Evocation

Evocation

Walker Fine Art

300 W. 11th Avenue, Unit A (enter on Cherokee Street), Denver, CO 80204

July 14-September 2, 2023

Admission: Free

Review by Raymundo Muñoz

On a long road trip through the countryside, what you see and experience depends a lot on which window you’re sitting by. Changing forms and colors call forth in our minds and hearts anything from personal truths to great mysteries. In a similar way, Evocation―the current exhibition on view at Walker Fine Art―presents selected works from six artists that invite introspection through the common themes of nature, landscape, and memory.

A view of the exhibition Evocation at Walker Fine Art. Image courtesy of the gallery.

It’s a well-curated show with a strong backbone of fine, representational painting from Matt Christie, Doug Haeussner, Peter Illig, and Virginia Steck, further enhanced by striking abstract work from Atticus Adams and Kim Ferrer. Organized by artist, each body of work in Evocation is rich in concept and execution and worth considering alone. Viewing them collectively, though, implies a larger narrative―one encompassing both inner and outer nature, human and otherwise.

Works by Kim Ferrer in the exhibition Evocation. Clockwise from bottom: Surrender, ponderosa pine, steel, and porcelain, 24 x 50 x 16 inches; Cycles of Change (take it as it comes), graphite prints on Kozo paper and porcelain, 82 x 190 x 2 inches; Shed, butternut, porcelain, swiss rug rope, and steel, 85.5 x 6 x 11.5 inches. Image by Raymundo Muñoz.

Perhaps laying the conceptual foundation for the show, the front gallery is devoted to the exquisite and meditative abstract works of Kim Ferrer. Composed of wood, porcelain, paper, and fiber, Ferrer’s repeated use of natural wood patterns suggests the influence of nature’s passing seasons. Tall sheets of Kozo paper hand-rubbed with sparkling graphite hang like ghostly trees in Cycles of Change (take it as it comes). Patterned with squiggly bark beetle tracks, the series has the look of printed etchings―dark, atmospheric, yet punctuated by hard-edged lines. Floating alongside fragile porcelain casts of the same beetle-ridden trees, these works are a powerful statement on the cycle of life and death.

Kim Ferrer, Regeneration, aspen, graphite, and steel, 79 x 41 x 8.5 inches. Image by DARIA.

A detail view of Kim Ferrer, Regeneration, aspen, graphite, and steel, 79 x 41 x 8.5 inches. Image by Raymundo Muñoz.

Across the room, Regeneration visually parallels yet contrasts with the paper series using actual beetle-scrawled aspen that is cleanly hewn, graphite-covered, and hung from a metal rod, suggesting the unmistakable inclusion of human influence. In between these works is a collection of wall-mounted and free-standing pieces that mix raw and finished elements to great effect. In all, Ferrer’s work is a cohesive and respectful balance of natural and human-crafted design, offering powerful meditations on impermanence.

A view of Matt Christie’s paintings in Evocation at Walker Fine Art. Image by Raymundo Muñoz.

The life-death cycle comes across also in the solemn and evocative landscape oil paintings of Matt Christie. Elevated beyond mere depictions of natural scenery, the landscapes here attain a much deeper, more personal and metaphorical purpose. According to the artist’s statement, nature has always had a profound effect on him and he uses landscapes to “explore [his] own psychological nature” and “[connect] inner nature with outer nature.” Christie’s compositional elements are often subtle, yet deliberate, making deft use of color and visual signs of life and decay.

Matt Christie, Unknown Interior, oil on panel, 60 x 48 inches. Image by DARIA.

Consider Unknown Interior, composed of bloomed brush in a dry field against a mountain sunset background. Held up by green stems, the small golden flower bunches have an attractive relationship with the saturated warmth of the setting sun. Central to the composition as well is a shadowy, empty space marked by cool purples and drooping stems. The implication of standing at life’s edge is apparent.

Matt Christie, Magician, oil on panel, 60 x 48 inches. Image courtesy of the gallery.

Christie pushes this relationship further in Magician―a haunting piece that seems to zoom in on the same dark scene, presenting an occupant of sorts: a blackbird. With a slick blue sheen and a piercing eye, the bird perches ominously among the blue-purple stems that seem to radiate from it. Head turned from its doings, the bird stares at you in a menacing and chilling way.

Matt Christie, Standing Solitary, Love Falls from the Sky, oil on panel, 60 x 48 inches. Image by DARIA.

Still, the remnants of life persist, offering respite and hope among the grave overtones. Consider Standing Solitary, Love Falls From the Sky, a dark and lonely piece depicting a spare, leafless tree in a field being showered from above with bright, red roses. Or yellow flowers in a frozen, snow-laden field, warm and glowing at the horizon in Untitled. These self-described “self portraits” suggest much about the introspective nature of the artist, holding onto beauty even through hard and inevitable life changes.

Virginia Steck, Forest Reign, oil on canvas, 60 x 48 inches. Image by DARIA.

On the other end of life’s spectrum, we find the lively and lovely oil landscapes of Virginia Steck. Where Christie’s work often takes a step back to show a broader perspective, Steck’s compositions pull the viewer into settings that are intimate and enveloping. Works like Forest Reign and Wildgrassland are inspired by the artist’s frequent wandering hikes, “searching for small moments of wonder.” Steck paints such moments in an abstract impressionist style, lending her compositions a dizzying sense of movement.

Virginia Steck, Sundrenched, oil on canvas, 48 x 60 inches. Image by DARIA.

Take Sundrenched, a piece filled from top to bottom with flourishing forms. Frankly, it’s almost too much to take in at once with its frenzy of flowers. Get closer though, and those layers of energetic and dashing brushwork become palpable, akin to a tickling niacin rush. This play with chaos seems key to the artist’s aim to channel “the wild and creative energy of the natural world.” [1] Still, quieter pieces like The Leaping Sun reveal Steck’s sensitive consideration of light that is arresting and hypnotic in a way reminiscent of water.

Atticus Adams, Combahee V, aluminum, mesh, gesso, acrylic, and wire, 37 x 30 inches. Image by DARIA.

Adjacent to Steck and occupying the rear gallery wall are the eye-catching abstract wall sculptures of Atticus Adams. Described as “biomorphic [...] neo-Appalachian folk art,” the works are composed of painted aluminum mesh that’s crimped, bent, and pinched into large, elegant forms. [2] Inspired by fond childhood memories looking through screen doors, there is indeed a playfulness to the three pieces on display. The combination of curling shapes, patterns, and highly contrasted elements in Combahee V, for instance, suggests collections of microscopic creatures, writhing, undulating, and blooming in a liquid environment. Within the show’s nature-inspired context, repeated forms like those in Sujoon Pierrot and Sujoon Carnival Night recall the wriggling beetle tracks in Ferrer’s works.

Atticus Adams, Sujoon Carnival Night, aluminum mesh, gesso, acrylic, and wire, 52 x 52 inches. Image by DARIA.

There’s an inherent mystery to Adams’s abstract work, and mystery plays a key role as well in Doug Haeussner’s figurative oil paintings. Based on found vintage Polaroids procured on Ebay years ago, the candid narratives―part of his Snapshots series―are as much mysteries to the self-described nostalgia fan as to the viewer.

Doug Haeussner, Beach House, oil on panel, 30 x 30 inches. Image by DARIA.

The scenes presented are pleasant and idyllic (e.g. a man toasting his drink in a pool in Paradise, a smiling woman in a red bathing suit in Caribe), further aided by a creamy aesthetic reminiscent of encaustic (see: the striped shadows in Beach House).

Doug Haeussner, Paradise, oil on panel, 30 x 30 inches. Image by DARIA.

Additionally, Haeussner paints a magical, bokeh-like (out of focus) effect in the backgrounds of Third Date and Paradise that lends the series a beautiful, dreamlike quality. While the real context of the artist’s subject matter may be lost to time, a record of some sort remains, inspiring a range of collective interpretations and maybe even fond daydreaming from artist and viewer alike.

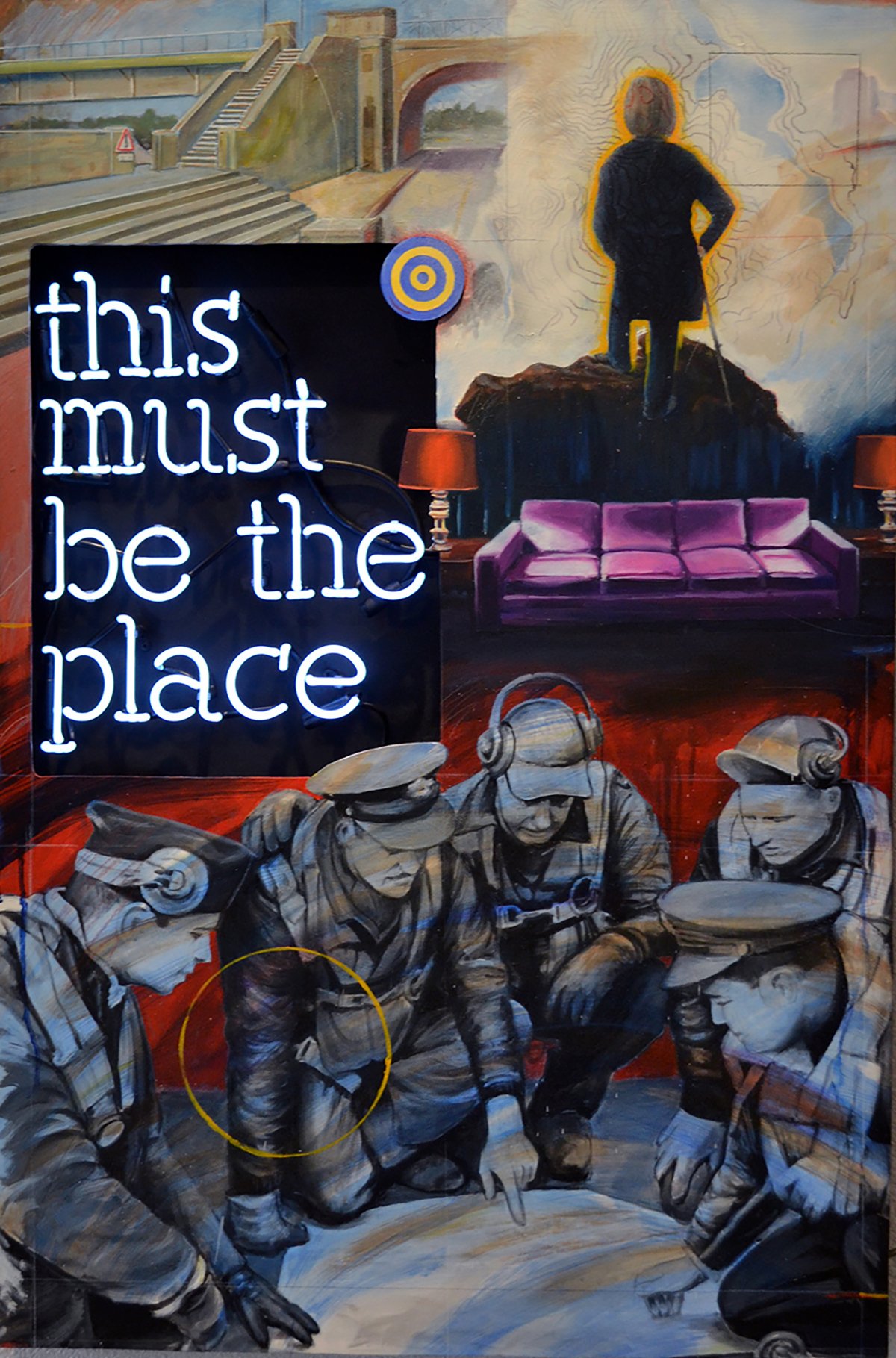

Rounding out the show, Peter Illig’s bold and surreal oil paintings are dreams in their own right. Packed with symbolic imagery accented by neon text, the landscapes Illig journeys through, much like Christie, are mental and emotional. While Christie’s pieces read like literal landscapes, however, Illig’s works are something entirely different. His representation of the subconscious is based on dynamic montages that seem to access different narratives all at once.

Peter Illig, This Must Be the Place, oil and enamel on canvas with electric neon sign, 40 x 26 inches. Image by DARIA.

Inspired by the interconnectedness of things, Illig likens these associations to “a kind of time travel.” [3] In This Must Be the Place, for instance, a group of WWII-era airmen―painted in sepia tones like an old photograph―gather around a map, surrounded by a curious collection: a blue and yellow target, an empty purple couch, a staircase connecting paths, and a person at the edge of an overlook. While the narratives it suggests differ, the common theme of searching for a destination seems evident.

Peter Illig, It Was All A Dream, oil and enamel on canvas with electric neon sign, 37 x 24 inches. Image by DARIA.

Much like Haeussner, Illig is a lover of nostalgia, albeit expressed in his own way by employing elements like old photo and movie references, comic book imagery, and neon signs. In It Was All A Dream, a house floats through space and, along with the title, almost certainly references Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz.

Peter Illig, We See What We Want, oil and enamel on canvas with electric neon sign, 37 x 24 inches. Image by DARIA.

Illig’s already complex compositions are pushed further with allusions to design and art-making. Consider We See What We Want, in which the drawn guidelines he uses for organizing his compositions aren’t covered over, but retained. Studies of a portrait bust in the top corner contrast with a simple block drawing along with one more fully rendered. It’s a clever piece, especially considering the main imagery of a happy couple on a motorcycle. The female driver is blindfolded, the male passenger is holding her waist, and neither person is steering, oblivious to the obstacles ahead. As such, the work seems to comment on the way we simplify and break down what we see (i.e. reality) into what we can understand or want to deal with.

A view of the exhibition Evocation at Walker Fine Art. Image by DARIA.

The nature of our shared reality, traveling through space and time, is indeed strange and filled with mystery. Evocation touches on this beautiful enigma with the artworks of six humans, calling forth whatever comes, inviting us to see what we want as we gaze at forever.

Raymundo Muñoz is a Denver-based printmaker and photographer. He is a current artist-in-residence at RedLine Contemporary Art Center and director/co-curator of Alto Gallery. Ray is guided by the principle that art is a bridge, and it connects us to ourselves and each other across time and space.

[1] From Virginia Steck’s artist statement.

[2] From Atticus Adams’ artist statement.

[3] From Peter Illig’s artist statement.