What We Hold On To

What We Hold On To

Black Cube Headquarters

2925 S. Umatilla Street, Englewood, CO 80110

September 5–December 12, 2025

Admission: free

Review by Dani/elle Cunningham

Black Cube Nomadic Art Museum rarely presents exhibitions at its headquarters—a warehouse repurposed into a haunting cavern, painted entirely black on the inside. You enter the structure through an old loading dock, nodding to its original purpose and lending resonance to this exhibition, which reflects on memory, preservation, and the passage of time. Mirroring the dark recesses of Black Cube’s institutional memory, the exhibition text describes the building as “a spatial form born to hold things, if only temporarily.” [1] In this sense, the exhibition’s title, What We Hold On To, refers not only to what we possess, but also to what we have been denied, the forces preventing us from holding on, and the ways letting go can offer a form of release.

An installation view of the exhibition What We Hold On To featuring works by Martin Creed, SANGREE, Amber Cobb, Marek Wolfryd, and Cristóbal Gracia at Black Cube Headquarters (BCHQ) in Englewood, Colorado. Image by Third Dune Productions, courtesy of Black Cube Nomadic Art Museum.

Though the space is enormous, the exhibition is confined to roughly 800 square feet near the entrance for a more intimate experience. Martin Creed’s monumental toilet paper pyramid, Work No. 1782, is the first and most immediately visible artwork in the space, evoking the resource hoarding of the COVID-19 pandemic. The irony is sharp: while pyramids once entombed pharaohs and rulers of ancient civilizations, here the form serves as a tomb for consumerism itself. It may even be read as a future monument, commemorating resources we have lost.

An installation view of What We Hold On To at Black Cube Headquarters. Image by Third Dune Productions, courtesy of Black Cube Nomadic Art Museum.

Throughout the exhibition, hundreds of silver mylar letter balloons scatter across the floor, spilling from corners and slipping out from beneath shelves to form Marek Wolfryd’s Content Creation in the Age of Globalized Reproduction. The work alludes to the glut of social media content while recalling Walter Benjamin’s seminal essay The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction—a cornerstone of art theory curricula. The balloons collectively spell out a passage from Benjamin’s text, reflecting on how the mass reproduction of art erodes the authenticity that is tied to a singular time and place, even as it expands public access. [2]

A detail view of Marek Wolfryd’s Content Creation in the Age of Globalized Reproduction, mylar balloons. Image by Paloma Jimenez.

The biting irony of Wolfryd’s installation lies in its reliance on layers of conceptual framing—a style of art often inaccessible to the average viewer—while grounding itself in a theoretical text that many will never have read. This tension mirrors the very ideas it stages: how meaning is reproduced, distributed, and inevitably distanced from its original context. Like the mylar balloons that are mass produced and destined to deflate in a garbage heap somewhere, memory becomes hazy over time, its clarity fading even as its influence lingers.

An installation view of What We Hold On To showing works by Martin Creed, SANGREE, Viviane Le Courtois, Marsha Mack, Anuar Maauad, Marek Wolfryd, and Cristóbal Gracia at Black Cube Headquarters. Image by Third Dune Productions, courtesy of Black Cube Nomadic Art Museum.

Moving deeper into the exhibition, most of the artworks are arranged among towering shelves, which the exhibition text notes are custom-fabricated pallet racks. [3] They call to mind not only the building’s past life, but also scientific specimens or art storage systems, as well as other industrial means of preserving objects. This, too, underscores themes of stewardship and remembrance, with the shelving both physically and metaphorically elevating objects while safeguarding their histories in an era marked by historical erasure and the flood of artificial intelligence slop.

Several artworks are positioned on top shelves and shielded by fabric panels, evoking a sense of fragility—as if they are too delicate or elusive to be fully seen. Drawn from Black Cube’s collection and previously exhibited, these artworks reemerge like ghosts, their forms as difficult to grasp as memories dimmed by time. They are intentionally placed out of reach, signaling their significance while reminding viewers that some things in life remain beyond our grasp.

An installation view of SANGREE’s Florence and Krzywy Las, fiberglass, resin, and clay. Image by Paloma Jimenez.

Among these lofty objects are Florence and Krzywy Las—fiberglass, resin, and clay vessels by the artist duo Rene Godinez-Pozas and Carlos Lara, known as SANGREE. First shown in Black Cube’s 2019 exhibition The Fulfillment Center, these works merge ancient Mesoamerican traditions with modern manufacturing, evoking layers of cultural memory. They are displayed alongside their shipping crates, underscoring how the structures that protect them also hold visual significance.

Significantly, these vessels belong to SANGREE’s Calli series, whose title translates loosely from Nahuatl as “house” or “building.” Though created years before this exhibition, the title resonates uncannily here, as the works sit beside the very housings—crates and containers—that safeguard objects within museum collections.

An installation view of Anuar Maauad’s selections from WE ARE BODIES (The Archaeology Files), 2022, acrylonitrile butadiene styrene, polyester resin, and enamel paint. Image by Third Dune Productions, courtesy of the artist and Black Cube Nomadic Art Museum.

Anuar Maauad’s WE ARE BODIES (The Archaeology Files) #10 and #5 sit on the top shelves too, offering a glimpse into the artist’s 2022 project in which he led workshops with Denverites to create sculptural self-portraits. These sculptures were then transformed into large-scale, 3-D-printed sculptures. By elevating everyday likenesses into monumental forms, the works honor both individual and collective memory, turning fleeting expressions of selfhood into enduring artifacts.

An installation view of Amber Cobb’s Negotiating the Rations, 2025, chains, fragments of personal and found objects, and biological matter, commissioned for the What We Hold On To exhibition. Image by Paloma Jimenez.

In the interior space of the towering shelves, several artworks are suspended respectively by chains, rings, and rope, each one signifying connections to memory through diverse materials. These varied methods of suspension suggest that memory itself is held in place by fragile, shifting supports—always tethered, yet never entirely secure.

Marsha Mack, Tethered, 2025, glazed ceramic, cotton rope, and cast glass, each pendant: 7.5 x 6.5 x 1.75 inches, 70 inches long (installation dimensions variable). Image by Paloma Jimenez.

In Tethered, Marsha Mack presents two objects bound together and suspended by rope, each bearing an image of a young woman—two sides of the self held in tension. The work gestures to a balancing act between the artist’s Vietnamese and American identities, while also reflecting the duality within her practice: hybrid artworks that merge glazed ceramics with added materials. Evoking memory, the pieces capture small, personal moments from the artist’s daily life, presenting fragments of identity held together across time, culture, and form.

Marsha Mack, Double Berry, 2025, glazed ceramic, 16.5 x 15 x 6 inches. Image by Paloma Jimenez.

Mack’s four other playful ceramic sculptures offer a welcome respite from the exhibition’s heavier works. Each one is tactile, with their bright colors and adornments—body jewelry, rope, a box of strawberry Pocky®, and even rice—inviting a sense of relatability amidst the more conceptual works.

An installation view of Jerónimo Reyes-Retan’s Nosotros tenemos los relojes, pero ustedes tienen el tiempo / We have the watches, but you have the time (No. 02), 2025, two-channel sound reproducing metal device and an LED sign., reenvisioned for the What We Hold On To exhibition at Black Cube Headquarters. Image by Third Dune Productions, courtesy of Black Cube Nomadic Art Museum.

Similarly, Jerónimo Reyes-Retana’s installation combines a sound-producing metal bar suspended by chains with an LED sign, using time as a metaphor for the relationship between bodies of power and ordinary people. The artist spells out this idea visually on the LED sign while punctuating the space with a grating eruption of sound every twelve minutes. [4] The sound amplifies the scrolling text on the LED screen: Nosotros tenemos los relojes, pero ustedes tienen el tiempo (We have the watches, but you have the time), which also serves as the work’s title.

A detail view of Jerónimo Reyes-Retan’s Nosotros tenemos los relojes, pero ustedes tienen el tiempo / We have the watches, but you have the time (No. 02),2025, two-channel sound reproducing metal device and an LED sign, reenvisioned forthe What We Hold On To exhibition. Image by Paloma Jimenez.

Whereas Mack’s work grapples with an internal tension of selfhood, Reyes-Retana’s piece reflects a dualistic tension between “we” and “you.” The phrase, drawn from language used by the Taliban in reference to the U.S. invasion of the Middle East, underscores a paradox of power—those with control over mechanisms versus those who hold the deeper resource of time.

An installation view of Kija Lucas’s The Museum of Sentimental Taxonomy Vitrine #12, 2014–2025, archival pigment print. Image by Third Dune Productions, courtesy of the artist and Black Cube Nomadic Art Museum.

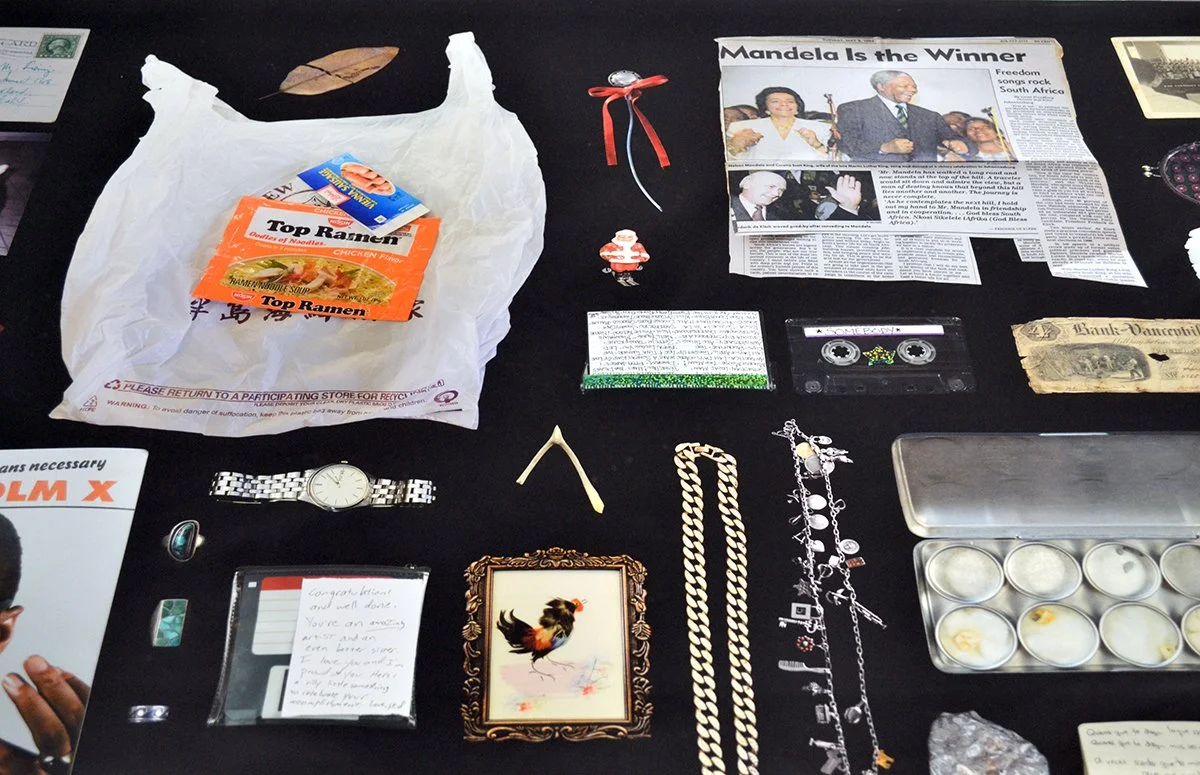

A detail view of Kija Lucas’s The Museum of Sentimental Taxonomy Vitrine #12, 2014–2025, archival pigment print. Image by Paloma Jimenez.

Nearby, Kija Lucas’s print of assorted sentimental objects at first resembles a flat curio cabinet. It’s filled with items ranging from a crumpled Top Ramen® package to a key, jewelry, and a seashell. Titled The Museum of Sentimental Taxonomy, Vitrine #12, the work, like the ghostly objects from Black Cube’s collection, reads as sacred. The printed objects are too precious to display fully, with the artist allowing only traces to be seen. Through pigment and paper, Lucas preserves moments from her own memory, capturing fragments of time and shielding them behind glass. These objects, though printed, dramatically halt the passage of time and spark memory.

An installation view of Cristóbal Gracia’s Perla barroca cultivada, “La Absoluta” / Baroque cultured pearl, “Assoluta”, 2025, brass, iron, plaster, and mixed media. Image by Third Dune Productions, courtesy of the artist and Black Cube Nomadic Art Museum.

Another weighty work, Cristóbal Gracia’s Perla Barroca Cultivada, “La Absoluta”, draws on the natural process by which a mollusk produces pearls: a small irritant enters the shell, and the animal secretes protective layers to encase it, enduring pain to create a prized object. The longer the mollusk endures, the more likely it is to form a baroque pearl—an irregular, uniquely shaped object unlike its round counterpart. [5] Gracia mirrors this process, ritualistically crafting a baroque, pearl–like form from thousands of small commodities: toys, audio tape, jewelry, and secondhand items sourced from Mexico City markets.

A detail view of Cristóbal Gracia’s Perla barroca cultivada, “La Absoluta” / Baroque cultured pearl, “Assoluta”, 2025, brass, iron, plaster, and mixed media. Image by Paloma Jimenez.

The work layers memory into its form: each object carries traces of past lives, embedded into a singular baroque pearl. These are objects we have let go of, either because we can no longer hold them or because they are no longer needed. The sculpture rests on a pedestal shaped like an oyster or mollusk trap, anchoring the work in a form designed to capture the creature for its eventual death.

Laleh Mehran, What the Air Carries, 2025, multimedia sculpture, commissioned for the What We Hold On To exhibition. Image by Third Dune Productions, courtesy of Black Cube Nomadic Art Museum.

A detail view of Laleh Mehran’s What the Air Carries, 2025, multimedia sculpture. Image by Paloma Jimenez.

On the exterior of the shelves, memory manifests both in tradition and ritual in Laleh Mehran’s What the Air Carries. The work centers on a traditional Persian tea set, accompanied by an audio track of children playing and other voices speaking Farsi and English, layered with the clinking of glasses in use. [6] Memory is reanimated through these traditional practices, such as the act of serving tea. At the same time, memory is transgressive here—blurring borders, bridging cultures, and erasing the boundaries of time.

An installation view of Phillip Andrew Lewis and Heather Dewey-Hagborg’s Spirit Molecule IV, 2025, petri dishes, medicinal plant samples, grow light, and 5-channel video, commissioned for the What We Hold On To exhibition. Image by Third Dune Productions, courtesy of Black Cube Nomadic Art Museum.

A video work also on the exterior of the shelves by Phillip Andrew Lewis and Heather Dewey-Hagborg provides a visual respite in an exhibition otherwise dominated by sculpture and installation. In Lewis and Dewey-Hagborg’s Spirit Molecule IV, the artists pair a five-channel video with plant specimens housed in petri dishes. The screens depict hands touching plants as well as people undergoing cheek swabs, evoking the methods of medical study or scientific analysis. The petri-dish plants reinforce the imagery onscreen, suggesting the artists’ efforts to research, preserve, or archive these specimens for a future in which they may no longer exist.

An installation view of the What We Hold On To exhibition at Black Cube Headquarters. Image by Paloma Jimenez.

Together, the works in What We Hold On To inspire meditation on memory, loss, and preservation. From the monumental to the intimate and tactile, each artwork engages with how objects, rituals, and images carry traces of personal and collective histories. The exhibition transforms Black Cube’s headquarters into a space where the past is both tangible and elusive, where memory can be celebrated, examined, and questioned. Ultimately, the exhibition asks us to consider what we choose to hold onto, who decides what we can hold, and how remembering shapes both individual and shared experience.

Dani/elle Cunningham (she/her) is an artist, scholar, and independent curator. She writes about science fiction, gender, sexuality, and disability, with an emphasis on mental illness. The co-founder of chant cooperative, an artist co-op, she holds a master’s degree in art history and museum studies from the University of Denver.

[1] From Courtney Lane Stell’s “Curatorial Framing” in the exhibition booklet.

[2] An excerpt from Walter Benjamin's The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction appears on the title card for Marek Wolfryd’s Content Creation in the Age of Globalized Reproduction. See docs.google.com/document/d/1fdtee9tSoArZvp6MZvOxUrSL-c1hCEnSjpLzZ6e56wQ?tab=t.0 for the full text.

[3] From the exhibition booklet.

[4] From my conversation with Kristi Zaragoza, Operations and Engagement Manager of Black Cube, September 14, 2025.

[5] From the exhibition booklet.

[6] Ibid.