CAMP: Queer Arts and Crafts & the Beauty of Imperfection

CAMP: Queer Arts and Crafts & the Beauty of Imperfection

Kin Studio and Gallery

4725 16th Street, Studio #104, Boulder, CO 80304

September 5, 2025–January 31, 2026

Admission: free

Review by Madeleine Boyson

At their first meeting in July 2025, Allyson McDuffie’s new studio assistants pronounced that they too would include work in her upcoming exhibition at Kin Studio and Gallery. McDuffie, the artist who owns the mixed-use space in North Boulder, chuckles when she tells me this. She’s still amazed and delighted by their temerity. “I’ve never met a group of people more confident in who they are,” praises the artist. [1] And she means it.

An installation view of CAMP: Queer Arts and Crafts & the Beauty of Imperfection at Kin Studio and Gallery. Image by Madeleine Boyson.

Six LGBTQ+ youths aided McDuffie in executing artworks and producing CAMP: Queer Arts and Crafts & the Beauty of Imperfection over two months and forty hours of workshop time. The artist anticipated her looming exhibition deadline and need for hands—twelve of them—to help realize a “comical and poignant” evocation of American summer camps “with a queer twist.”

Kin Studio and Gallery owner and artist Allyson McDuffie (third from left) with studio assistants (left to right) Graham Shepherd, Arcus Evans, Demi Howard, Celeste Wilson, and Copeland Shepherd at the exhibition opening in September 2025. Image by Dona and Niko Laurita, courtesy of Kin Studio and Gallery.

In waltzed Arcus Evans, Demi Howard, Savy Laubacher, Graham Shepherd, Copeland Shepherd, and Celeste Wilson. The thirteen- to sixteen-year-olds contributed to the (mostly) solo exhibition while learning about craft, curation, design, marketing, and pricing. What followed was a multigenerational exchange of ideas on art, community, queerness, and joy.

Allyson McDuffie, Proud Mama, 2025, cardboard, afghans, and hot glue, 34 x 26 x 2 inches. Image by Kin Studio and Gallery.

Allyson McDuffie, Hitch, 2025, cardboard, afghan, acrylic, faux fur feathers, and hot glue, 28 x 31 x 2 inches. Image by Liz Quan.

Anyone who knows McDuffie’s work will see her oeuvre stamped throughout CAMP. Proud Mama emerges from the artist’s frequently scrawled fowls. [2] Hitch, a crocheted pig carrying headless chickens, springs to life from a companion print across the room, echoing variations on McDuffie’s favored barnyard motifs and rural symbologies. Donkeys are also a mainstay in quintuplicate, crafted out of materials ranging from wedding vows to condoms.

An installation view of CAMP: Queer Arts and Crafts & the Beauty of Imperfection at Kin Studio and Gallery. Image by Madeleine Boyson.

CAMP began as an homage to McDuffie’s 1973 camp stay when she sought refuge in the arts building and made an eagle out of macaroni for her then-new stepfather. Father’s Day enlarges that bird with a pig’s head and experiments with new pasta shapes. Other sculptural works elicit comfort and use second-hand media such as the afghan quilts covering Old Salty and Proud Mama. Green nylon woven on aluminum folding chairs cradles a donkey in Aspen Ski Week, Ohio Style and similarly reminds McDuffie of her childhood in Ohio.

Allyson McDuffie, Do these rubbers make by butt look big?, 2025, cardboard, leather, strap-on harness, riding crop, charms, and condoms, 34 x 38 x 11 inches. Image by Kin Studio and Gallery.

But the work in CAMP is not centered solely on nostalgia. Just as macaroni birds and campsite chairs get revamped, so too do McDuffie’s memories. Do these rubbers make my butt look big? is “for the leather boys,” in a nod to the queer submissive subculture. A riding crop tail, colorful Trojan® condoms, and a strap-on harness collide with dainty Valentine’s Day charms—”I’m Yours” sits on the rump. But for the artist, these elements call to mind her former partner who couldn’t escape internalized homophobia, especially regarding leathermen at pride parades. The sculpture uses comedy to acknowledge the work queer people do to explore our personal identities even as we come to grips with a culture steeped in puritanical heterosexuality that ostracizes expressions “deviating” from those norms.

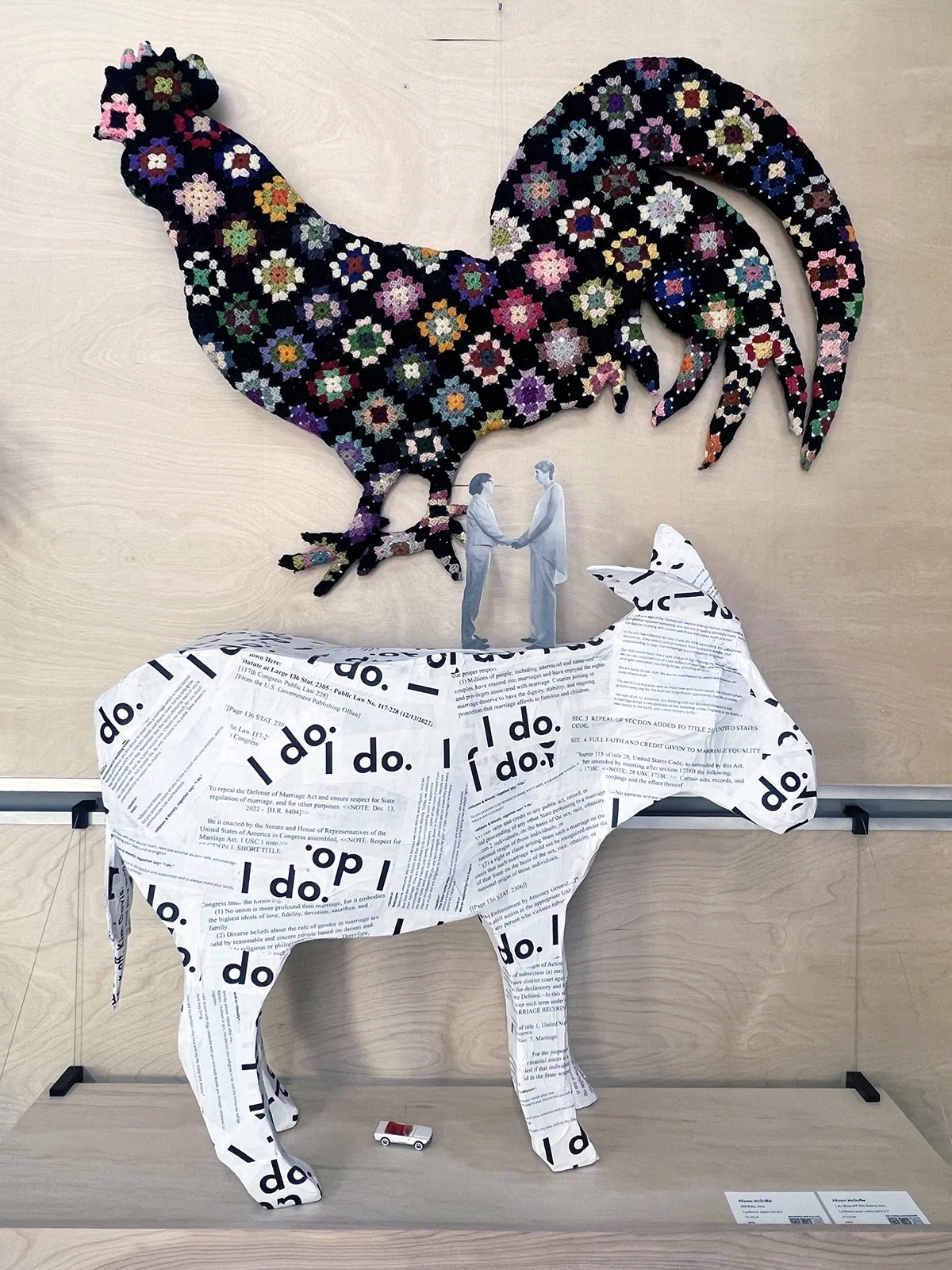

Top: Allyson McDuffie, Old Salty, 2025, cardboard, afghan, and hot glue, 34 x 42 x 2 inches. Bottom: Allyson McDuffie, I do. (Fuck off, Kim Davis.), 2025, cardboard, papier mâché, and paper text, 33 x 36 x 10 inches. Image by Madeleine Boyson.

Elsewhere, McDuffie presents I do. (Fuck off, Kim Davis.), a papier-mâché donkey covered in the artist’s wedding vows and text from the Respect for Marriage Act, a federal statute passed by the 117th United States Congress to recognize same-sex and interracial marriages. [3] McDuffie and her partner Wendy Gram stand atop the donkey in direct protest to the titular Kim Davis, a former Kentucky clerk who refused to issue marriage licenses so as to avoid issuing them to same-sex couples.

Allyson McDuffie, Some Pig, 2025, cardboard and yarn, 32 x 37 x 10 inches. Image by Kin Studio and Gallery.

Some Pig nearby is more subtle with its layered connotations but is no less substantial. Here a cardboard donkey is wrapped in yarn in a nod to binding, which is the use of compression garments or tapes to flatten the chest in gender affirming care. The original work had to be rewound, says McDuffie, because it ended up too thick and shapeless.

Using the sculpture as a teaching moment and an opportunity to regroup (much to her assistants’ dismay at the lost effort), the work took on another significance as an homage to textile artist Judith Scott; a literary reference to compassion, friendship, and life’s frailties in Charlotte’s Web by E.B. White; and a commentary on the chaotic, sometimes monotonous process of personal becoming.

Allyson McDuffie, Merit Badges (top left to bottom right): Dyke, Butch, Tomboy, Gay, Friendship, and Queer, 2025, tufted yarn, each 22 x 22 x 1 inches. Image by Liz Quan.

The works ripest for further harvest, however, are McDuffie’s Merit Badges. These tufted rugs inspired by scout sashes reclaim formerly derogatory terms used against the queer community. “Dyke,” “butch,” “queer,” “tomboy,” and “gay” all proclaim proficiency in performing gender, sometimes earned at a great cost, and pride in these self-identifying labels. Where rugs would otherwise be underfoot, the badges hang as though on a Gold Award-winning sash and both parody and promote the constant work involved in learning oneself. Their bold colors also embody the multilayered meaning of the word “camp” as both the ubiquitous summer program and the “extravagantly flamboyant or affected” term often associated with queer culture. [4]

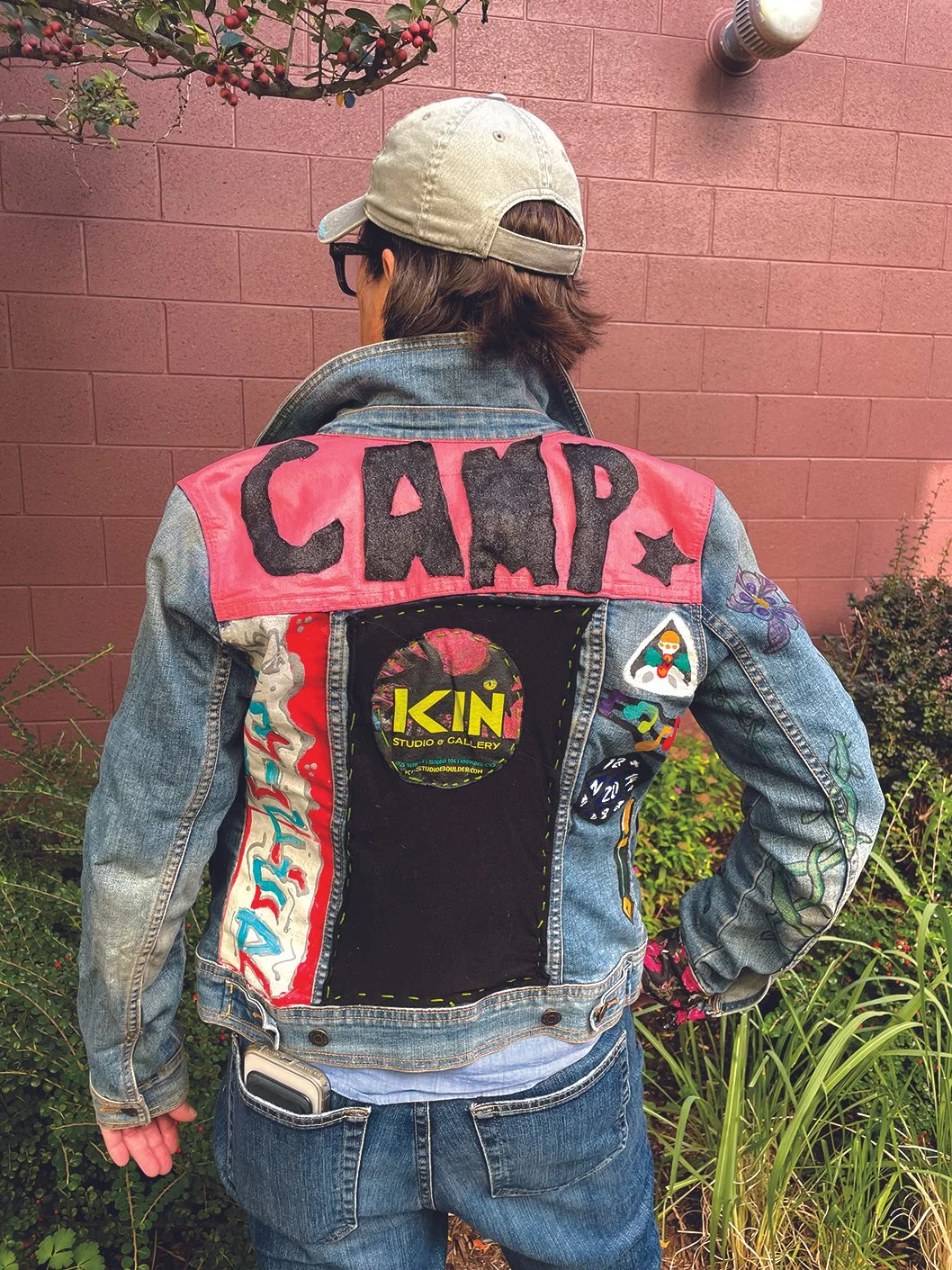

Arcus Evans, Demi Howard, Savy Laubacher, Graham Shepherd, Copeland Shepherd, and Celeste Wilson, Battle Jacket, 2025, mixed media. Image by Liz Quan.

McDuffie’s studio assistants’ works stand in a designated corner, honored by McDuffie in her introductory text and also her effusive spoken praise. Battle Jacket is a group-made garment referencing visible identifiers used to signal to other people in countercultural scenes. It also encompasses the past, present, and future of queerness in wearable camp. [5] Nearby, thoughtful artist statements reveal probing questions about being non-binary (Copeland) and trans (Demi), others’ emotional and personal depths (Graham), queer joy (Celeste), and visual impairments or imperfections (Arcus).

Allyson McDuffie, Chicken Run, 2025, cardboard, pasta, glue, spray paint, and faux feathers, 22 x 36 x 5 inches. Image by Kin Studio and Gallery.

CAMP’s “imperfections” generally reference strengths, however, calling to mind manifold motifs woven throughout McDuffie and her assistants’ works. Traditionally overlooked media, repair and reclaimed materials, process over product, and upsetting the quotients of mainstream taste in favor of building community (which is ultimately more lasting), are all part of McDuffie’s practice. And that’s what sets up CAMP: Queer Arts and Crafts & the Beauty of Imperfection as a “politically conscious” exhibition—the work is less about statements made (however strongly), and more about the growth that comes with openness.

Studio assistants Celeste Wilson (left) and Graham Shepherd (right) working on Allyson McDuffie’s Some Pig, 2025, cardboard and yarn, 32 x 37 x 10 inches. Image by Kin Studio and Gallery.

McDuffie has lived and worked in Boulder since 1992 and plays with her work so consistently that it’s obvious where CAMP originates. But the exhibition’s success lies in the artist’s creative capacity for merging past and present. By celebrating self-knowledge in the same breath as becoming, and for seeing queerness not as a static otherness, McDuffie uses art as a portal to life itself. [5]

Madeleine Boyson (she/her) is an Editorial Coordinator at DARIA and a Denver-based writer, poet, and artist. She holds a BA in art history and history from the University of Denver.

[1] All quotes come directly from the artist or the exhibition introductory text, written by Allyson McDuffie.

[2] All works in CAMP: Queer Arts and Crafts & the Beauty of Imperfection were created in 2025 and are by Allyson McDuffie, unless otherwise noted.

[3] Pub. L. 117-228, also known as the Respect for Marriage Act, was signed into law by President Joe Biden. The statute repeals the Defense of Marriage Act and renders same-sex and interracial marriage as federal law.

[4] The sixth Merit Badge on the wall references the “Friendship” pin from the American Girl Scouts. On a separate wall is Wendy Gram’s first and only artwork in an exhibition, Hobo Bag, which shows a red and white polka-dotted bag on a stick.

[5] Queer People, a school desk burned with imagery, echoes the exhibition throughline with a quote by Alexander Leon: “Queer people don’t grow up as ourselves, we grow up playing a version of ourselves that sacrifices authenticity to minimize humiliation and prejudice. The massive task of our adult lives is to unpack which parts of ourselves are truly us and which parts we’ve created to protect us.”