Exploring Water Through Art

Exploring Water Through Art

National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) Mesa Lab

3090 Center Green Drive, Boulder, CO 80301

May 9–October 8, 2025

Jurors: The Friends of the National Center, the UCAR Center for Science Education, and the Museum of Boulder

Admission: free

Review by Laura I. Miller

Water in Colorado is a prayer and a paradox. It gathers in high-altitude lakes and rushes through canyons yet always feels like it might vanish. In a landlocked state defined by drought, it’s not surprising that many artists turn to water as their subject. At the National Center for Atmospheric Research’s Mesa Lab in Boulder, the exhibition Exploring Water Through Art unfolds like a long thank-you note. Whether solid, liquid, or gas, water is everywhere here: as blessing, as memory, and as contested resource.

An installation view of Exploring Water Through Art at the National Center for Atmospheric Research. Image by Laura I. Miller

Sheena Rae Dowling, Bathing Series #22, 2024, oil on canvas. Image by Laura I. Miller.

The show doesn’t shy away from complexity. Gratitude flows alongside grief. Awe is tempered by urgency. The best works tap into this tension, reminding us that while we depend on water for life, we have also imperiled it. In a gallery perched in a high-desert landscape, these pieces invite us to imagine water not just as inspiration, but as an interlocutor. If the exhibition has a thesis, it might be this: We are in constant conversation with water—and lately, we’ve been doing more talking than listening.

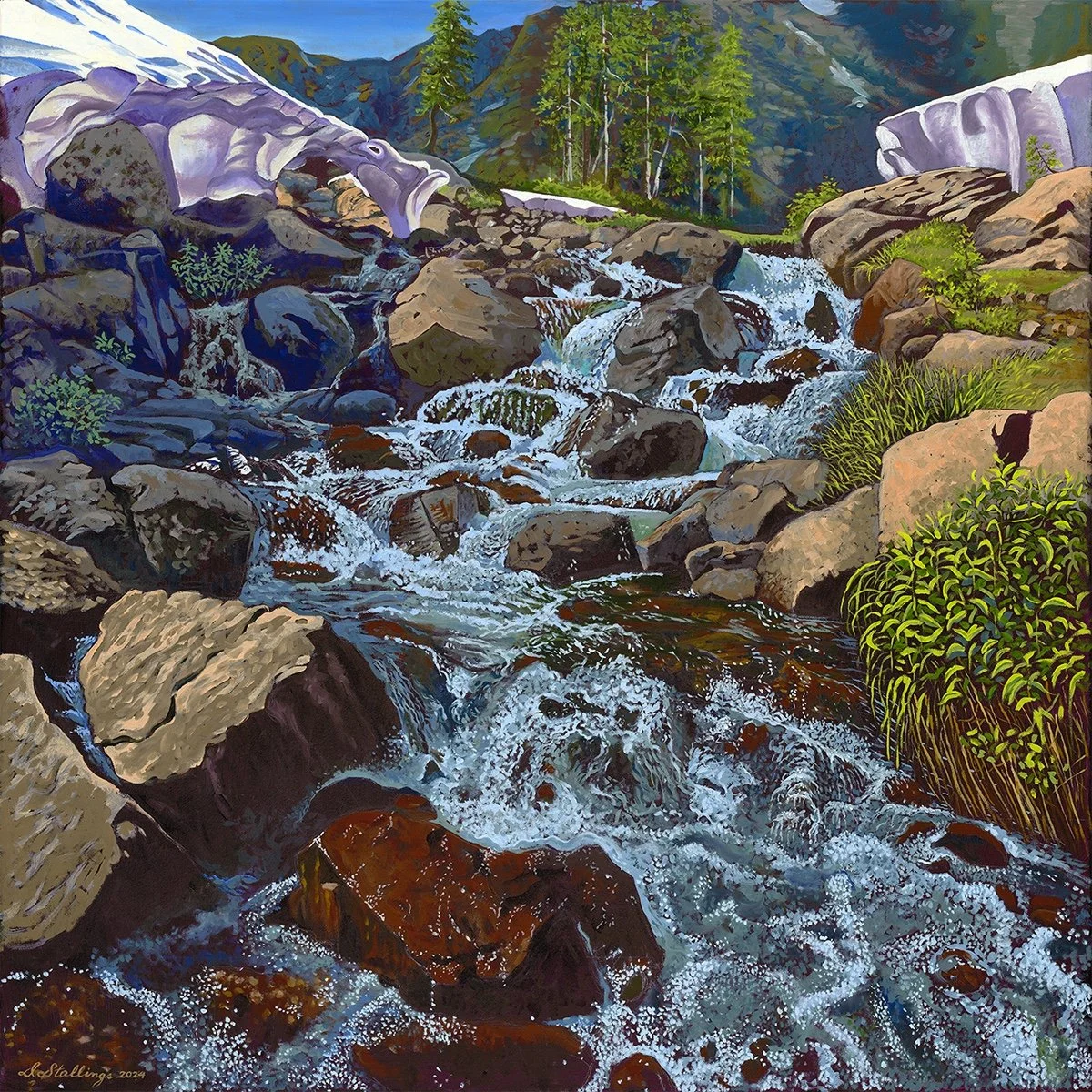

David Stallings, Just Below Upper Cataract Lake, Eagles Nest Wilderness, CO, 2024, oil on canvas. Image courtesy of the artist.

The most immediately striking through-line of the show is its romanticization of rivers, lakes, and waves. These works don’t just depict water, they adore it. In Just Below Upper Cataract Lake, Eagles Nest Wilderness, CO by David Stallings, you can almost feel the cool alpine air and the smooth surfaces of rocks warmed by the sun. The painting is a play between stillness and movement, capturing the rapids of the stream and the stoicism of the boulders and snow.

Allison O’Neall, Cresting Waves, 2025, merino wool and silk. Image by Laura I. Miller.

Similarly, Cresting Waves, a textile work made from wool and silk by Allison O’Neall, leans into motion, with the chaos of waves rendered in thick cloth. There's a drama to it, like standing at the edge of something that won't let you in.

Nancy Sullo, Free Falls, 2020, watercolor. Image courtesy of the artist.

But it’s Free Falls by Nancy Sullo that lingers longest. At first glance, it’s a cascade, perhaps a waterfall at sunrise. But the palette resists easy reading: pinks blush into crimson, the water’s flow rendered in tones closer to flesh than stone. The waterfall begins to feel less like a landscape and more like a series of arteries that pulse with corporeal color. It's a love letter to water, but also a meditation on mortality and on how the body's waters mirror the planet's.

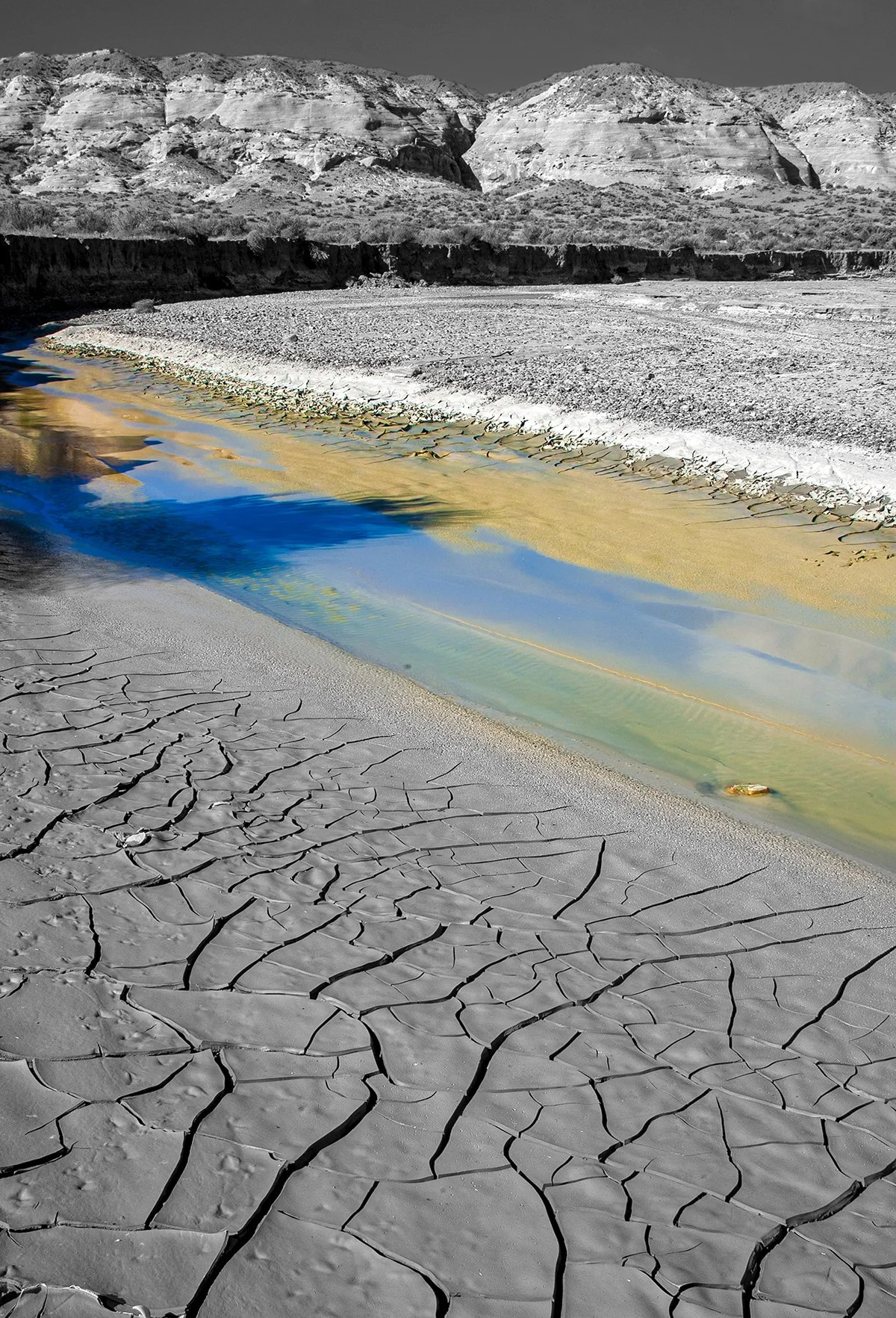

Brian Hooker, The Last River, 2021, archival pigment print photograph. Image courtesy of the artist.

The photographs on display, for the most part, refuse to romanticize. They document, witness, and warn. The Last River by Brian Hooker feels almost post-apocalyptic: it shows a cracked basin engulfing shallow pools that form the ghost of a river, suggesting that what once flowed will soon be no more. The color is spare, with only a thin strip of blue depicting a reflection of sky and clouds. It’s a reminder that reverence doesn’t stop depletion. In Tempest Rising by Steven McBride, the mood darkens. Waves churn under storm-heavy clouds and water becomes menacing—not life-giving, but threatening; not peace, but force.

Chris Parmelee, Community Pool, 2013, archival inkjet print photograph. Image by DARIA.

There are quieter moments, too. Community Pool by Chris Parmelee shows an urban basin surrounded by concrete and void of people, the pool’s water frozen into a chlorinated blue. The scene reminds us of how our relationship to water ebbs and flows with the seasons.

Stephanie Burkart, Fire and Ice, 2021, photograph printed on canvas. Image by Laura I. Miller.

Fire and Ice by Stephanie Burkart complicates our relationship with water further. The image—with smoke from the Marshall Fire rising in the background and water placid in the foreground—holds an eerie stillness. The fire is far off, but not far enough. The water is there but can’t help. The piece refuses easy narratives of salvation. Instead, it captures the powerlessness we sometimes feel in the face of crises. Water is present, but not always a protection.

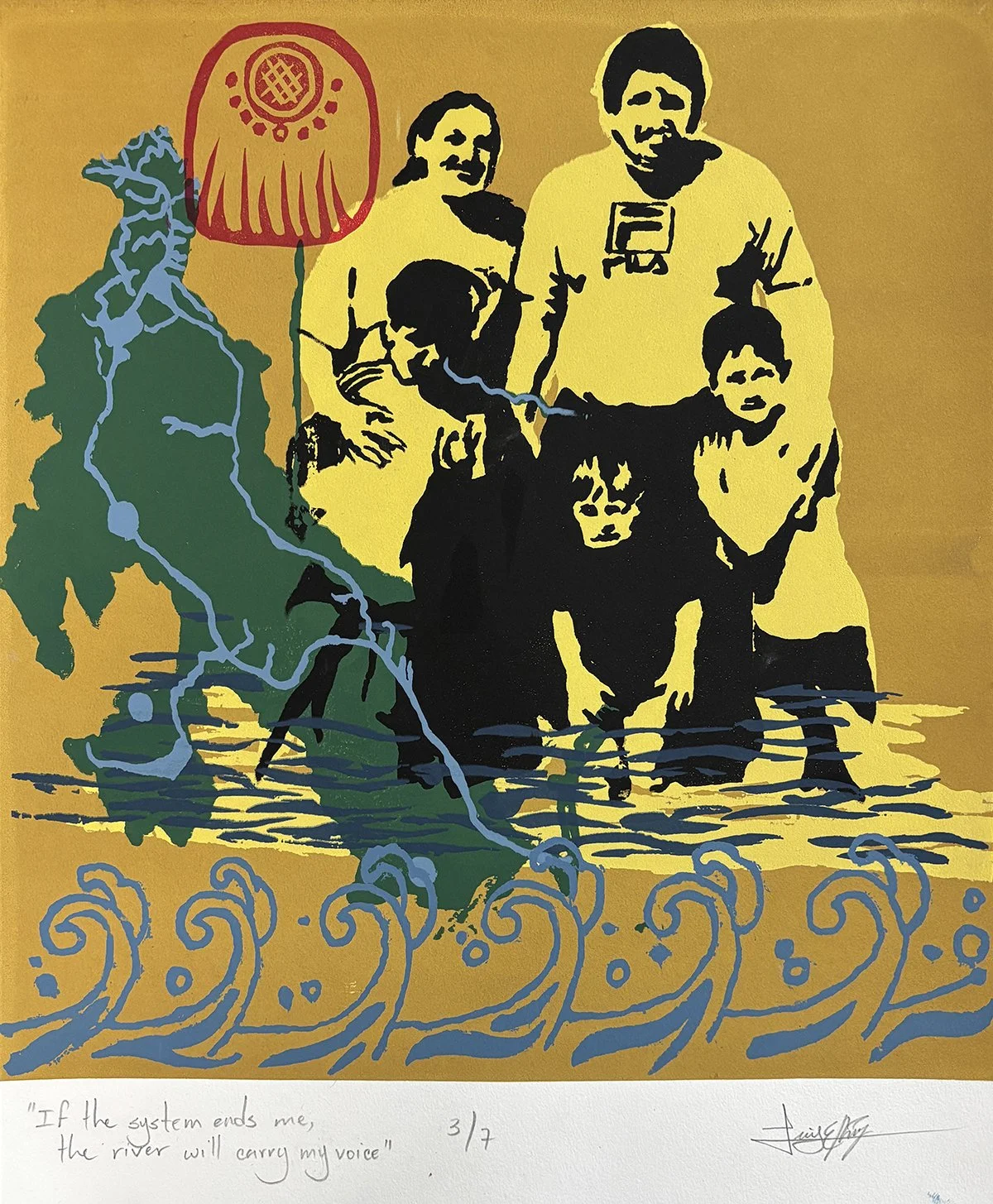

Luis Perez, If the system ends me the river will carry my voice, 2025, screenprint. Image courtesy of the artist.

With a few of the works, the exhibition veers into conceptual terrain, asking more questions than it answers. In Luis Perez’s If the system ends me the river will carry my voice, water becomes metaphor and medium. The title alone suggests legacy, survival, and erasure. The river here is not just a body of water—it’s a conduit, a keeper of memory. The piece insists that water is political; that its flow is shaped by borders and histories. There's longing in it, but also resistance, and a belief that the river might speak when systems fail to.

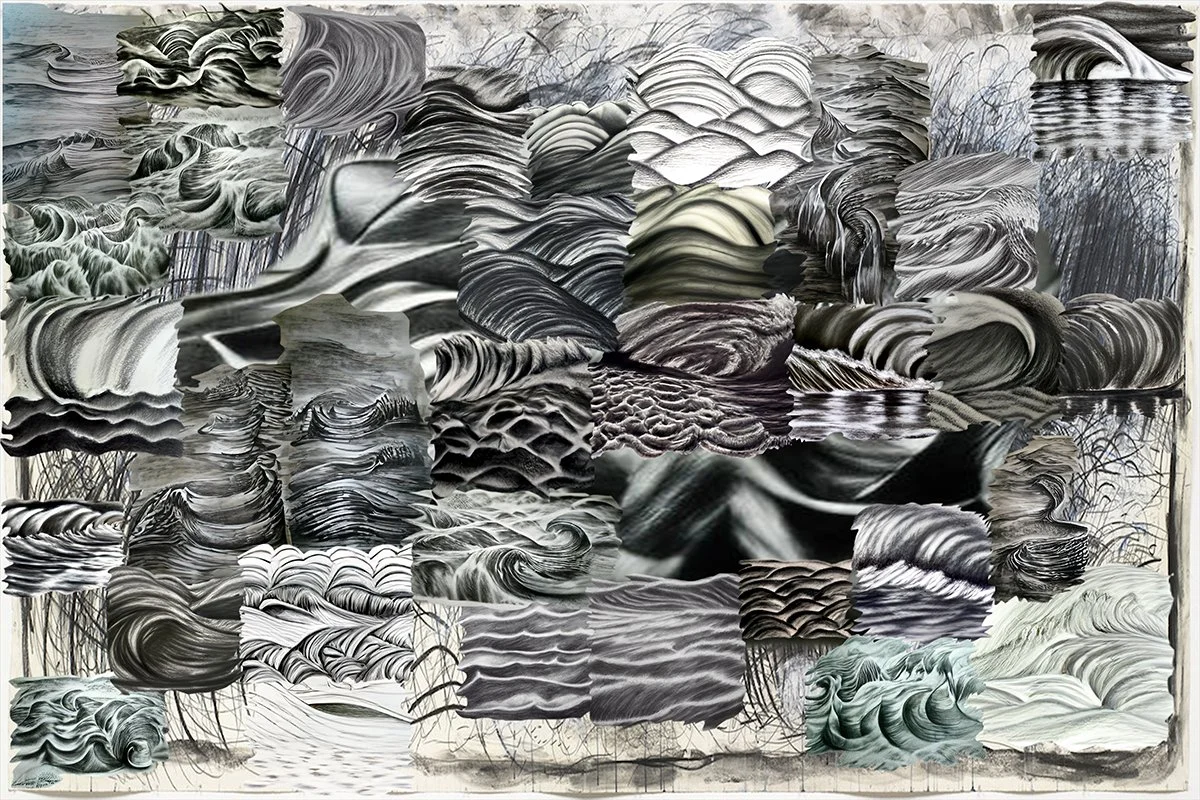

Noah Travis Phillips, high tide(s), two levels (Pat Steir "cover", GAN collage), photomechanical reproduction. Image courtesy of the artist.

Noah Travis Phillips's high tide(s), two levels (Pat Steir "cover", GAN collage) turns the tides into data. Using AI to reproduce wave patterns, the piece is less about nature and more about its simulation. What does it mean to create an ocean from code? The collage hints at deep questions about mediation and how technology relies on and distances us from the natural world. It’s strangely mesmerizing—the artificial waves look real, but what’s the environmental cost of their creation? Water here becomes a source of both power and anxiety.

Christian Suarez, Blue Heron, 2025, acrylic on canvas. Image by Laura I. Miller.

Two paintings carry the animal thread: Blue Heron by Christian Suarez and Koi Pond by Susan Skjei. In the first, a heron stands in profile, the river cutting into its legs. The brushstrokes are thick and angular, almost tribal, reminiscent of a folktale. The painting is striking in its severity but also emblematic—a bird that lives where water meets land, thriving in liminal zones.

Susan Skjei, Koi Pond, 2023, watercolor. Image courtesy of the artist.

Koi Pond, by contrast, is all color and ease. The fish swirls in lazy loops, a cluster of lily pads resting like clouds above. Both works evoke serenity, content to float on the surface.

William Stahl, Every River Tells a Story: Boulder Creek, 2025, wood burning and watercolor on bass wood. Image by Laura I. Miller.

But the surface is where this exhibition ends. There’s no dive, no depth. No kelp forests, no bioluminescence, no deep-sea creatures or pitch-black mystery. Exploring Water Through Art hints at water as habitat but does not explore it. We see what we can see from above. There’s a lack of plunging into the unknown—of acknowledging that water also resists, evades, and humbles us. The animal presence is gentle and dominated by humans. The exhibition offers a glimpse but fails to venture into the subterrain where human influence recedes.

Laura I. Miller (she/her) is a Denver-based writer and editor. Her articles, reviews, and short stories appear widely. She received an MFA in creative writing from the University of Arizona.