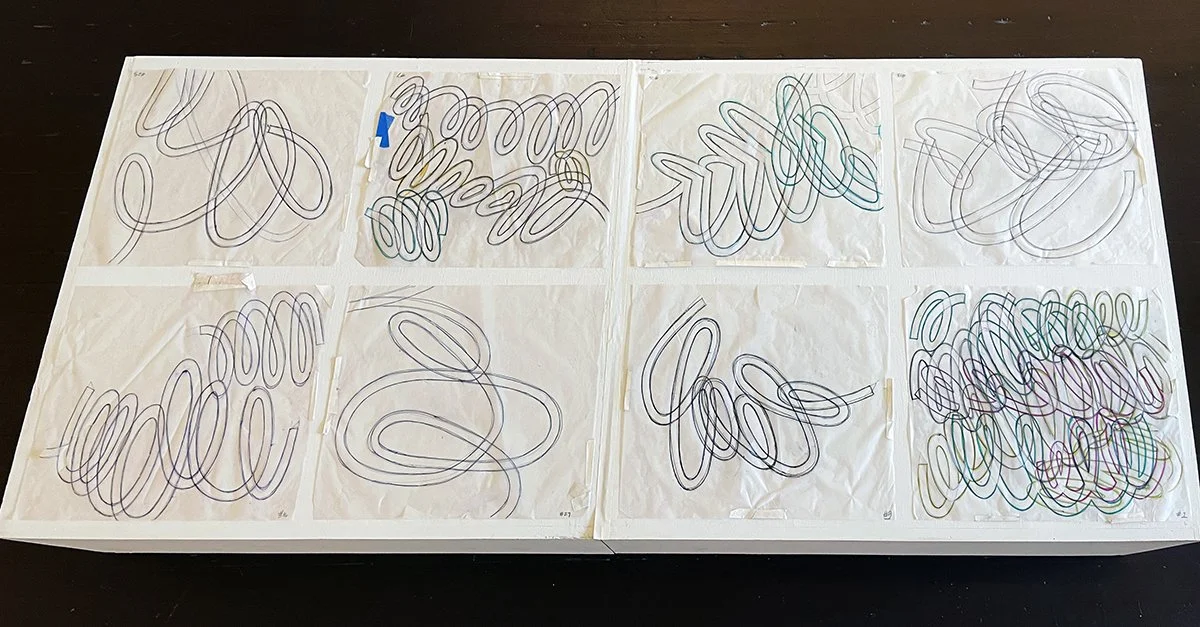

A view of tracing papers on a plinth in Olive Moya’s exhibitin Where You Really Are, And Where I Really Am at Bell Projects. Image by Nina Peterson.

A detail view of a tracing paper design in Where You Really Are, And Where I Really Am. Image by Nina Peterson.

The curation of the show encourages a puzzle-like viewing experience. Set on a plinth in the center of the main gallery, sheets of tracing paper implicitly invite visitors to match each drawn linear shape to its iteration in the paintings hung on surrounding walls. But this matching game is tricky. It raises questions rather than confirming suspicions.

Olive Moya, Clouds Are Not Decoration, By Any Means, 2025, acrylic on panel. Image by Nina Peterson.

Is the shape on the sheet of tracing paper labeled #25 reproduced in the upper right corner of both paintings titled Clouds are Not Decoration, By Any Means and Only Losers Don’t Feel Like Losers? Or does the eponymous non-ornamental cumulus take its form from another of Moya’s noodles on tracing paper?

Olive Moya, Only Losers Don’t Feel Like Losers, 2025, acrylic on panel. Image by Nina Peterson.

Despite the indeterminacy of such an attempt, the artist’s use of these particular designs in her paintings is apparent in the jagged cuts visible in some of the marks delineating the noodles on tracing paper. Slices open where the pen met paper over and over and over in the artist’s process of transferring the noodles to multiple substrates. These incisions suggest the violence of inscription but also a kind of liberatory action, in which self-identification might release a subject from the confines of an imposed identity.

Olive Moya, Fads For Whatever, 2025, acrylic on canvas. Image by Nina Peterson.

When power marks an individual in terms of predetermined identities, it creates a trap in which the subject struggles to escape the expectations and stereotypes for this identity category. Women, people of color, queer folx, and people with disabilities know this trap well. [6] But when claimed by a subject in collective solidarity and coalition-building, identity can empower, reorient, and serve as the grounds from which social and personal change can happen. [7]

Olive Moya, The Way The Sourness Overtakes The Cream, 2024, acrylic and graphite on mylar. Image by Nina Peterson.

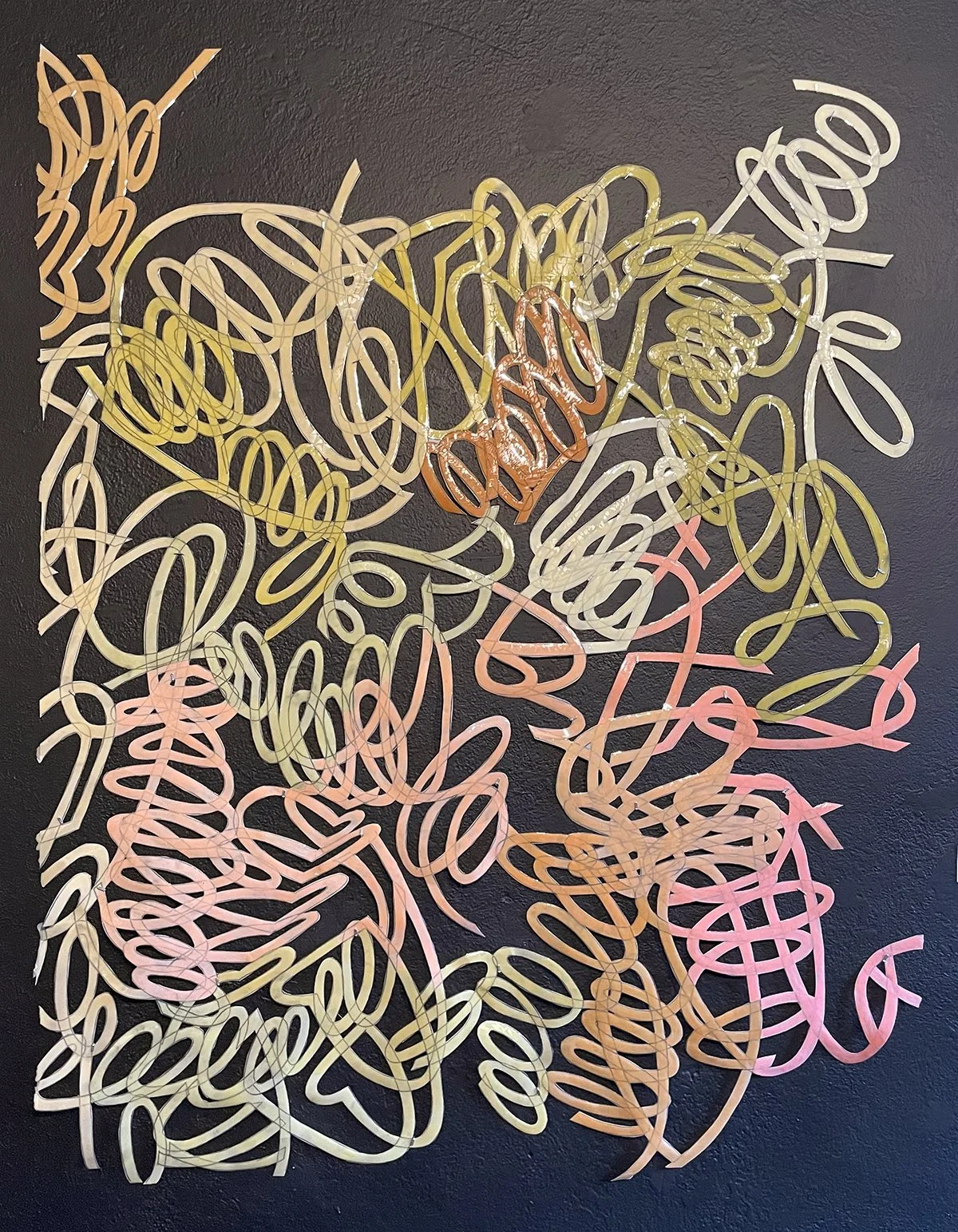

A process of change seems to be at play in The Way The Sourness Overtakes The Cream. Here, Moya’s noodles whip, swivel, and coil together in an animated knot of peachy pinks, putrid icterines, and chartreuse hues. Drawn on a sheet of mylar, further delineated by layers of acrylic paint, and cut from the polyester film, the translucent and shiny tangle curls dynamically away from the black wall of the project space.

Olive Moya, The Way The Sourness Overtakes The Cream (detail), 2024, acrylic and graphite on mylar. Image by Nina Peterson.

The title of the work derives from a line in Mary Oliver’s poem “We Should Be Well-Prepared,” a rumination on the inevitability of loss and the ephemerality of life. [8] Moya’s take on Oliver’s verse posits such change not as an object of lamentation but as a state of entanglement in which discrete elements connect and disengage, not fully coalescing into coherence but neither dissolving into utter chaos.

Olive Moya, More! More! #3, 2025, acrylic on panel. Image by Nina Peterson.

This process of change is how identity functions in Where You Really Are, And Where I Really Am. Always drawing upon and shaped by conventions, identity is also a site for constant reconfiguring and parody. This is the radical, subversive potential of identity: its ability to evade dominant structures through repetition with variability. [9] What is interesting about the iterativity of the noodles transferred via tracing paper to numerous surfaces is that the same noodle shape never looks identical across this body of work. Much like how letters and words take on and convey different meanings in relation to other words and letters, each noodle shape always looks different in play with other noodles, in other colors, and in different orientations.

Nina Peterson (she/her) is a Ph.D. candidate in art history at the University of Minnesota. Currently based in Denver, she researches histories of photography, film, and performance in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

[1] Olive Moya in “Olive Moya | Denver Visual Artist,” video interview produced by the Denver Art Museum, January 18, 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZoMDFJedyjI&t=45s.

[2] Lindsey Bell, exhibition guide for Olive Moya: Where You Really Are, And Where I Really Am, accessed August 29, 2025, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5fa8bca05b3b175c6ec3c53a/t/689e4c067235bd097e98b502/1755204614388/Where+You+Really+Are%2C+And+Where+I+Really+Am.pdf.

[3] Moya, “Olive Moya | Denver Visual Artist.”

[4] For a discussion of the relationship between language, identity, and social inscription, see Judith Butler, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (Routledge, 1990), 194-203.

[5] The exhibition guide asserts, “The fragility and intimacy of these new paintings on paper evoke the process of revealing every dimension of our identity — akin to peeking inside a private journal.” I’m more compelled by the guide’s description of the artist’s process as being a “visual game of telephone,” and I briefly extend that aesthetic analysis here.

[6] Here, I am thinking of representational visibility politics surrounding numerous identity categories. For a discussion of the problems of visibility politics and women, see Peggy Phelan, Unmarked: The Politics of Performance (Routledge, 1993). For a discussion of the trap of representation and Black artists, see Darby English, How to See a Work of Art in Total Darkness (The MIT Press, 2010). For a discussion of visibility politics and trans artists and activists, see Reina Gossett, Eric A. Stanley, and Johanna Burton, eds., Trap Door: Trans Cultural Production and the Politics of Visibility (The MIT Press, 2017). Moya’s use of abstraction (rather than representational naturalism) might be thought of as a tactic of navigating the possibilities and constraints of visibility politics attached to identity categories.

[7] Sara Ahmed, Queer Phenomenology : Orientations, Objects, Others (Duke University Press, 2006), 156.

[8] Mary Oliver, Red Bird: Poems (Beacon Press, 2008), 53.

[9] Butler argues that the enactment of gender, for instance, is performative: it comes about through the citation of gendered codes, which may then be played with and broken through parody. For Butler, the performative constitution of identity—how identity is a process of making rather than a pre-existing condition—in fact holds its potential for political change. Because discursive formations and regulations of identity depend on repetition of its codes, playing with these codes—enacting them with variation—holds subversive potential. Butler, Gender Trouble, 200-202.