Maya Guatemala and Us: Divergent Convergences

Maya Guatemala and Us: Divergent Convergences

Gregory Allicar Museum of Art, Colorado State University

The Griffin Foundation Gallery

1400 Remington Street, Fort Collins, CO 80523

April 4–July 27, 2025

Curated by Dr. Robert W. Hoffert

Admission: Free

Review by Maggie Sava

In the current political landscape of the United States, which is increasingly shaped by rhetoric meant to define, moralize, and legislate differences to further disenfranchise historically marginalized communities, it is time that the assumptions underlying conversations about relationality shift. So much attention is given to what factors separate us from one another in order to form the qualifications for groups that “deserve” to belong and those that do not. What would happen if we began not just to examine similarities (we can still celebrate differences without having to criminalize them) but also the many ways our histories are truly intertwined and what forces continue to shape those stories?

An installation view of Maya Guatemala and Us: Divergent Convergences at the Gregory Allicar Museum of Art in Fort Collins. Image by Maggie Sava.

Maya Guatemala and Us: Divergent Convergences at the Gregory Allicar Museum of Art (GAMA) sets out to do just that, looking specifically at the legacy of colonization for the Maya peoples, the foreign interventions in the development of the Guatemalan nation, and how it continues to manifest in American politics and current events as the population of Guatemalan immigrants in the United States continues to grow. [1]

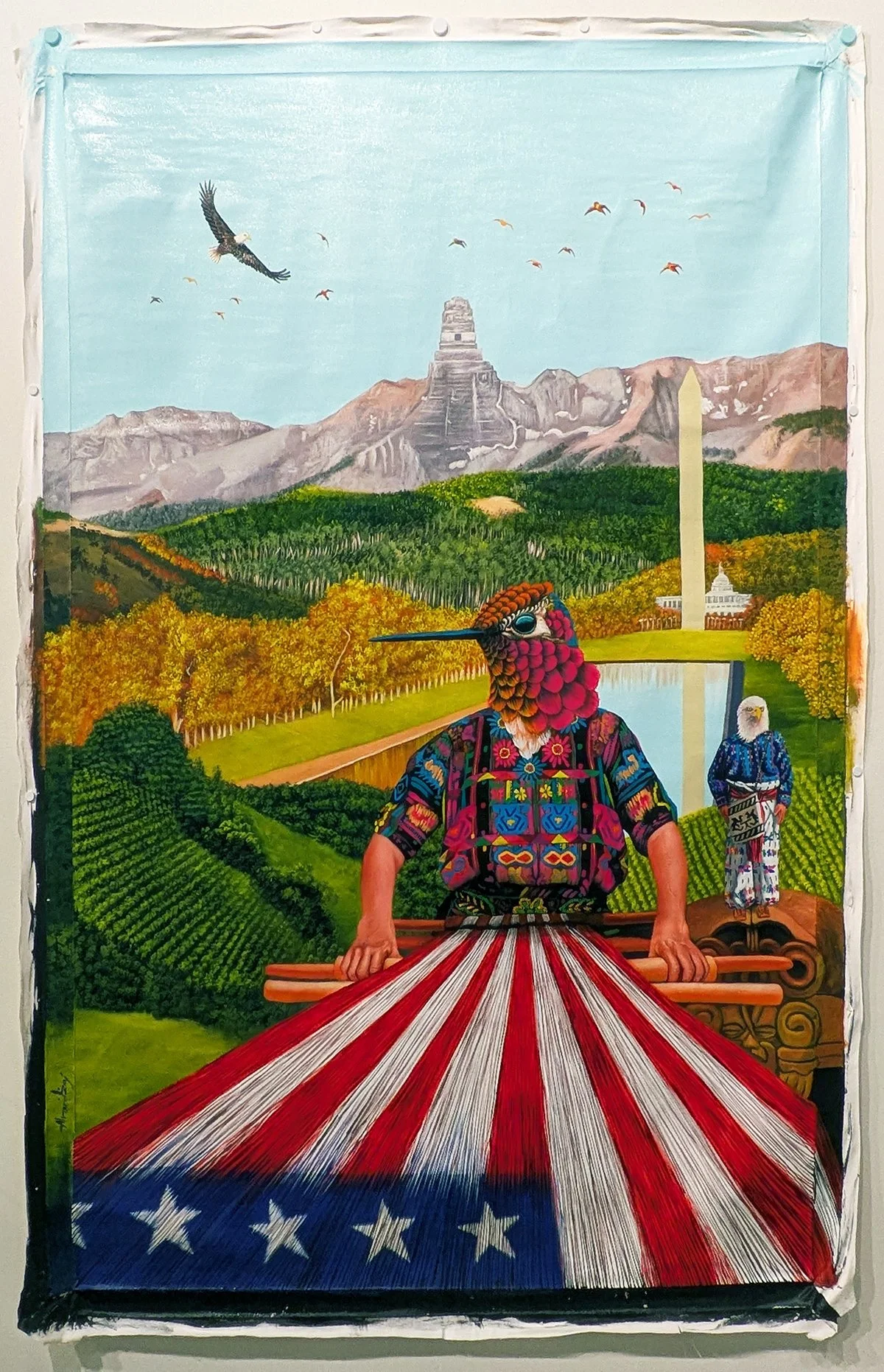

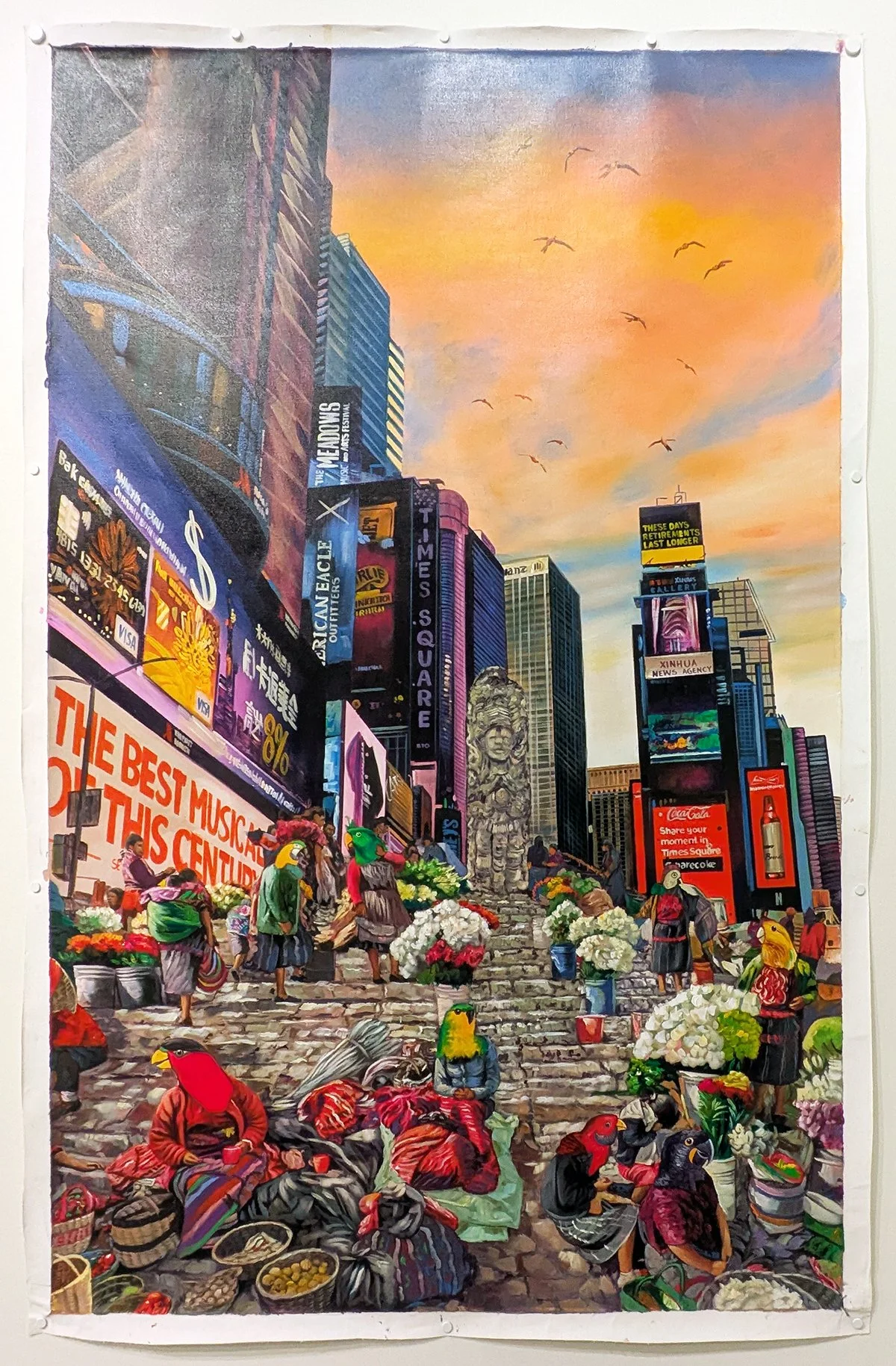

Alvaro Tzaj Yotz, WEave the People / Tejer al pueblo, 2023, oil on canvas. Image by Maggie Sava.

Organized into five distinct sections that act as a broad historical timeline, Maya Guatemala and Us conducts an aesthetic exploration of several centuries worth of Maya and Guatemalan history. All the sections, which could be entire exhibitions on their own with the complex themes they carry, are quite brief, providing more of a 101 survey or starting-off point, after which you can choose to deepen your knowledge independently. Dr. Robert W. Hoffert, curator of the exhibition and GAMA board member, narrows the focus of the show through the paintings and prints of four contemporary Guatemalan artists and woven textiles from the Avenir Museum of Design and Merchandising.

An installation view of Luis Rodas, Tz’utuii K’aslem (Woven Life), 2024, watercolor, ink, chalk, colored pencil, and pastels on paper with duct tape; Jun K’aslem (One Life), 2024, watercolor, ink, chalk, colored pencil, and pastels on paper with duct tape; and Ulew K’ayb’al (What Only Mother Earth Gives), 2024, watercolor, ink, chalk, colored pencil, and pastels on paper with duct tape. Image by Maggie Sava.

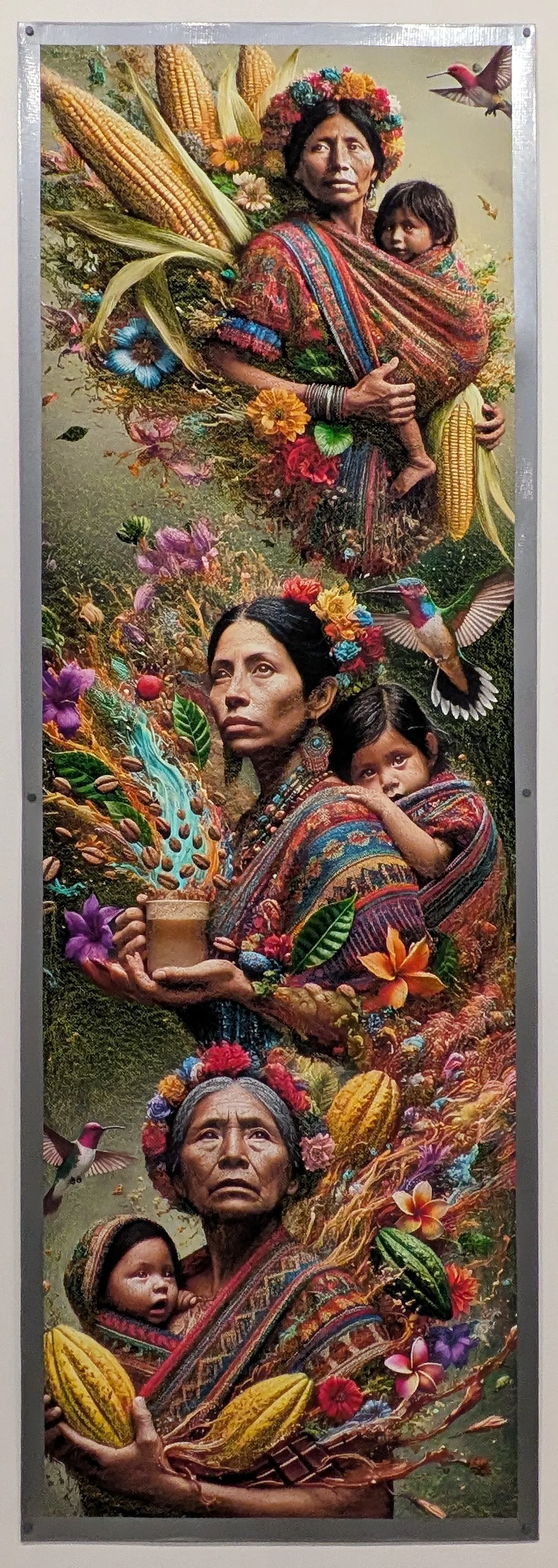

”Maya Life: Pre-Convergence,” as the name suggests, looks at the Maya civilization before the arrival of Spanish conquistadors. This section showcases the impressive, photo-realistic, multimedia works of Luis Rodas, which depict Maya women and children of different ages surrounded by cultural symbols like colorful birds, corn, and squash. These subjects are not set in specific landscapes or scenes; instead, Rodas places them in a liminal space outside of geography and time, emphasizing that they are representations of different generations of Maya people. The portraits are detailed, dignified, and dynamic, surrounded by explosive auras of colors.

Luis Rodas, Ulew K’ayb’al (What Only Mother Earth Gives), 2024, watercolor, ink, chalk, colored pencil, and pastels on paper with duct tape. Image by Maggie Sava.

The meticulousness and technical skill behind these intricate portraits are balanced by the duct tape frames Rodas employs as “a reminder of Maya vulnerability.” [2] At first, the presence of this shiny, overtly functional material seemed to starkly contrast with the rest of the work. I wondered if an unfinished or raw edge to the canvas might have served a similar purpose. As I reflected on and challenged my feelings around what I assumed was an anachronistic addition, I understood more how the duct tape conveys the sense that these are not just generalized, idealized images of the ancient Maya but representations of a culture that is still vibrant, celebrated, and resourceful. It also creates a connection to the exhibition as a whole, conveying the precarity the Maya people continue to face as a result of colonization.

Luis Rodas, Tz’utuii K’aslem (Woven Life), 2024, watercolor, ink, chalk, colored pencil, and pastels on paper with duct tape. Image by Maggie Sava.

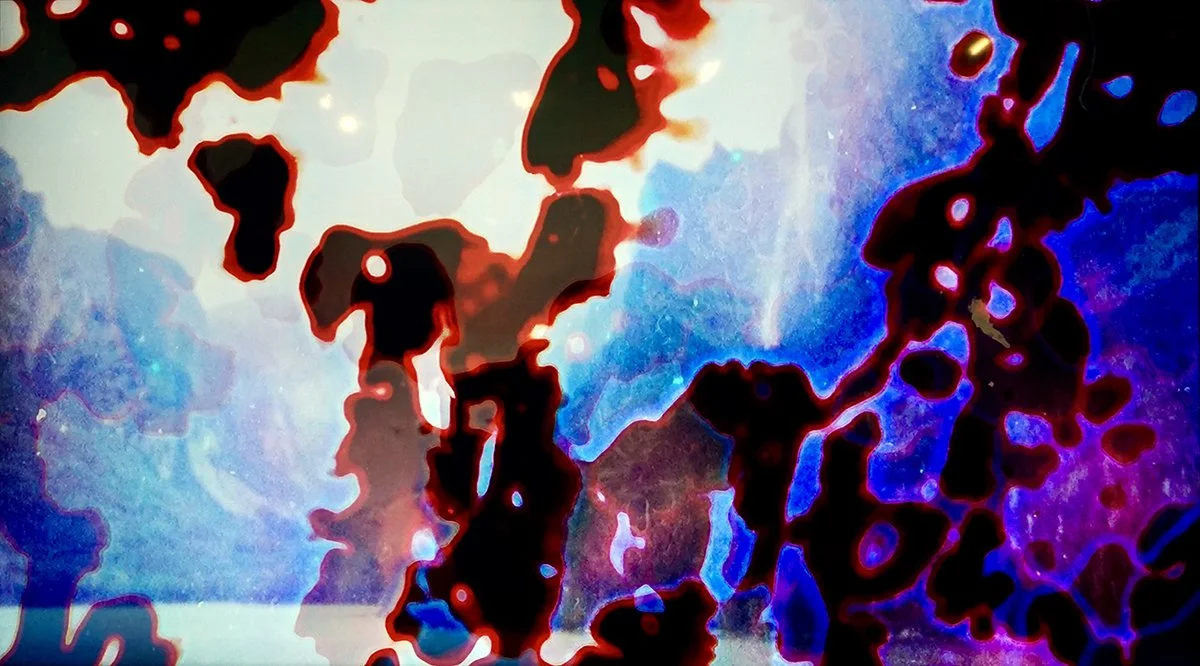

A detail view of Luis Rodas, Tz’utuii K’aslem (Woven Life), 2024, watercolor, ink, chalk, colored pencil, and pastels on paper with duct tape. Image by Maggie Sava.

At the bottom of Tz’utuii K’aslem (Woven Life), Rodas shows an older woman sitting at a loom, weaving. The movement of the fibers makes it seem as if she's creating more than just cloth. It appears that she is incorporating the elements and energy around her into a greater creation, demonstrating Hoffert’s statement that Maya people “wove art into the fabric of their lives and identities—brilliant colors, geometric-natural forms in a broad scope of applications.” [3]

Weaver Unidentified, Guatemala, Huipil Nebaj, undyed white cotton ground; multi color brocade figural motifs, on loan from Avenir Museum of Design and Merchandising, donated by Martha Egan. Image by Maggie Sava.

Weaver Unidentified, Guatemala, Huipil, blue ribbed cotton ground, black velvet sun motif at neckline, all over multi color zig zag brocade; purchased in Chichicastenango, on loan from Avenir Museum of Design and Merchandising, donated by Glenda Cowles. Image by Maggie Sava.

The art of weaving is a significant theme throughout this exhibition, showing not only Maya artistry but also how the cloths are both manifestations and symbols of the creation and endurance of Maya identity. The inclusion of woven huipils on loan from the Avenir Museum of Design and Merchandising provides material examples that highlight both the technical skills and rich design that goes into the color schemes and construction of these garments. Traditionally worn by women, huipils are specific to different Maya communities and are a visual indicator of which village or group someone is a member. [4]

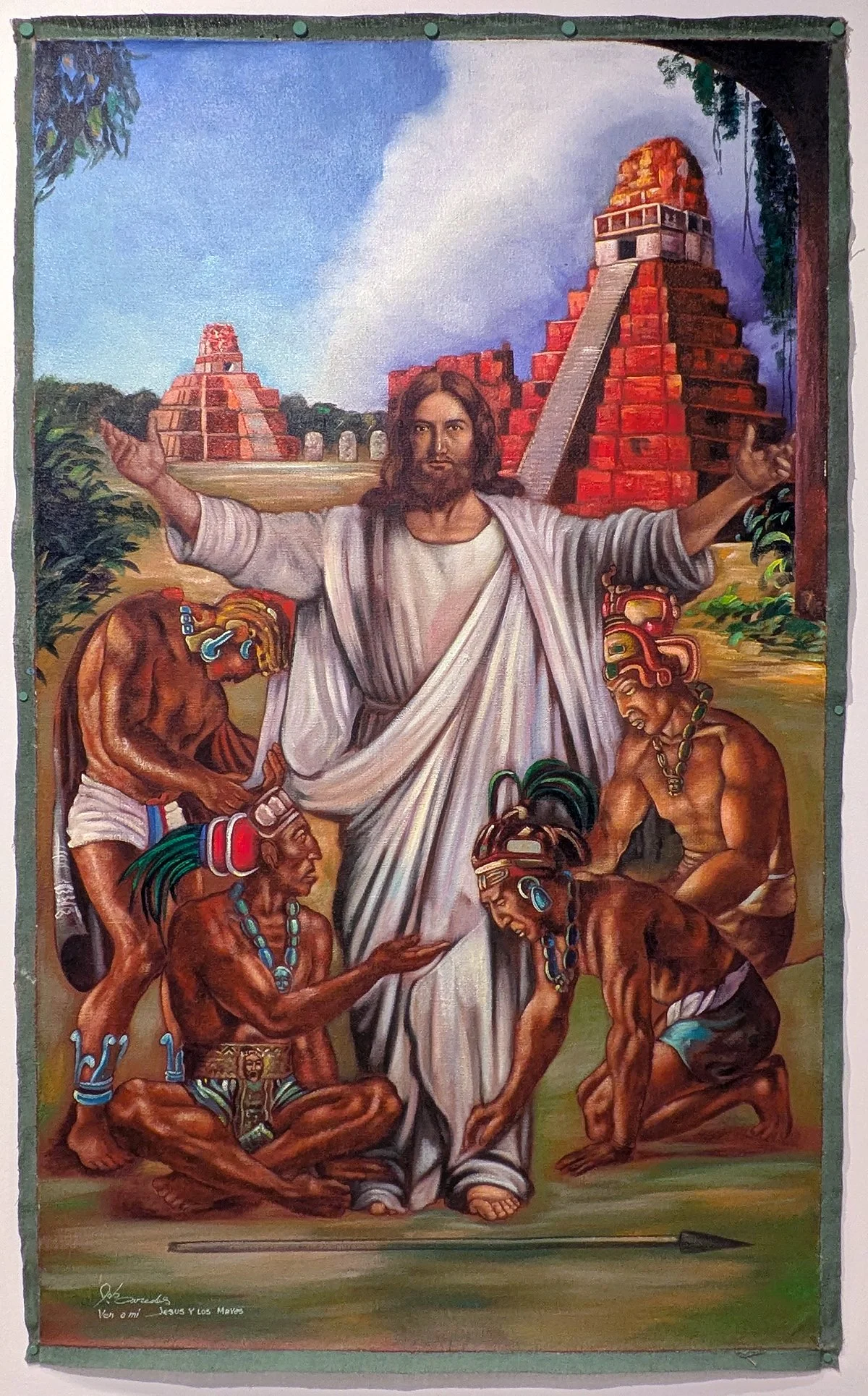

Job Paredes, Conquistador, 2023, oil on canvas. Image by Maggie Sava.

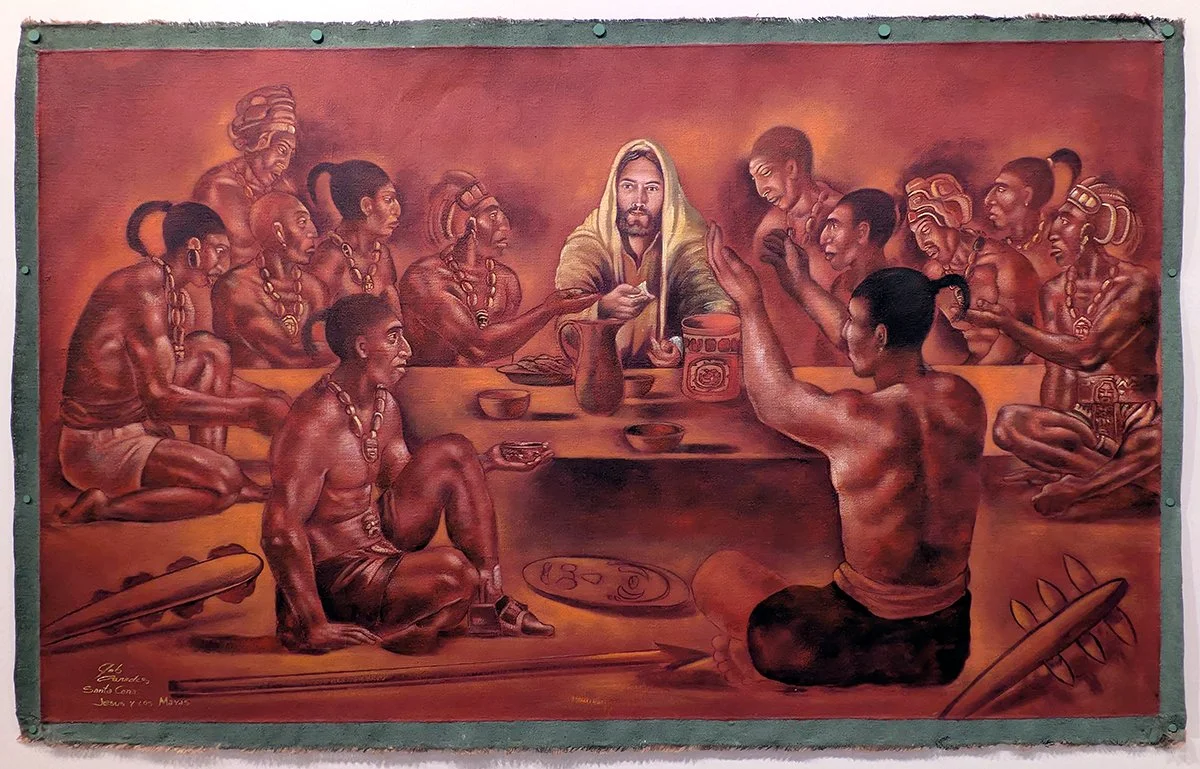

Two paintings by Job Paredes form the second section of the exhibition, “Divergent Convergence: ‘Discovery’ and Religion,” which tackles the Spanish use of Catholicism in the colonization of Maya peoples. In Conquistador, Paredes depicts a traditional image of Jesus as the central figure, standing in front of the architecture of an ancient Maya city. He is surrounded by people dressed in traditional Maya garments, with headdresses and intricate jewelry. [5]

Job Paredes, First Supper / Primera Cena, 2023, oil on canvas. Image by Maggie Sava.

The name of this painting suggests that Jesus is an imposing figure standing above the Maya figures, who are all positioned in reverent stances. Here, the Maya men exist in close proximity and connection to Jesus, as his disciples would be; however, teachings that Indigenous peoples were inferior to European settlers were used to assert ideas of racial and religious superiority, which in turn reinforced the oppression of the Maya peoples. The impact of the conversion of Indigenous peoples exists through the ongoing fusion and blending of Catholic rituals and teachings into traditional Maya religious practices. [6]

An installation view of Job Paredes, Banana Split, 2023, digital print on canvas; Peels So Good, 2023, digital print on canvas; We Are Bananas/ Somos plátanos, 2023, digital print on canvas; and 14 Cents a Pound / 14 centavos la libra, 2023, digital print on canvas. Image by Maggie Sava.

“Divergent Convergence: Land and Economic Power” and “Divergent Convergence: Ideology and Political Power” both explore what, at least for me, has been a less familiar (or, perhaps, less taught) history, one that implicates the United States in building off of colonial power structures for profit and political benefit. Tracing the control of land by wealthy Spanish settlers and the Roman Catholic Church to the insertion of American interest through the United Fruit Company, the exhibition texts describe how Guatemala’s economic and political development as a nation caused the continual disenfranchisement of Maya farmers. [7]

Job Paredes, We Are Bananas / Somos plátanos, 2023, digital print on canvas. Image by Maggie Sava.

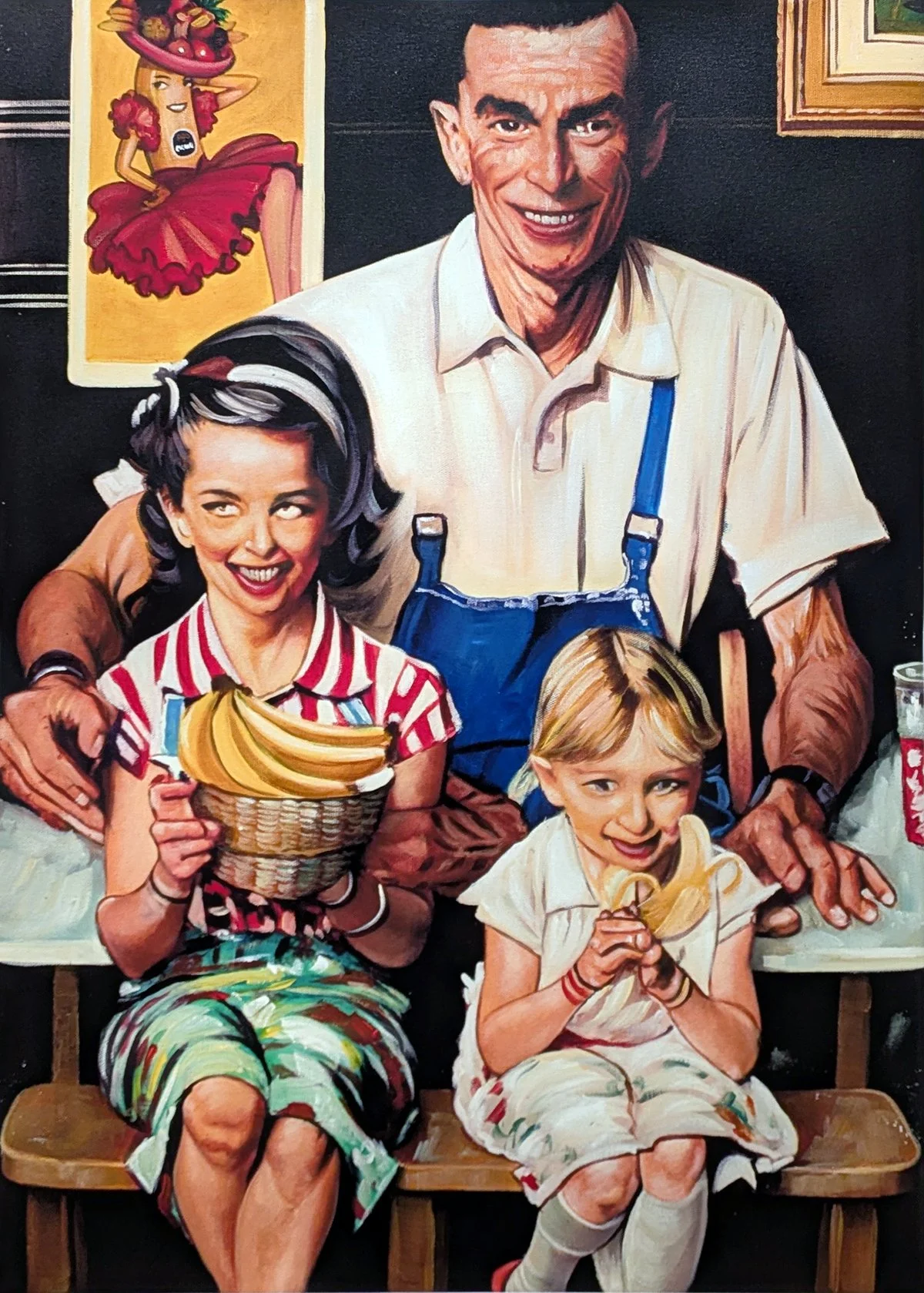

In this section, Paredes takes what seems like stereotypical, “all-American” images of happy families and transforms them into something more suspicious. I want to acknowledge that it is important to not view the unsettling nature of these images through ableism that others facial differences. When I was looking at these prints, I thought of the AI-generated images that have flooded the internet, in which it seems like the machine cannot create an actual human image and instead produces something within the uncanny valley. It seems like Paredes is trying to tap into a sense of irreality, which underscores the propaganda of the ideal American family and suggests that insidious forces perpetuate that image. Each print features a banana, and in We Are Bananas / Somos plátanos, a Chiquita banana poster hangs in the background, signifying the United Fruit Company's constant presence over these scenes.

Job Paredes, rioUSAmontt, 2023, oil on canvas. Image by Maggie Sava.

The exhibition continues the story of the United States’ interference with Guatemalan politics as it persisted through the nation’s civil war. As it had done in many other nations during the Cold War era, the United States exerted influence and force to advance political and economic interests, including through military intervention and coups, which led to long-term instability. The Maya people of Guatemala continued to face acts of state-sanctioned violence and oppression at the hands of presidents who were supported by the United States. [8]

An installation view of Edgar Fuentes, Because I Was Maya / Porque yo era maya, 2023, oil on canvas; Died Trying to Live / Murió intentando vivir, 2023, charcoal on canvas; Because I Too Am Maya / Porque yo también soy maya, 2023, charcoal on canvas; and Because I Am Maya / Porque soy maya, 2023, charcoal on canvas. Image by Maggie Sava.

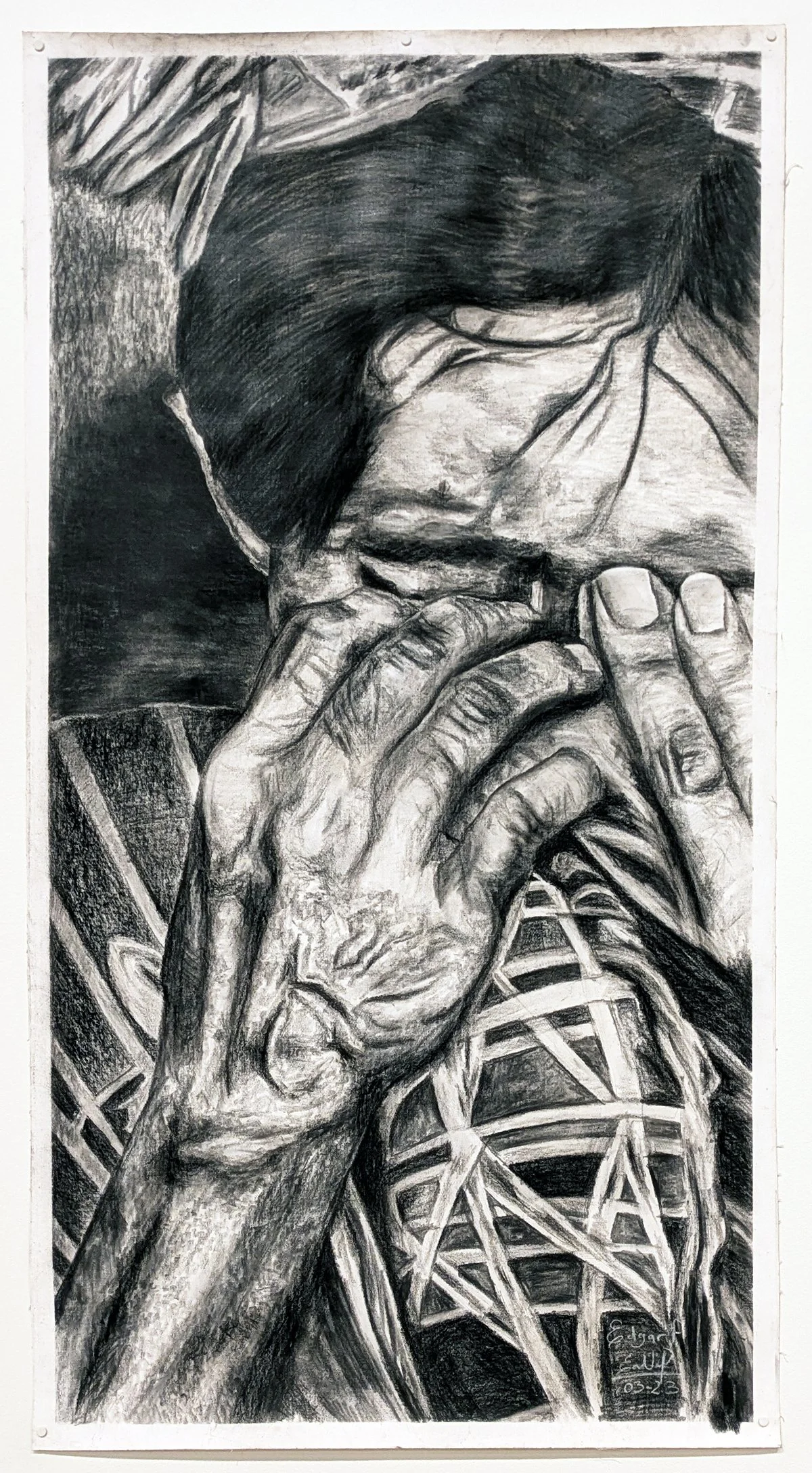

Edgar Fuentes’s series of canvases shows closely cropped, intimate, and evocative images of faces to convey the violence and trauma of political conflict. From weeping, distressed faces to a fighter pointing a gun to a skull in a helmet, Fuentes shows the stages and emotional and physical costs of warfare.

Edgar Fuentes, Because I Too Am Maya / Porque yo también soy maya, 2023, charcoal on canvas. Image by Maggie Sava.

The titles of the canvases—Because I Am Maya / Porque soy maya, Because I Too Am Maya / Porque yo también soy maya, Died Trying to Live / Murió intentando vivir, and Because I Was Maya / Porque yo era maya—convey that the Maya peoples have been the ones to carry a great burden and huge losses as a result of the internal and international conflicts over power and control in Guatemala.

An installation view of Maya Guatemala and Us: Divergent Convergences at the Gregory Allicar Museum of Art. Image by Maggie Sava.

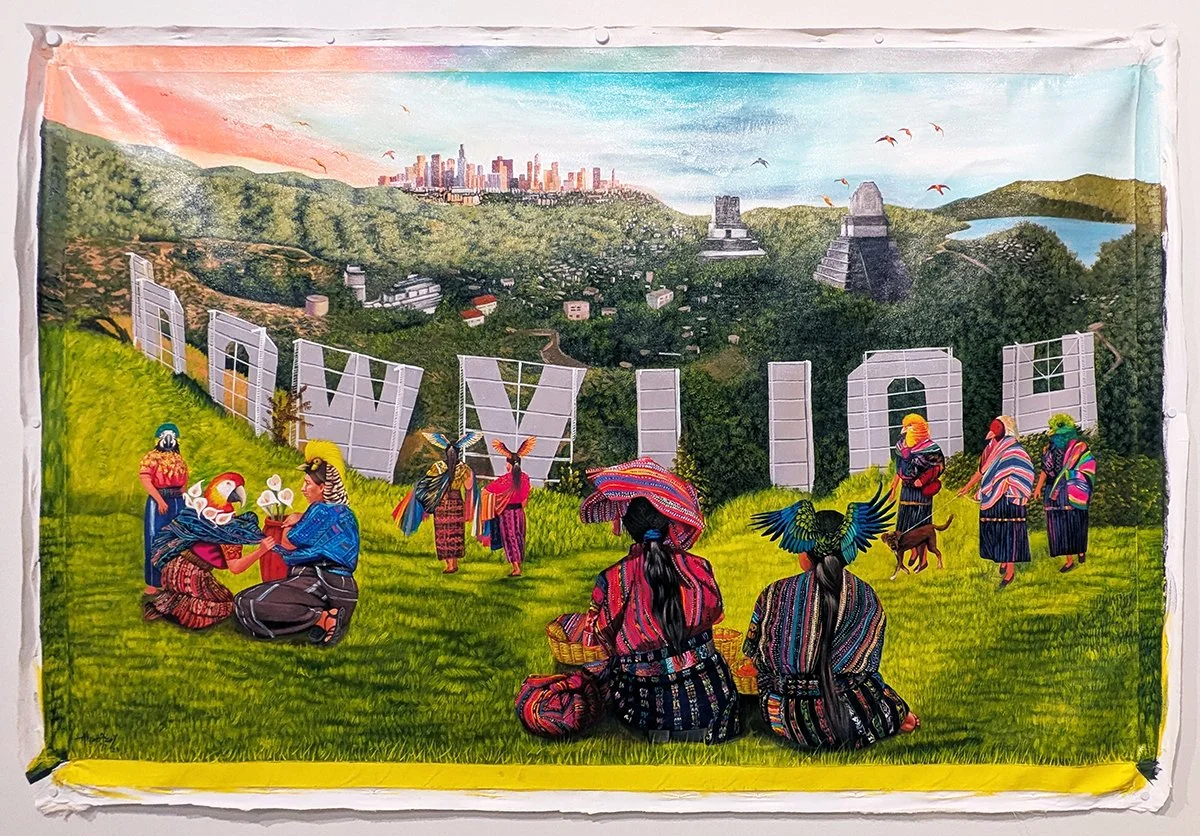

The final section of the show, “Divergent Convergence: Rejection and Hope,” is composed of Alvaro Tzaj Yotz’s vibrant paintings portraying famous American landmarks through a Maya perspective. Similar to Rodas, the use of vivid color and pattern, particularly through the clothing of his subjects, plays an important role in Yotz’s paintings. Yotz’s work also resonates with Paredes’s paintings in the “‘Discovery’ and Religion” section, as he too incorporates Maya architecture and cultural symbols into Euro-American imagery.

Alvaro Tzaj Yotz, Los MayAngeles, 2023, oil on canvas. Image by Maggie Sava.

As the exhibition text explains, this segment directs the historical narrative to the present day by connecting it to current trends in immigration, specifically that of Guatemalans to the United States in search of greater opportunity and economic mobility. [9] It is clear that the story unfolding throughout the gallery leads to this moment, in both direct and indirect ways.

Alvaro Tzaj Yotz, A New Colossus / Un nuevo coloso, 2023, oil on canvas. Image by Maggie Sava.

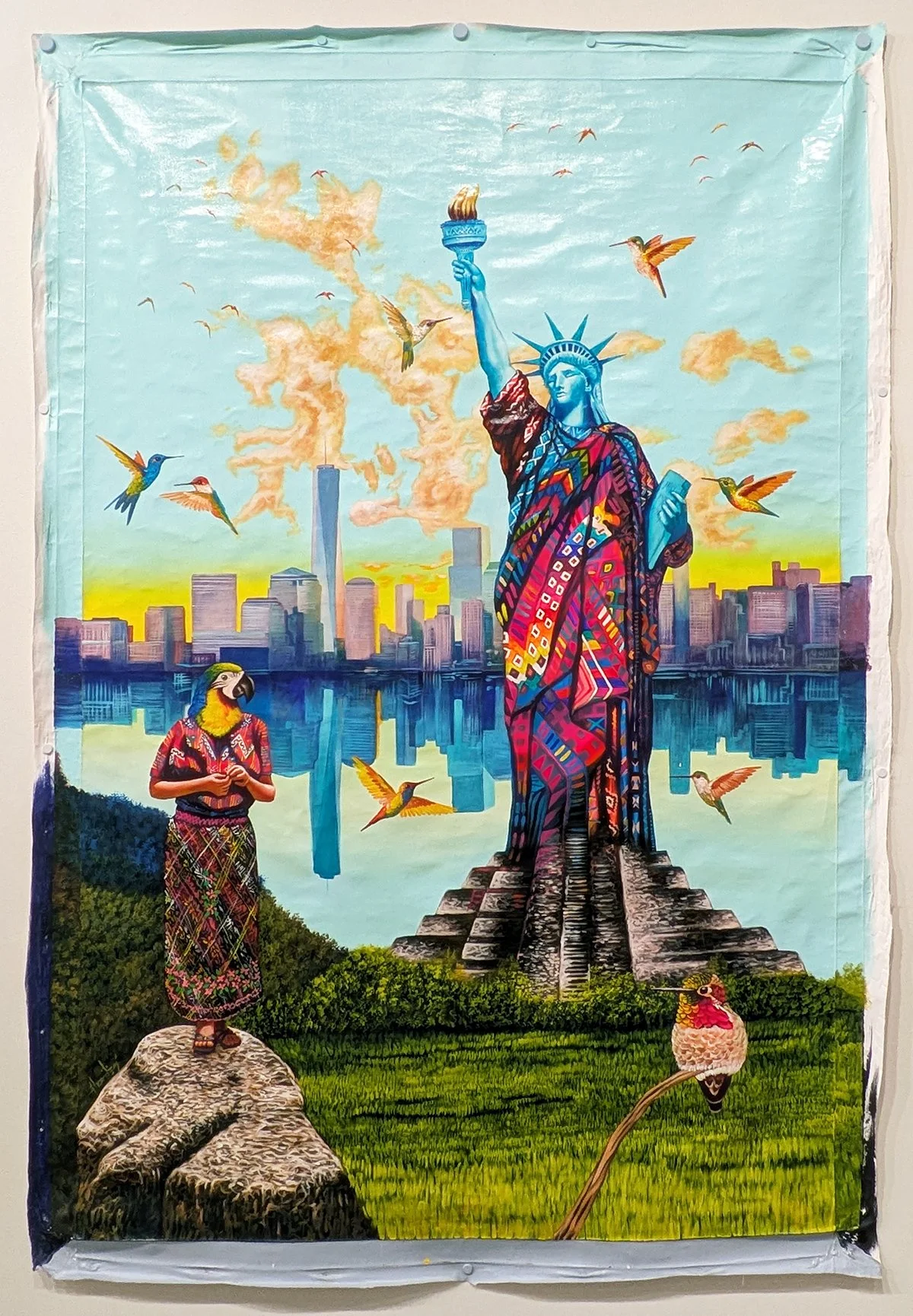

Emphasizing this connection, Yotz’s A New Colossus / Un nuevo coloso balances Paredes’ Conquistador on the opposite side of the gallery. Like Paredes, Yotz depicts a monumental figure—this time, the Statue of Liberty. The statue’s familiar flowing robes are replaced with bright, colorful woven Guatemalan fabrics. Hummingbirds hover around the statue, and in the bottom left foreground stands a bird-human hybrid, here representing a Maya person. The Statue of Liberty stands upon a stepped pyramid like those of ancient Maya cities.

Here, Yotz recontextualizes the symbolic image of the Statue of Liberty, meant to signify freedom and opportunity for incoming immigrants, in the specific hopes of Guatemalan immigrants. [10] He seems to offer a space in which Maya cultural identity is not just projected on, but integrated into, the American landscape.

Alvaro Tzaj Yotz, We Made It Here / Lo hicimos aquí, 2023, oil on canvas. Image by Maggie Sava.

As Hoffert points out, people generally immigrate to the United States with the hope that, by coming to America, they can participate in the so-called American Dream and improve their economic circumstances. That unfortunately is not the reality that many immigrants face. Instead, they are not just met with barriers, but often direct discrimination and animosity.

The exhibition text addresses the seemingly inexplicable “indifference of a nation to the pursuit of hopeful dreams by aspiring immigrants whose sufferings it directly, concretely, and substantially contributed.” [11] I would argue that it is no longer just indifference but direct hostility when we see raids, deportations that deny people their due legal process and protections, and other anti-immigrant actions happening around us.

A detail view of Alvaro Tzaj Yotz, We Made It Here / Lo hicimos aquí, 2023, oil on canvas. Image by Maggie Sava.

In the narrative unfolding throughout the exhibition texts and canvases, Maya Guatemala and Us inherently proposes an “us,” a group that the show is addressing. The “us” could simply be referring to the people who see the show. It could be those who share heritage with the European colonizers, or people who are unaware of these histories.

An installation view of Maya Guatemala and Us: Divergent Convergences at the Gregory Allicar Museum of Art. Image by Maggie Sava.

I find that a more effective read is that rather than trying to create an identifier in the “us,” we should see the exhibition title as an invitation to shift perspectives. We are encouraged to no longer view ourselves in isolation from others, and to no longer ignore the greater systems that bring us together, including the culpability and responsibility of different parties in those meetings and clashes. In turn, we cannot separate current events from the forces and factors that engendered them. Once we recognize those aspects of our collective histories, we may be able to listen, speak, act, and perhaps even legislate with the nuance and care that comes from knowing that we exist within an ongoing, complex relationality.

Maggie Sava (she/her) is an art historian and writer based in Denver. She holds a BA in art history and English, creative writing from the University of Denver and an MA in contemporary art theory from Goldsmiths, University of London.

[1] According to the Pew Research Center, “from 2000 to 2021, the Guatemalan-origin population [in the United States] increased 336%, growing from 410,00 to 1.8 million.” Mohamad Moslimani, Luis Noe-Bustamante, and Sono Shah, “Facts on Hispanics of Guatemalan origin in the United States, 2021,” Pew Research Center, August 16, 2023, https://www.pewresearch.org/race-and-ethnicity/fact-sheet/us-hispanics-facts-on-guatemalan-origin-latinos/.

[2] Gallery Exhibition Texts, Maya Guatemala and Us: Divergent Convergences, Gregory Allicar Museum of Art, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado, https://artmuseum.colostate.edu/events/maya-guatemala-and-us-exhibition-texts/.

[3] Extended Exhibition Texts, Maya Guatemala and Us: Divergent Convergences, Gregory Allicar Museum of Art, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado, https://artmuseum.colostate.edu/events/maya-guatemala-and-us-extended-exhibition-texts/.

[4] “Variation in Huipils,” Sam Noble Museum, accessed May 14, 2025, https://samnoblemuseum.ou.edu/collections-and-research/ethnology/mayan-textiles/pitzer-collection-of-mayan-textiles/regional-variation-in-huipils/.

[5] Clothing and accessories, including headdresses and jewelry, were important indicators of status and one’s role in society in the Mayan empire, especially for nobility. Lydia Pyne, “From Head to Toe in the Ancient Maya World,” Archaeology Magazine, July/August 2020, https://archaeology.org/collection/from-head-to-toe-in-the-ancient-maya-world/.

[6] Gallery Exhibition Texts.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] For an analysis of the motivating factors for Guatemalan immigration to the United States, see “Increased Guatemalan migration to U.S. border linked to agricultural stress, violence and climate change,” Duke Sanford Center for International Development, March 28, 2022, https://dcid.sanford.duke.edu/news/increased-guatemalan-migration-us-border-linked-agricultural-stress-violence-and-climate/. For more information about remittances—funds sent back to Guatemala by people working in the United States—see Ciara Nugent, “They Left Guatemala for Opportunities in the United States. Now They Want to Help Others Stay,” TIME, April 13, 2022, https://time.com/6166459/guatemala-migration-economy-remittances/.

[10] Gallery Exhibition Texts.

[11] Extended Exhibition Texts.