Beyond Resilience

Beyond Resilience

Museum of Art Fort Collins

201 S. College Avenue, Fort Collins, CO 80524

June 27–September 14, 2025

Curated by Hamidah Glasgow

Admission: Adults: $10.00, Students: $8.00, Seniors (65 and up): $8.00, Under 18: free

Review by Maggie Sava

As a sign in the Museum of Art Fort Collins informs visitors, the exhibition Beyond Resilience includes works that “contain imagery and themes related to trauma, gender-based violence, and systemic oppression.” This review discusses these works and themes, which may be sensitive topics or difficult for some readers.

In her essay “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House,” Audre Lorde astutely articulates how constantly having to educate about or defend one’s existence to the powers that be as a person with a marginalized identity, is, “an old and primary tool of all oppressors to keep the oppressed occupied with the master’s concerns.” [1] Through her intersectional feminist analysis, Lorde argues that operating within oppressive systems actively takes resources away from us. Constant resilience is exhausting, and the exhaustion is purposeful. What happens when our mental, emotional, and physical resources are depleted? What is left to fuel creative acts?

An installation view of Beyond Resilience at the Museum of Art Fort Collins. Image by Maggie Sava.

Beyond Resilience adopts a political and feminist framework built from a similar line of inquiry. What if we don’t want to be celebrated for staying strong in patriarchal systems while mechanisms of oppression and harm remain in motion? What if we want to find a way to exist outside of them?

Curated by Hamidah Glasgow and featuring the work of Mona Bozorgi, Odette England, Melissa Grace Kreider, Marcy Palmer, Danielle SeeWalker, and Shuyuan Zhou, Beyond Resilience draws from current events, politics, personal narratives, and cultural experiences to create a multivocal dialogue about the manifestations of patriarchy and what it might mean to seek a different way of coexisting and caring for one another.

An installation view of Beyond Resilience at the Museum of Art Fort Collins. Image by Maggie Sava.

Glasgow served as the executive director and curator for the Center for Fine Art Photography in Fort Collins for sixteen years. Her connection to the medium of photography is extensive and undergirds this exhibition, as all the works except for SeeWalker’s paintings are photography-based or include photographic interventions and elements. Between all of the artists, however, is a dynamic diversity of scale, style, subject matter, process, and medium.

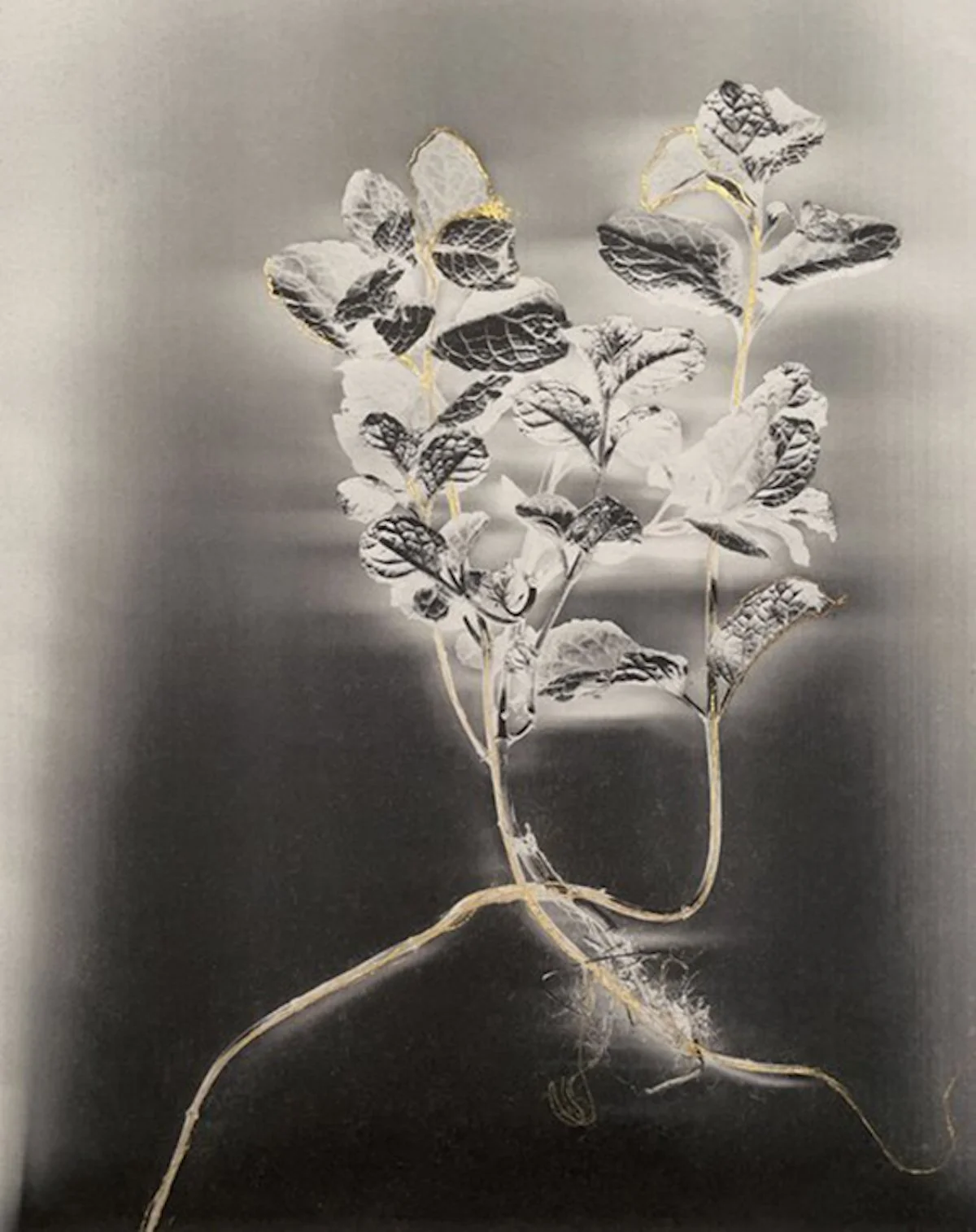

Marcy Palmer, Implant Release, 2025, toned cyanotype, 18k gold, varnish, and washi paper, 14 x 11 inches. Image courtesy of the Museum of Art Fort Collins.

In her Seeds of Strength and Resilience series, artist Marcy Palmer takes a unique approach to photographic exposure by using a phytogram process, where plants leave their images behind by seeping chemicals onto the paper, to make botanical abortifacients that are both the subject and chemical developer of her photographs. [2] The resulting layers of context between medium, creation, and subject matter highlight Palmer’s deliberate methodology and her attention to a compelling and timely narrative.

Marcy Palmer, Mentha, 2025, archival ink, 24k gold, and kozo paper, 14 x 11 inches. Image courtesy of the Museum of Art Fort Collins.

In the ethereal and eerie Mentha, Palmer depicts mint floating in a white, black, and gray space. Parts of the plant are delicately outlined in 24k gold, which the artist uses to signify hope, and the kozo paper on which she prints the image of the mint serves as a metaphor for women in its simultaneous delicacy and strength. [3]

Marcy Palmer, Beware, Beware, Keep Your Garden Fair, 2025, archival ink, 24k gold, and kozo paper, 14 x 11 inches framed. Image courtesy of the Museum of Art Fort Collins.

While historic uses of these plants show that abortions have always occurred and will continue to occur, Palmer reminds viewers that botanical abortifacients are not a safe or reliable means for terminating a pregnancy. In the current political climate, where Roe v. Wade has been overturned and reproductive rights are under siege, her work asks: What if we chose to keep people with uteruses safe by reinstating and codifying the right to access this important form of healthcare?

An installation view with works by Danielle SeeWalker in Beyond Resilience at the Museum of Art Fort Collins. Image by Maggie Sava.

Danielle SeeWalker’s canvases, which counterbalance Palmer’s prints with their size and vivid colors, address another pervasive issue, one that has long impacted Indigenous communities in the United States and Canada: Missing & Murdered Indigenous Relatives (MMIR). [4] MMIR is a systemic crisis in which Indigenous people, especially women and LGBTQIA2S+ people, experience violence at a highly disproportionate rate. These crimes are exacerbated by mishandling, bias, and insufficient support on behalf of law enforcement, lack of media attention or skewed media representation, and the historical colonization and exploitation of Native communities, among other factors.

Danielle SeeWalker, LOST // Am I A Spirit Now?, 2024, acrylic, aerosol, and oil stick on canvas, 36 x 24 inches. Image courtesy of the Museum of Art Fort Collins.

In Lost and They Keep Trying to Erase Me, SeeWalker meditates on the unknown fates of loved ones who have gone missing and the lack of closure that comes from their liminal existence between the human realm and the spiritual realm. The figures in each painting face out towards the viewer, yet parts of their faces are obscured by blocks of black paint. Their exposed facial features are highly detailed, suggesting physicality, but SeeWalker depicts their hair and torsos in flat colors, making the rest of their forms seem otherworldly. With one uncovered hazel eye, the figure in They Keep Trying to Erase Me demands and holds the viewer’s gaze as if to claim, as the title suggests, place, presence, and endurance. We cannot look away from this important reminder of the loss of life and of loved community members.

Danielle SeeWalker, They Keep Trying to Erase Me, But It Won’t Work, 2025, acrylic, aerosol, and oil stick on canvas, 48 x 48 inches. Image by Maggie Sava.

As a Húŋkpapȟa Lakȟóta woman and citizen of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe in North Dakota, SeeWalker has been personally impacted by the MMIR crisis. She extends her work beyond the canvas as a founding member of the Missing & Murdered Indigenous Relatives Task Force of Colorado. [5]

Shuyuan Zhou, My Great Grandmother, My Grand Aunt, My Grandmother, My Mother and I #2, 2022, archival pigment print, 18 x 21 inches. Image courtesy of the Museum of Art Fort Collins.

While Shuyuan Zhou is at an earlier stage in her art career (the artworks listed on her website only date back to 2022), she holds her ground among the mid-career artists with the compelling compositions, use of color, and thematic exploration in her series My Great Grandmother, My Grand Aunt, My Grandmother, My Mother and I.

Shuyuan Zhou, My Great Grandmother, My Grand Aunt, My Grandmother, My Mother and I #1, 2022, archival pigment print, 18 x 21 inches. Image courtesy of the Museum of Art Fort Collins.

In these works, Zhou examines her family members’ intergenerational trauma created by the patriarchal social dynamics into which they were born and raised as women in China. In her artist statement, Zhou describes how the women in her family survived violence and abuse either by being forced to serve the men in their lives or, in the case of her grandmother, being raised as a boy during childhood. Some of these women, in turn, perpetuated harm. Some of the girls, including her mother’s sister, did not survive. [6]

Shuyuan Zhou, Grace, Orchid # 3, 2025, archival pigment print, 18 x 21 inches. Image courtesy of the Museum of Art Fort Collins.

Through her photography, Zhou looks at how creative work can shift paradigms and form new dynamics, or, as she says, “a new degree of reality.” [7] In conversation with the publication Bold Journey, Zhou describes how, by talking with her family members and making this series, she found “a means of repairing relationships.” [8] She respects each of the women's experiences and the hardship forced upon them while also, as the show aims to do, finding the ways that artmaking might help make something new, different, and imbued with more possibility.

Melissa Grace Kreider, Remnants, newspaper (count of 5), 2017, newsprint, 15.25 x 11.25 inches folded, 15.25 x 22.75 inches unfolded. Image by Maggie Sava.

Melissa Grace Kreider, Remnants, newspaper (count of 5), 2017, newsprint, 15.25 x 11.25 inches folded, 15.25 x 22.75 inches unfolded. Image by Maggie Sava.

Taking a more documentary approach in her photographs, Melissa Grace Kreider uses direct visual language and informative titles to expose the harsh realities of domestic violence and rape culture in the United States. In particular, her newspaper Remnants from 2017, which you can flip through in the gallery, shares shocking statistics about the prevalence of domestic and sexual violence. One spread in the newspaper shows what at first appears to be a quiet residence until you read the caption explaining that it is the location of a reported incident of domestic assault. Under the photo, the paper reads, “1 in 3 women and 1 in 4 men have been victims of physical violence by an intimate partner.”

Melissa Grace Kreider, 38 instances of domestic and sexual assault in August 2015, 2015, archival pigment print, 20 x 24 inches. Image courtesy of the Museum of Art Fort Collins.

Kreider’s work makes it clear that these forms of violence are unacceptably common, and even normalized, as in the seemingly unassuming picture of a housing unit that was actually the site of 38 instances of domestic and sexual assault in just one month alone.

Melissa Grace Kreider, 128 backlogged kits in this location, 2016, archival pigment print, 20 x 24 inches. Image courtesy of the Museum of Art Fort Collins.

In other photographs, she captures the number of untested rape kits at different crime investigation locations and reproduces the form that law enforcement officers use to gather information and evidence from victims. Kreider illuminates the painful experiences victims have when reporting these traumatic events to law enforcement officers, when, so often, no justice comes from it. While Kreider’s photographs are not graphic, they are still visceral and stomach-churning.

An installation view of Odette England’s work in Beyond Resilience at the Museum of Art Fort Collins. Image by Maggie Sava.

The exploration of different forms of gender-based violence continues in Odette England’s work. However, she turns her investigation back towards the act of photographing itself, drawing connections between men “shooting” nonconsensual photographs of women and the act of shooting guns. [9] England conducts this meta-analysis of the act of photographing through the collection and arrangement of found photographs. These show women covering their faces from unwanted pictures, hands reaching towards the women, and people aiming and shooting guns.

Odette England, Untitled, archival pigment print from found photograph, 15.5 x 20 inches. Image by Maggie Sava.

While someone hiding their face from a camera might seem mundane and innocuous, the way England places these images in conversation with one another highlights how the people being photographed are denied their agency and their desired privacy. The photos become horrifying, reminding us that yes, the (male) gaze can inflict harm, ranging from objectification to physical violence.

Odette England’s book Woman Wearing Ring Shields Face from Flash with a case of lipstick for writing in the book. Image by Maggie Sava.

A marked up page from Odette England’s book Woman Wearing Ring Shields Face from Flash. Image by Maggie Sava.

By including her book Woman Wearing Ring Shields Face from Flash in an interactive installation in which viewers can use red lipstick to mark up the pages, England involves her audience in the conversation so that they can actively reflect on these comparisons and what thoughts, words, feelings, and fears they inspire in us.

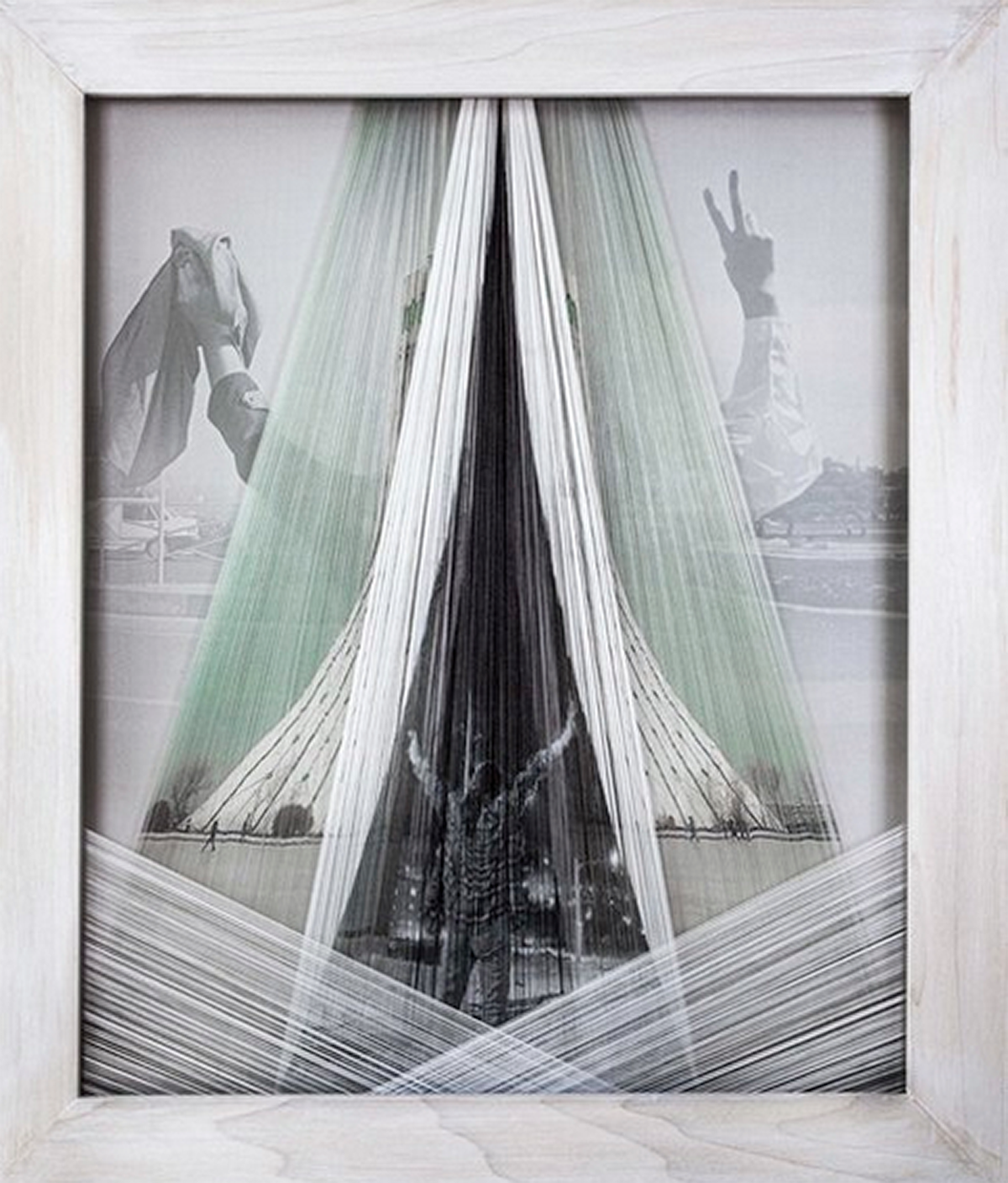

Mona Bozorgi, Unreclining, 2023, archival inkjet print on silk fabric (dismantled), 22.5 x 19.5 inches. Image courtesy of the Museum of Art Fort Collins.

Whereas England draws attention to the harmful side of photography, Mona Bozorgi engages with photography as an important political tool for Iranian women protesting oppressive laws controlling their bodies, specifically the pictures they have taken of themselves risking legal repercussions by removing and burning headscarves in public. Her textile photo prints are delicate, sculptural statements where carefully layered threads reveal empowering images of Iranian women. This is Bozorgi’s way of engaging with and supporting the cause while she herself cannot be in her home country. [10] The results are sizable, stunning, three-dimensional artworks that embody the time, effort, meticulousness, and care that Bozorgi put into them.

Mona Bozorgi, Fruits of Defiance: Eye, Liver, Shoulder, 2024, archival inkjet print on silk fabric (dismantled), 80 x 25 x 3 inches each (three pieces). Image by Maggie Sava.

Bozorgi describes her process as “a form of protest, a way to resonate with the struggle, to participate by reweaving our stories, and in so doing, amplify the significance of Iranian women’s actions and to echo their message… I carefully separate the threads to dismantle the fabric to reveal or cover the bodies and spaces, and to redefine traditional entanglements between women, fabric, and representation.” [11]

Mona Bozorgi, Wreath, 2024, archival inkjet print on silk fabric (dismantled), 83 x 83 inches. Image by Maggie Sava.

As with other artists in the show, the process of creation is part of the resonance and significance of her works. The action of artmaking connects her, and other artists, to families, communities, and the stories of so many others who have been impacted by the forces examined in each of the artworks. Wreath, Bozorgi’s kaleidoscopic installation piece, visualizes this connection by showing different women and families on each branch coming together to form a larger, shared tapestry across time and place.

Mona Bozorgi, Wreath (detail), 2024, archival inkjet print on silk fabric (dismantled), 83 x 83 inches. Image by Maggie Sava.

This desire to connect through art, not just alongside one another but because of one another, reminds me of Lorde’s statement that, “Interdependency between women is the way to a freedom which allows the I to be, not in order to be used, but in order to be creative.” [12]

An installation view of Beyond Resilience at the Museum of Art Fort Collins. Image by Maggie Sava.

While Glasgow herself recognizes that Beyond Resilience does not offer solutions to these engrained, institutionalized, and systemic forces (a tall order for a single exhibition), it does bring together a powerful conversation between artists who share an urgency to make a statement [13] It also shows how storytelling is both an essential means to bear witness and a way to begin the necessary work of imagining something different. One attendee phrased it very well in the gallery’s guest book: “They speak where there are no words.” While the works in this show will stop you in your tracks, they might also encourage you to find ways to keep stepping forward.

Maggie Sava (she/her) is an art historian and writer based in Denver. She holds a BA in art history and English, creative writing from the University of Denver and an MA in contemporary art theory from Goldsmiths, University of London.

[1] Audre Lorde, “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House,” in The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House (Penguin Random House UK, 2018), 20.

[2] Marcy Palmer, artist statement, Beyond Resilience, Museum of Art Fort Collins, Fort Collins, Colorado.

[3] Ibid.

[4] This is connected to the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls movements, but, as the name implies, it includes cases related to any Indigenous person rather than just cases involving women or girls. Referencing a 2016 study by the National Institute of Justice, the U.S. Department of Interior Bureau of Indian Affairs website reports that “more than four in five American Indian and Alaska Native women (84.3 percent) have experienced violence in their lifetime, including 56.1 percent who have experienced sexual violence.” “Missing and Murdered Indigenous People Crisis,” U.S. Department of the Interior Indian Affairs, accessed August 14, 2025, https://www.bia.gov/service/mmu/missing-and-murdered-indigenous-people-crisis.

[5] You can learn more about this taskforce on their website: https://mmirtaskforceco.com/.

[6] Shuyuan Zhou, artist statement, Beyond Resilience, Museum of Art Fort Collins, Fort Collins, Colorado.

[7] Ibid.

[8] “Meet Shuyuan Zhou,” Bold Journey, March 26, 2025, https://boldjourney.com/meet-shuyuan-zhou/.

[9] Odette England, artist statement, Beyond Resilience, Museum of Art Fort Collins, Fort Collins, Colorado.

[10] Mona Bozorgi, artist statement, Beyond Resilience, Museum of Art Fort Collins, Fort Collins, Colorado.

[11] Mona Bozorgi, “Threads of Freedom: Unweaving/Reweaving Representation” Art Journal Open, August 3, 2023, https://artjournal.collegeart.org/?p=18242&fbclid=IwAR2Sh71hRaRx3xkQH4Z2SDhETVuT13-UE7HCVdCCIlC8K5uqtCRw0Xf6wrg.

[12] Lorde, “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House,” 17.

[13] Hamidah Glasgow, “Beyond Resilience,” interviewed by Marcy Palmer, LENSCRATCH, July 9, 2025, https://lenscratch.com/2025/07/hamidah-glasgow-beyond-resilience/?fbclid=IwQ0xDSwLfJgBleHRuA2FlbQIxMQABHjcLJwDp9eNQPff3IQs-DgEVl7Bnc7rgOKs0ha-RDkWRfwya_lIpDTMKkgpb_aem_lLMaPz86Qx72-G7douQieA.