Port de Banana

Lio-Bravo Bumbakini: Port de Banana

Littleton Museum

6028 S. Gallup Street, Littleton, CO 80120

May 30–August 10, 2025

Admission: Free

Review by Raymundo Muñoz

The quiet, pretty, super white suburb of Littleton, Colorado is not the first place you might expect to see an art exhibition inspired by the complicated and heartbreaking history of the Democratic Republic of Congo, since 1482, but people can surprise you. On display at the Littleton Museum, Port de Banana is a solo exhibition by Lio-Bravo Bumbakini—a Boulder/Brooklyn-based artist with Congolese blood and a Belgian upbringing—that weaves together a complex, visually and emotionally powerful, yet disjointed narrative about his deep cultural heritage. The earnest artist really reaches for the stars in this exhibition, pulling from historical events, folkloric mythologies, archetypes, and symbols, all expressed in his bold and energetic visual style.

An installation view of Lio-Bravo Bumbakini’s exhibition Port de Banana at Littleton Museum. Image by Raymundo Muñoz.

Port de Banana, by the way, is a small seaport on the coast of DR Congo, at the mouth of the mighty Congo River, and serves as a referential landmark from which the exhibition contextually disembarks. While the country is one of the largest in Africa and vastly rich in natural resources, it has endured a long and tortured history of colonization by European powers and civil wars, inflicting death, violence, slavery, poverty, disease, famine, corruption, and cultural upheaval on its people with untold millions of casualties. Bumbakini draws deeply from this pitch-dark well, creating works that metaphorically reflect the intense pain and sadness felt by the Congolese people then and certainly now.

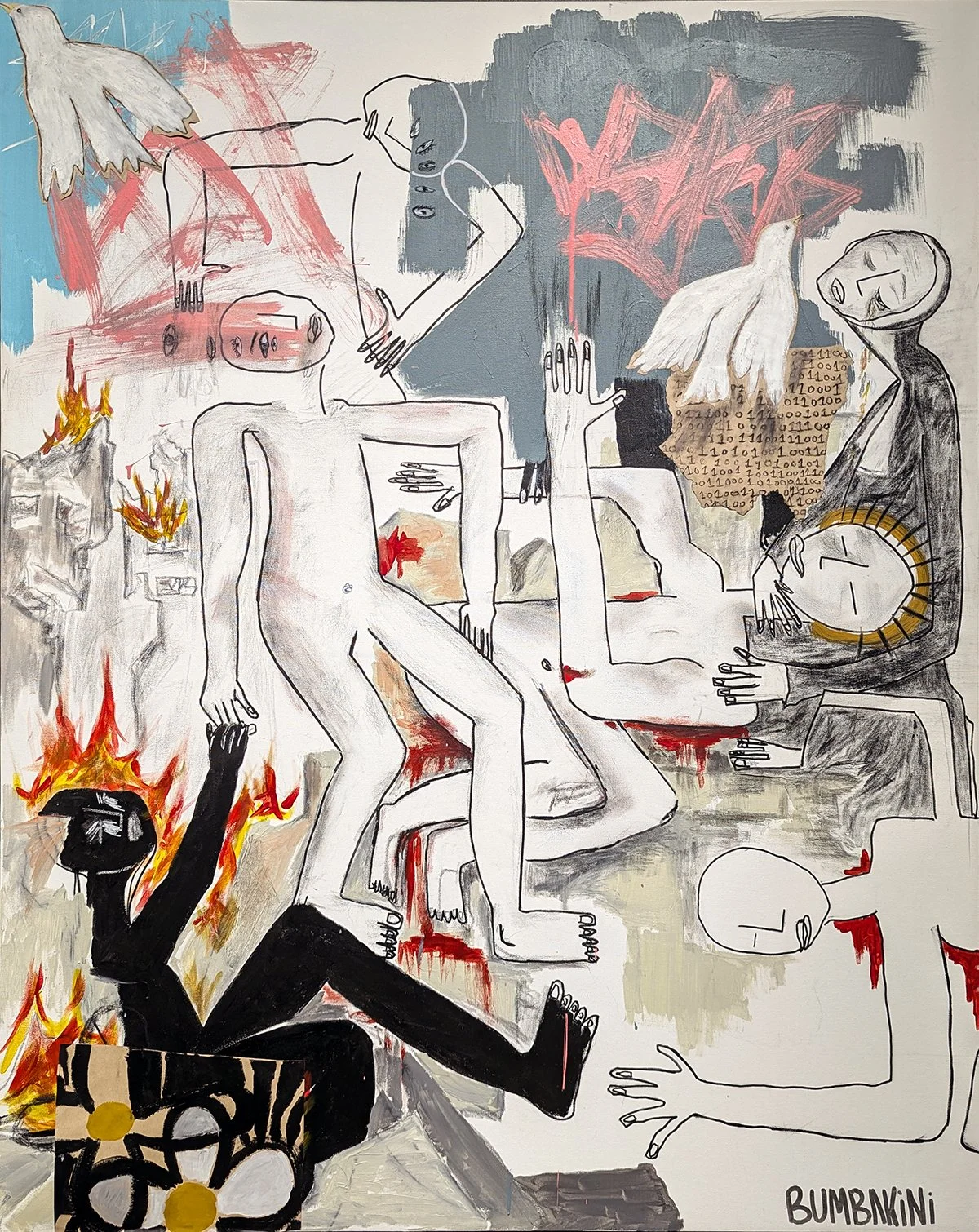

Lio-Bravo Bumbakini. As the World Turns…, 2023, house paint, acrylic paint, charcoal, and collage on canvas. Image by Raymundo Muñoz.

Consider As the World Turns…, a mixed media painting depicting a tangle of human forms in grief and agony. Blood pouring from wounds, fires burning on structures and people, the threat of choking from above, and a grieving nun holding a dying man amounts to an anxious and distressing piece on the themes of war and violence.

Lio-Bravo Bumbakini. Le Zaire (At the Mouth of the River), 2025, acrylic paint, watercolor, graphite, colored pencils, chalk, and charcoal on canvas. Image by Raymundo Muñoz.

Or take Le Zaire (At the Mouth of the River), by far one of the exhibition’s strongest works, with its bold, largely abstract and collage-like composition, which seems to compress a procession of scenes (perhaps representing centuries even) anchored by the central characters. One figure is dark, missing an arm and likely represents the Congolese people, and the other with a pink face and red headdress, perhaps a member of the clergy or ruling class. Blood red accents surround the dark figure, while magenta accents the other.

Barbed wire shapes coil across the top and a white dove flies up and away towards the blue sky, suggesting imprisonment and the desire for freedom. (The epic work’s title, by the way, refers to the Congo River’s previous name, the Zaire—a Portuguese corruption of the Kikongo word for “river.”) It’s a confident tumult of shapes and colors with blue flowing sections that suggest the grand river, carrying the power struggles in Congolese history along with its heavy currents.

Lio-Bravo Bumbakini. Batu Oyo (The People Here), 2025, linoleum relief ink handprint on cardstock. Image by Raymundo Muñoz.

Even arguably lesser works, like Batu Oyo (The People Here), a collection of rough-hewn linocut prints, suggest a sad story through depictions of a man and woman, a beach, boats, a cross, and a skull and cross bones.

Lio-Bravo Bumbakini. Afonso I (Youth) - Mwana Mboka (The Native Son), 2025, acrylic paint, charcoal, and aerosol on canvas. Image by Raymundo Muñoz.

Bumbakini references religion as well in Port de Banana; its view is ambiguous, though, and subtly subversive. Afonso I (Youth) - Mwana Mboka (The Native Son) refers to, in the artist’s words, “the first full-term Christian leader of the Kongo Kingdom.” He sits in a beach-like setting with a juju doll—likely a European import—on his lap, in a childlike display that suggests a cultural shift soon to occur.

Lio-Bravo Bumbakini. Le Batisimo de João I (Mwene Kongo Nzinga a Nkuwu - Lord of the Congo), 2024, acrylic paint, charcoal, house paint, and oil pastels on canvas. Image by Raymundo Muñoz.

His father João I was responsible for making Christianity the country’s official religion (influenced by Portuguese settlers in the late 1400’s), and the artist depicts him in Le Batisimo de João I (Mwene Kongo Nzinga a Nkuwu - Lord of the Congo). In this painting, the leader seems to be represented as a black bird with its head down, accepting a rosary necklace from a priest as a portrayal of Christian baptism, or conversion to Christianity.

Lio-Bravo Bumbakini. João I Great Rift, 2023, acrylic paint, charcoal, house paint, and paper collage on canvas. Image by Raymundo Muñoz.

In addition, the nearby painting João I Great Rift depicts the Kongo ruler carrying a dead white swan through a vibrant bunch of crimson red flowers, perhaps a swan song of sorts that delineates the Kongo kingdom’s previous traditions from the colonizer’s influence.

An installation view of Lio-Bravo Bumbakini’s exhibition Port de Banana at Littleton Museum. Image by Raymundo Muñoz.

While the artist acknowledges the miseries of the DR Congo, he also defies the darkness. Through a bright color palette and symbols of joy, hope, and strength (like birds, flowers, and leopards), Bumbakini champions a beautiful and peaceful spirit, ever reaching for the blue sky.

Lio-Bravo Bumbakini, The Passenger Series I-III, 2018, archival giclée prints. Photographs taken by the artist and his partner in Banana, DRC. Image by Raymundo Muñoz.

That special color palette seems connected to The Passenger Series I–III, a set of photographs taken by the artist and his partner in Banana in 2018. The digitally-processed giclée prints show contemporary daily life in the seaport town with images of the sea, houses on a hillside, palm trees, brightly colored store fronts, and women carrying thatched baskets and mats on their heads.

Lio-Bravo Bumbakini, photo from The Passenger Series I-III, 2018, archival giclée print. Photograph taken by the artist and his partner in Banana, DRC. Image courtesy of Littleton Museum.

The photos bring a contemporary and seemingly peaceful perspective to this largely historically-based exhibition, connecting the past with the present in a way that also sets the color tone for most of the exhibition. This includes dusky greens, shocking magenta, sky blue, warm yellows, and the soft pink of red soil, and they appear again and again throughout the artist’s works.

Lio-Bravo Bumbakini. Tosambela (A Boat and a Prayer), 2025, wool tufted on monk’s cloth. Image by Raymundo Muñoz.

Consider the abstract, tufted wool works Tosambela (A Boat and a Prayer) and Ko Salela Fet (Let’s Celebrate). (Why exactly the painter decided to make textile pieces is a mystery to me, but Bumbakini apparently relishes trying out different media (to varying degrees of success), so good on him). It’s hard to discern the visual references that inspired the titles, but the fiber works function nevertheless as beautiful compositions of color and form.

Lio-Bravo Bumbakini. Ko Salela Fet (Let’s Celebrate), 2025, wool tufted on monk’s cloth. Image by Raymundo Muñoz.

It’s worth noting, too: the artist isn’t necessarily the best draftsman, but he’s got a special understanding/intuition when it comes to abstraction. The way he cuts up his compositions through straight, swooping, and curvilinear lines, along with his beautiful color combinations and chunky brush work, makes it so that, in my mind, it doesn’t really matter what his point of reference is. His understanding of space, movement, and hue is truly special.

Lio-Bravo Bumbakini. Batu Mingi (Many Many Came), 2025, acrylic paint, watercolor, graphite, colored pencils, chalk, and charcoal on canvas. Image by Raymundo Muñoz.

The other epic work in the exhibition, titled Batu Mingi (Many Many Came), has such a propulsive energy with its frantic jumble and tumble (no fumbles on this one!) of abstract forms and faces. Visually framed by hard lines, vertical and horizontal cuts in composition, and the river-like baseline below, the work is softened by the inclusion of pink leopard spots and a subtle, rain-like cloud of lavender and sky blue swishy brush marks another absolute banger.

Lio-Bravo Bumbakini, Kiss the Moon, Dance Under Stars, 2024, acrylic paint, charcoal, house paint, and oil pastels on canvas. Image by Raymundo Muñoz.

Perhaps the piece that emotionally captures the entire exhibition’s themes the best is Kiss the Moon, Dance Under Stars. The painting portrays a feathery winged dancer with a skullhead, tip-toeing in ballet shoes among painterly clouds, hands raised to the heavens, eyes to the warm moon. It’s a messy and intensely layered painting that’s deeply evocative—a confrontation of death with joy and explosive feelings of freedom, created in a child-like style complete with rainbows flowing like scribbled crayon.

Lio-Bravo Bumbakini. If Life Should Be So Simple, 2023, acrylic paint on canvas. Image by Raymundo Muñoz.

Lio-Bravo Bumbakini, Linga Ngai, Linga Ngai Te (Love Me, Love Me Not), 2024, colored pencil, charcoal, chalk, and graphite on tan-toned paper. Image by Raymundo Muñoz.

The show falls a bit flat with the flowers pieces, unfortunately. Though Bumbakini’s flowers represent everything from life and death (see: If Life Should Be So Simple) to love and memory (see: Linga Ngai, Linga Ngai Te (Love Me, Love Me Not)), their overly comical forms tend to work against the exhibition’s heavy themes.

An installation view of Lio-Bravo Bumbakini’s exhibition Port de Banana at Littleton Museum. Image by Raymundo Muñoz.

Seesawing between abstraction, expressionism, and surrealism through various media, Port de Banana may have benefited from focusing the theme and artistic styles, but undoubtedly, this is the best I’ve seen of the artist’s work and presentation. Bumbakini actually gets close to the stars he’s reaching for in this show. Kissing the moon instead perhaps, but, by my humble measure, that’s still pretty damn far.

Raymundo Muñoz (he/him) is a Denver-based printmaker and photographer. He is the director/co-curator of Alto Gallery and board president of 501(c)(3) non-profit Birdseed Collective. Ray is guided by the principle that art is a bridge, and it connects us to ourselves and each other across time and space.