Deal, or, How I Became Radioactive

Emily Joyce: Deal, or, How I Became Radioactive

David B. Smith Gallery

1543 A Wazee Street, Denver, CO 80202

January 17–February 21, 2026

Admission: free

Review by Madeleine Boyson

A green man once told a donkey that ogres were like onions, but he may as well have been talking about Emily Joyce’s work. [1] The paintings in her third solo exhibition at David B. Smith Gallery are practically peelable, layered as they are with color, shape, symbolism, history and science, mock texture, mathematics, and source material. But unlike onions (which may cause tears), the art in Deal, or, How I Became Radioactive, now on view through February 21, has a friendly exhilaration that chatters off the walls. And best of all, Joyce’s work attests that the best art always knows the shape of its own container.

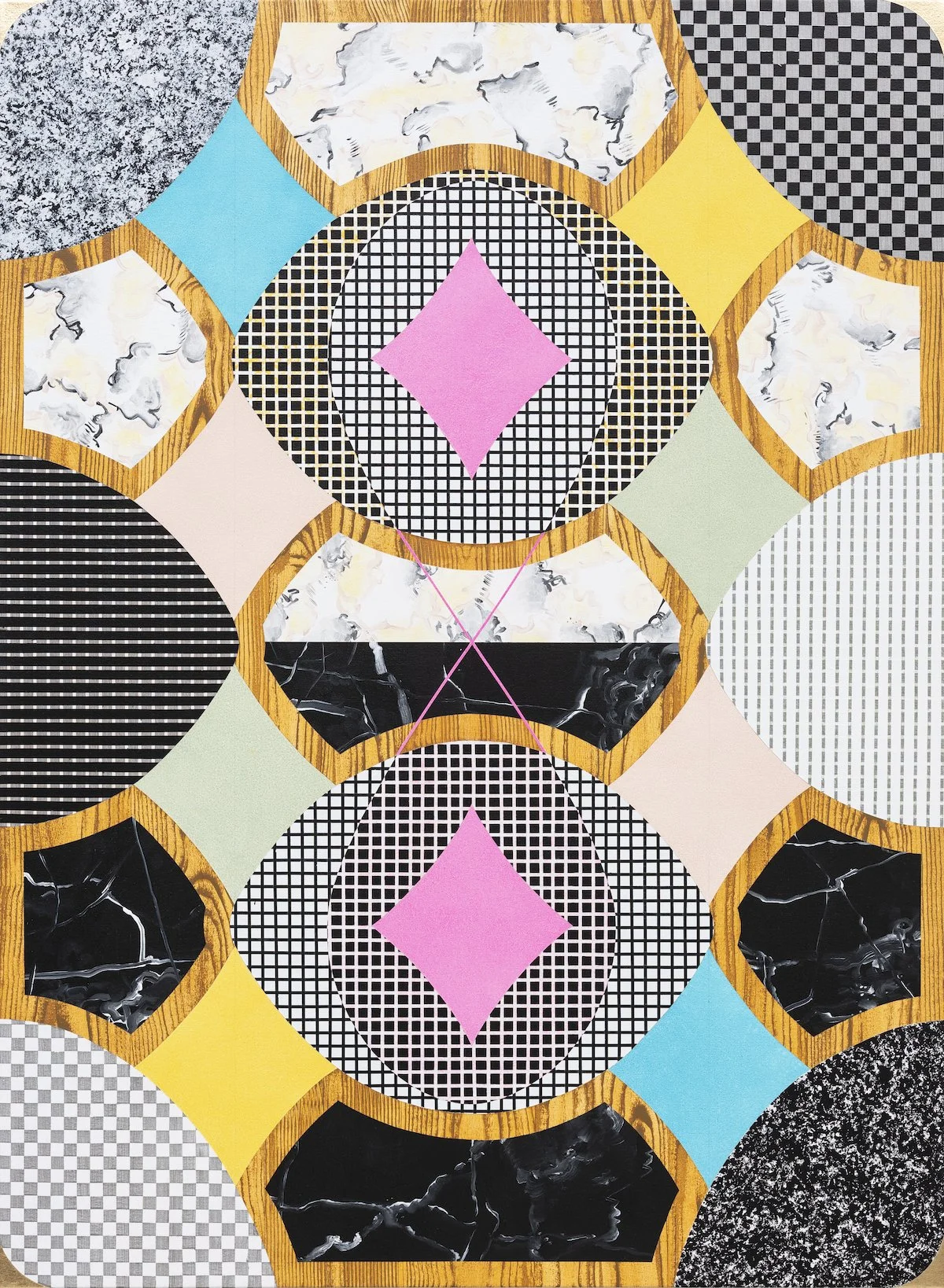

Emily Joyce, Lot 239: Ten of Diamonds, 2025, acrylic paint and metal leaf on canvas, 49 x 36 inches. Image by Wes Magyar, courtesy of Emily Joyce and David B. Smith Gallery.

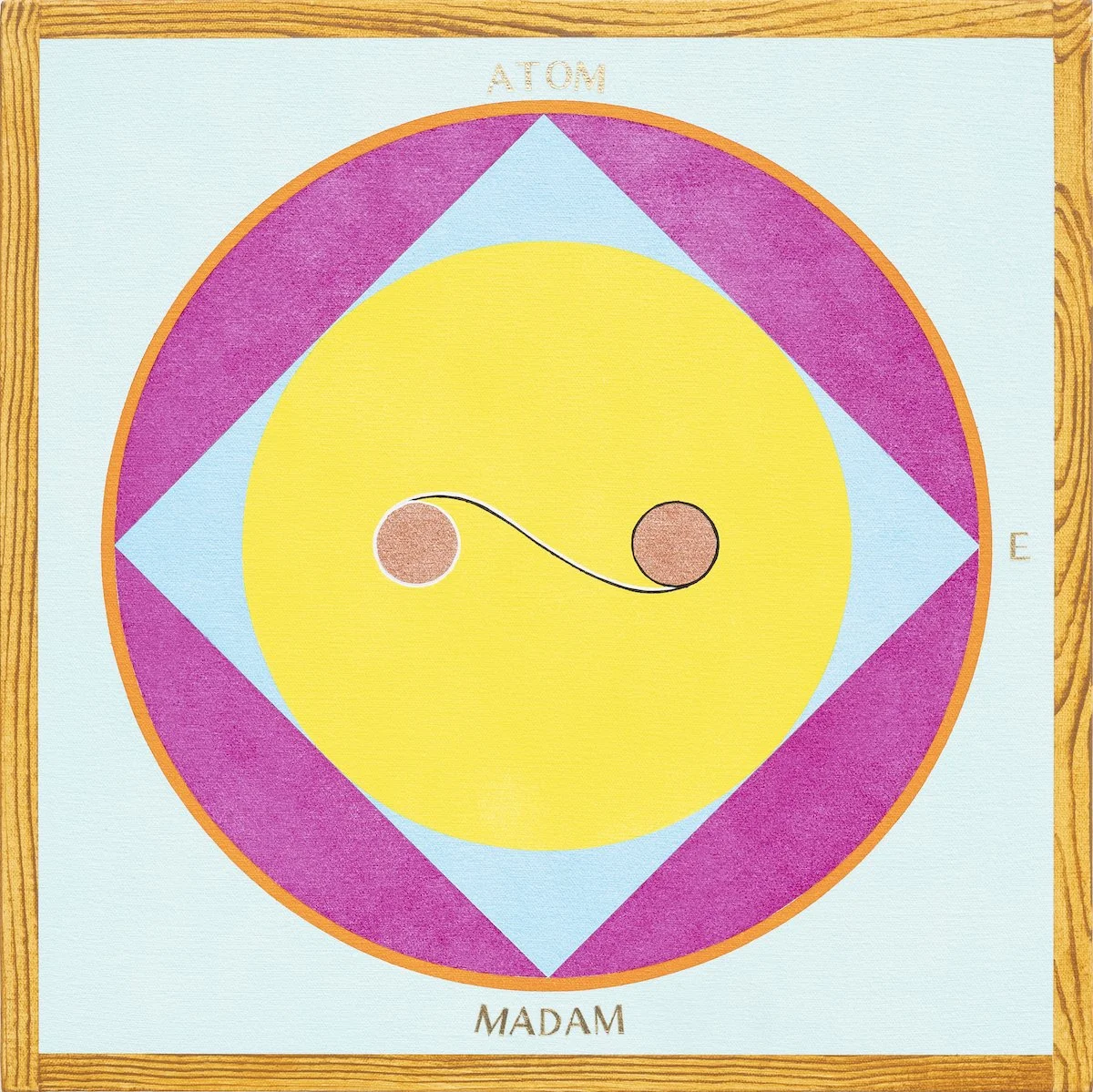

The artist’s fixation on self-imposed constraints is evident in the geometry that animates Deal. The gallery is full of interlocking shapes with crisp lines. Pentagons click together with diamonds in Lot 239: Ten of Diamonds (2025), while a square holds a circle holding a square holding a circle in Marie Curie’s Radioactive Cookbook (2025). Rigorously measured arches and ovals similarly echo themselves to-scale in Upside Down in the Mirror 3 (2024) and Heaven’s Gate Nebula (2023).

Emily Joyce, Marie Curie’s Radioactive Cookbook, 2025, acrylic paint and metal leaf on canvas over panel, 16 x 16 inches. Image by Wes Magyar, courtesy of Emily Joyce and David B. Smith Gallery.

Much of this Euclidean bliss comes from playing cards, which Joyce uses as a framework for her compositional forms and the exhibition’s conceptual premise. Borrowing from Alan Watts’s consideration that life is not “a serious problem to be solved but a playful dance or game to be experienced,” the works in Deal do indeed frolic.

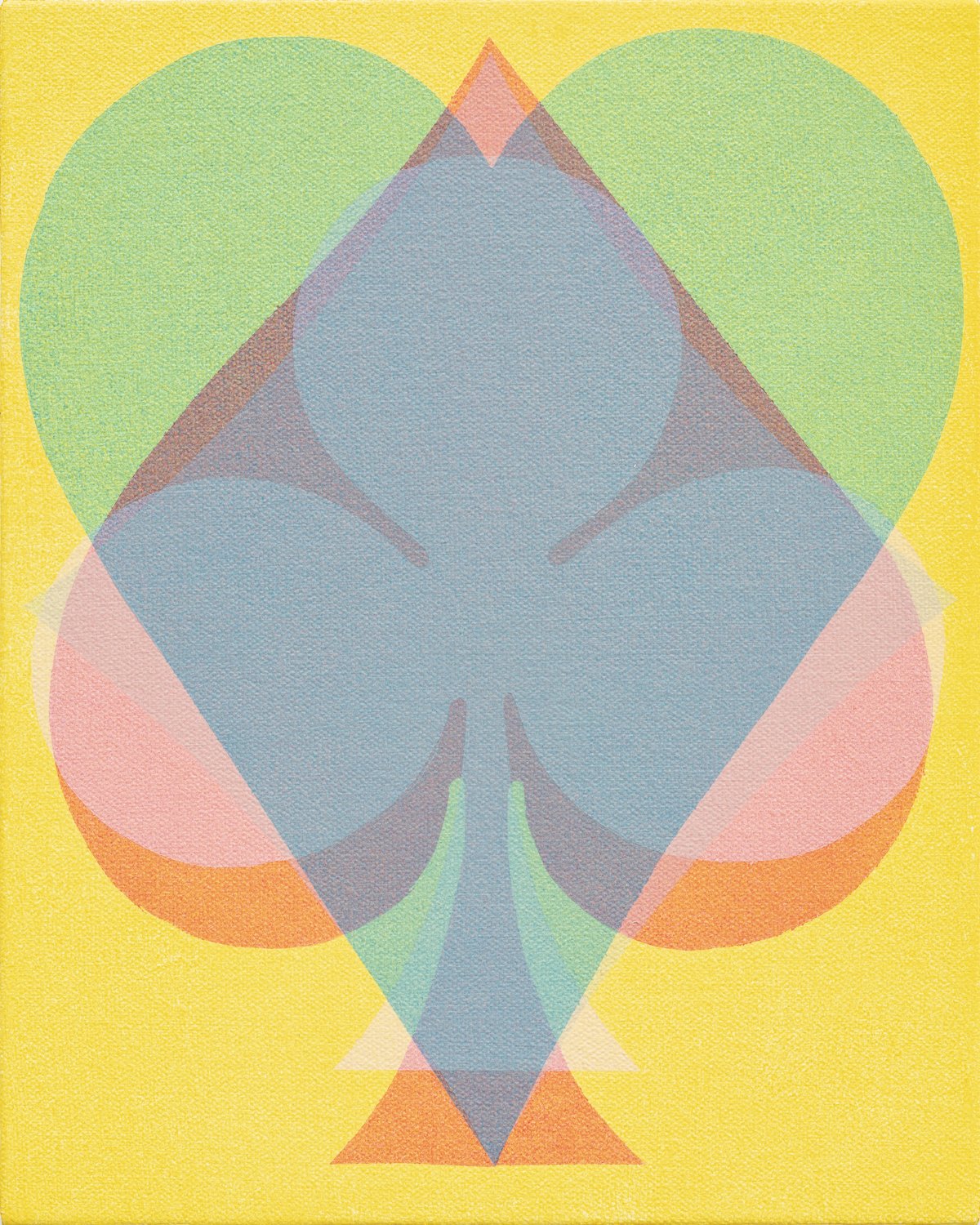

Emily Joyce, Riffle Shuffle Spade, 2025, acrylic paint on canvas, 10 x 8 inches. Image by Wes Magyar, courtesy of Emily Joyce and David B. Smith Gallery.

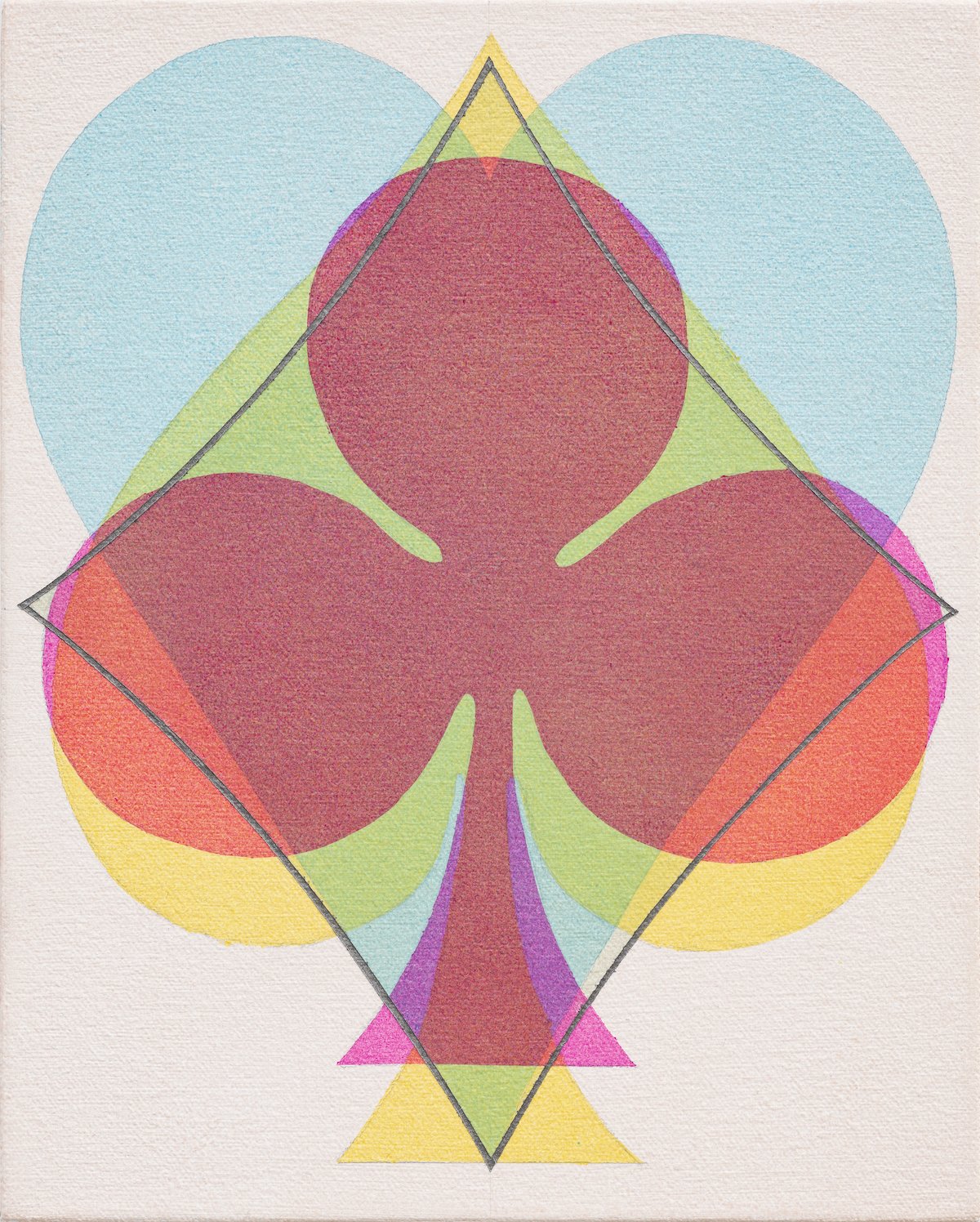

Emily Joyce, Cutting Diamond, 2025, acrylic paint on canvas, 10 x 8 inches. Image by Wes Magyar, courtesy of Emily Joyce and David B. Smith Gallery.

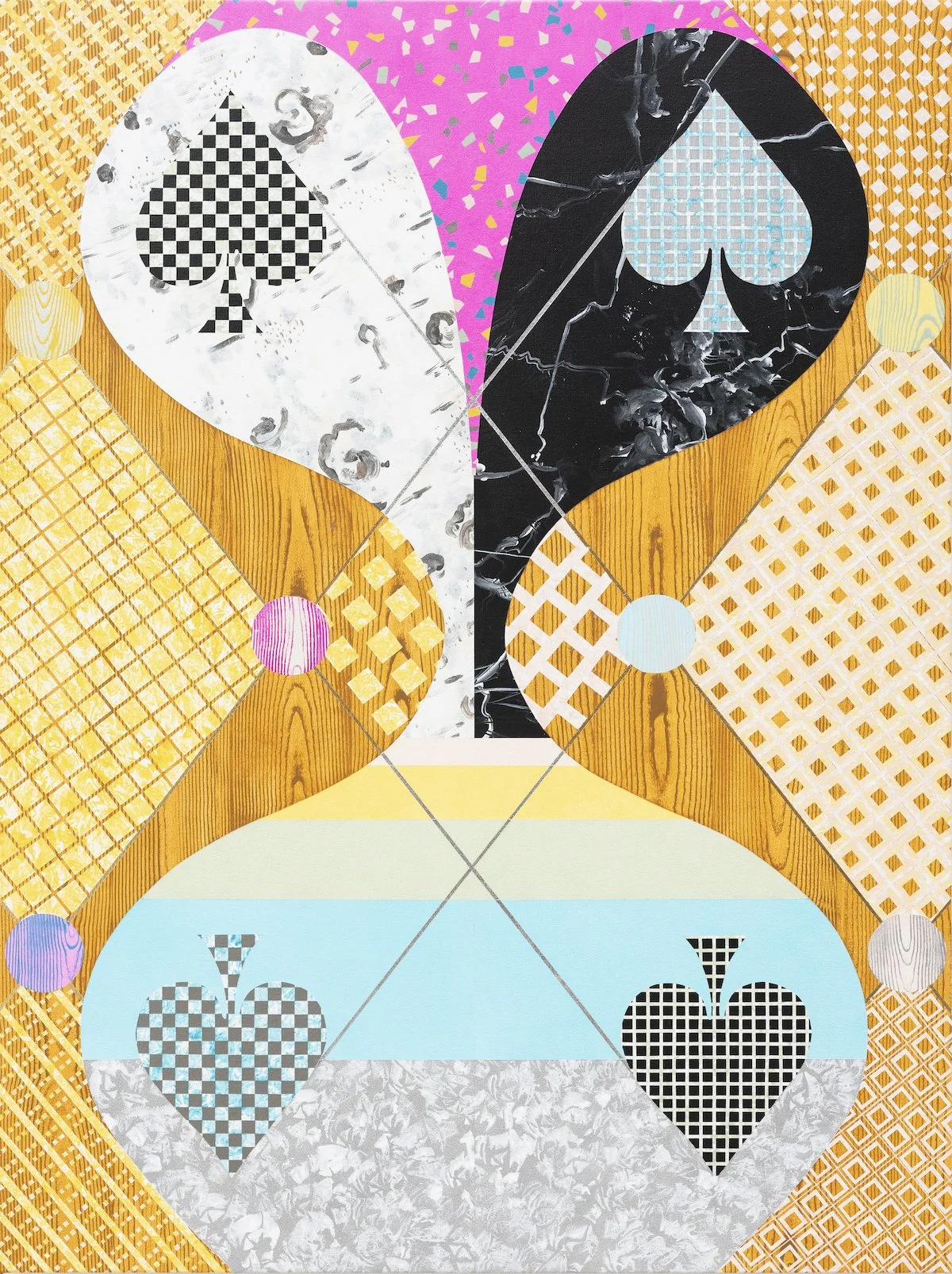

Spades, clubs, diamonds, and hearts bubble and pop from the walls in thin washes. Often overlaid like the colored cellophane found in a mid-century art class, the artist’s small Riffle Shuffle and Cutting paintings demonstrate basic color theory in a fun new way. [2]

Emily Joyce, Heaven’s Gate Nebula, 2023, Flashe vinyl paint and acrylic on canvas over panel, 16 x 20 inches. Image by Wes Magyar, courtesy of Emily Joyce and David B. Smith Gallery.

Part of Deal’s success lies in Joyce’s palette. Her latest work is based on colors seen at Yosemite National Park and the artist utilizes them with few exceptions. Blue, green, yellow, and neutrals all track, even if they pulse in neon, as do the artist’s hand-drawn, nature-inspired, marbleized, and wood grain patterns. But the pink? Inspired by a tourist’s cowboy boots fresh off a bus. Talk about layers.

Emily Joyce, All In (Three Hands), 2025, acrylic paint and metal leaf on canvas, 58 x 67 inches. Image by Wes Magyar, courtesy of Emily Joyce and David B. Smith Gallery.

In All In (Three Hands) (2025), Joyce takes her constraints to the cliff’s edge by drawing cards to determine the painting’s design. Though leaving a composition up to chance might seem like a step away from limitations, the artist’s gamble takes on a divinatory mist. While Joyce did not create her composition whole cloth, she chose the deck and didn’t waver in following the cards’ instructions, letting probability mark the outer boundaries of the work.

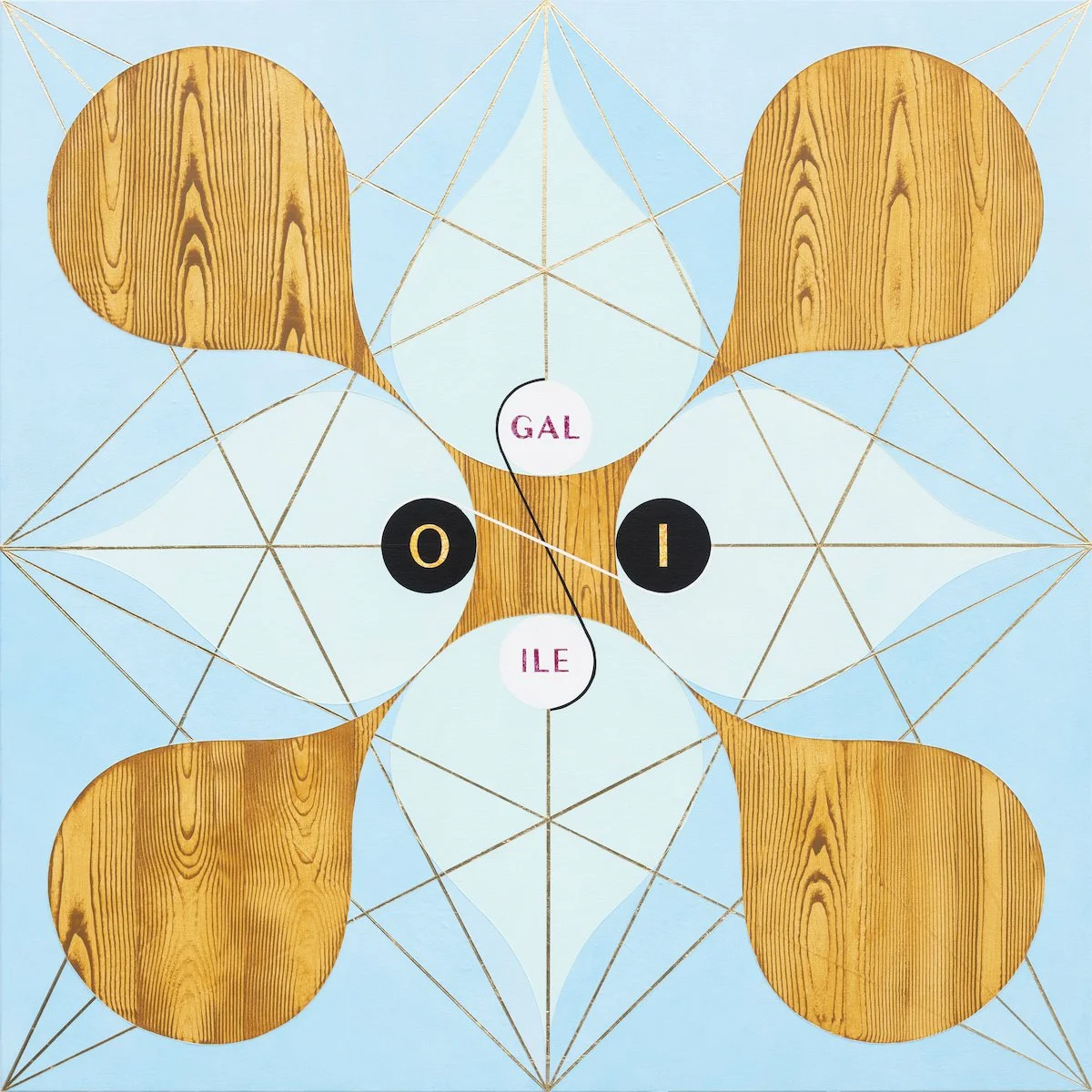

Emily Joyce, Galileo’s Fidget Spinner, 2025, acrylic paint and metal leaf on canvas over panel, 40 x 40 inches. Image by Wes Magyar, courtesy of Emily Joyce and David B. Smith Gallery.

With intentional colors and shapes forming a rationale for Deal, Joyce is free to tinker with inspirations, references, and philosophies. Take, for instance Galileo’s Fidget Spinner (2025), which layers mid-century teardrops over a flattened, eight-pointed star that could have easily come out of the title scientist’s own journals. Joyce connects Galileo Galilei’s (1564-1642) nom and prenom by their root (the first six letters shared by each) and posits the suffixes “I” and “O” as opposing forces. The exhibition’s accompanying Field Guide then satirizes a recently popularized fidget toy, adding another stratum so that the work lands like a meme—you’ll only get the joke if you know all of the references. Either that or you’re chronically online.

Emily Joyce, Discarded Descartes on the Bedroom Wall, 2026, acrylic paint on canvas over panel, 30 x 30 inches. Image by Wes Magyar, courtesy of Emily Joyce and David B. Smith Gallery.

Art historical references also punctuate Joyce’s playtime, and she calls on artisans from as far back as the 13th century. Georges de la Tour’s duplicate paintings Cheat with the Ace of Clubs (1634) and The Card Sharp with the Ace of Diamonds (1638) filter through the Riffle and Cutting series, while Joseph Cornell’s three-dimensional Discarded Descartes (1954-56) in the Menil Collection gets such flattened treatment in Joyce’s Discarded Descartes on the Bedroom Wall (2026) that Clement Greenberg is dancing in his grave.

Emily Joyce, Mezquita Gate with Love, 2023, acrylic on canvas, 48 x 38.5 inches. Image by Wes Magyar, courtesy of Emily Joyce and David B. Smith Gallery.

Joyce further references Robert Indiana referencing Charles Demuth referencing William Carlos William in All In (Three Hands) with her golden number five, and even the ablaq, the alternating and multicolored stonework, of the Mosque-Cathedral of Córdoba makes an appearance in Mezquita Gate with Love (2023).

Emily Joyce, Falling Slinky, 2025, acrylic paint and metal leaf on canvas over panel, 18 x 18 inches. Image by Wes Magyar, courtesy of Emily Joyce and David B. Smith Gallery.

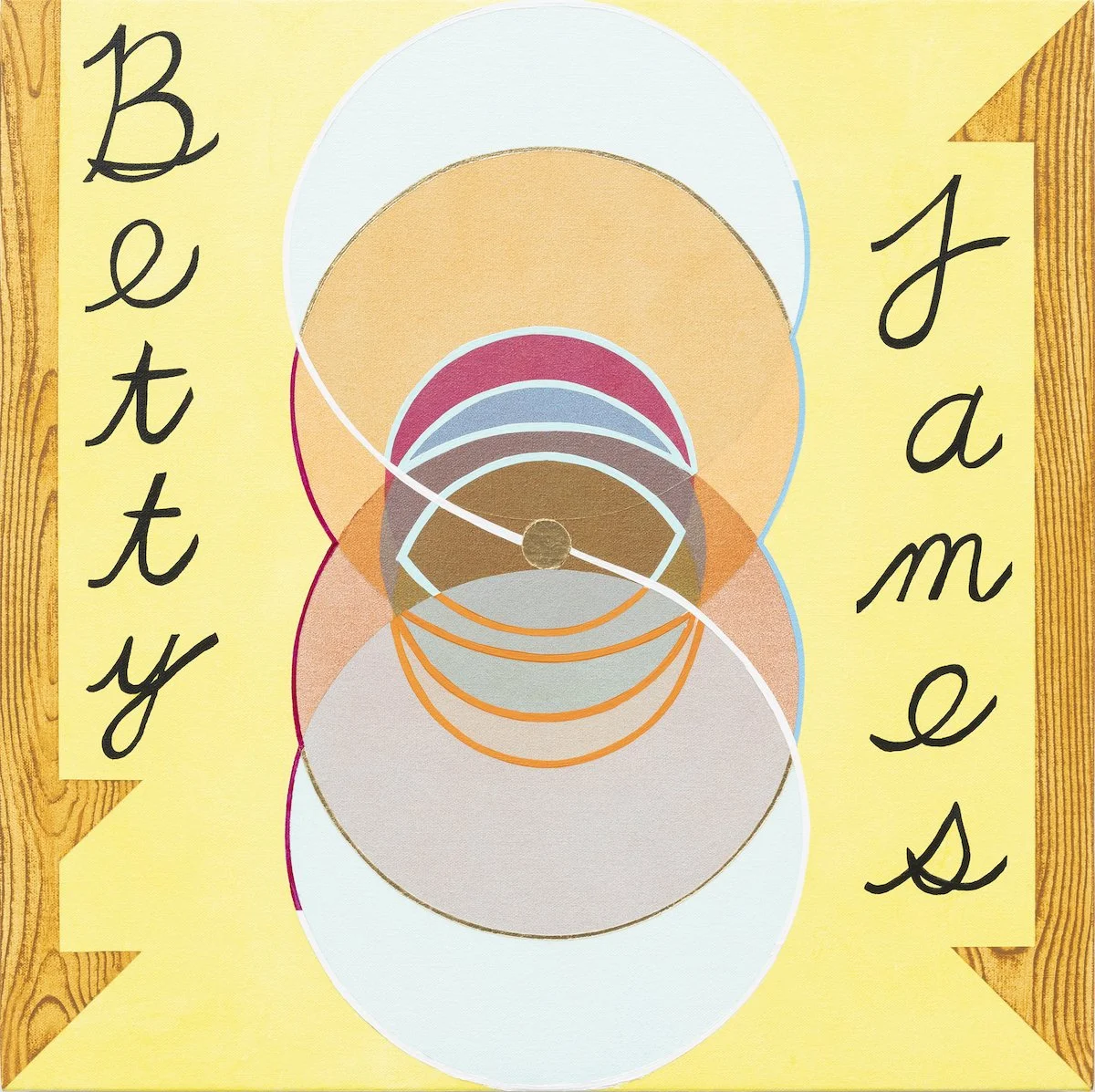

History similarly makes an appearance in Deal, as the artist plucks Madame Marie Curie from her radioactive lab and Betty James through the portal of Slinky® fame. In Falling Slinky (2025), Joyce extrapolates the physics of the popular kid’s toy from its three-dimensional form and demonstrates its mechanism in what reads like an excision circle flanked by two monkey wrenches. The latter actually represents the transfer of energy as a Slinky “walks” down a set of stairs. It’s this attention to detail that makes Joyce’s work sing—with so many layers to pare down, is there even a center to the onion?

An installation view of Emily Joyce’s Deal, or, How I Became Radioactive exhibition at David B. Smith Gallery. Image by Wes Magyar, courtesy of Emily Joyce and David B. Smith Gallery.

Deal, or, How I Became Radioactive does not require a pre-existing education in art or history to enjoy, and many viewers will find Joyce’s paintings activating without much context. But the paintings get chatty as soon as the viewer starts peeling, uncovering each new subtle subtext and riddle and wink. It is work that does not demand knowledge, but is still enhanced by knowing.

An installation view of Susan Wick’s solo exhibition More by Wick at David B. Smith Gallery’s Project Room. Left: Huh, What Did You Say?, 2026, acrylic on canvas, 18 x 18 inches. Center: Ode to a Life, 2026, acrylic on canvas, 40 x 40 inches. Right: Pink, 2026, acrylic on canvas, 24 x 18 inches. Image by Madeleine Boyson.

With such evolved work in David B. Smith’s Main Gallery, it’s a relief to find a similarly evolved artist in the Project Room, where a lesser painter would be overshadowed by Joyce’s levity. Yet lifelong artist Susan Wick more than holds her own in More by Wick, also her third solo exhibition in the gallery. The artist produced a new body of work for the show (declining any edits to the checklist) that propels the viewer into new vistas and still lifes that spill from the Project Room out into the hall.

Emily Joyce, Moths Eat Paper: Four of Spades, 2026, acrylic paint and metal leaf on canvas, 48 x 36 inches. Image by Wes Magyar, courtesy of Emily Joyce and David B. Smith Gallery.

Taken together, Deal, or, How I Became Radioactive and More by Wick offer complementary tones rooted in mischief and strict personal parameters. Both artists understand the shape of their work conceptually and are therefore better able to transcend those constraints when the art calls for it. With a visual language of play at the fore, David B. Smith gallery brings a simultaneously impish and serious duo to Denver’s art scene. That feels crucial right now. Especially now.

Madeleine Boyson (she/her) is an Editorial Coordinator at DARIA and a Denver-based writer, poet, and artist. She holds a BA in art history and history from the University of Denver.

[1] See Shrek (DreamWorks Pictures, 2001): youtube.com/shorts/LEmFWRWLeGU?si=QVMtxIzE5Yze6-71.

[2] From the exhibition press release.