En La Memoria

Román Anaya and Louis Trujillo: En La Memoria

O’Sullivan Art Gallery, Regis University

3333 Regis Boulevard, Denver, CO 80221

January 20–March 27, 2026

Admission: free

Review by Kamden Hilliard

Through March 27th, the O'Sullivan Gallery at Denver's Regis University is hosting Román Anaya and Louis Trujillo's En La Memoria—a series of self-portraits, sculpture, and paper flowers that confound traditional ideas of gender, illness, and the religious. This unapologetically queer and reverent exhibition interrogates gender performance, illness, and religion through a variety of forms to articulate a queer hope.

An installation view of Román Anaya and Louis Trujillo’s exhibition En La Memoria at Regis University’s O’Sullivan Art Gallery. Image by Kamden Hilliard.

Anaya and Trujillo's self-portraits directly confront common logics of gender and masculinity. Anaya has defined "machismo" as, among other things, "the right to dominate," but his feminine deployment of gender puts a sly twist on this logic." [1] Whereas domination is about force or brute rule, in photographs like Mari, Con Amor 2.24.2019, it becomes a question of attention and self-affirming power. Rather than domination over others, Anaya dominates by taking ownership of his self-image in a playful, provocative, and powerful self-portrait.

Román Anaya, Mari, Con Amor 2.24.2019, 2019, digital C-print, 35 × 24 inches. Image by Kamden Hilliard.

Mari, Con Amor, the title of the series, translates to "Faggot, With Love," transforming the epithet into a site of identification, one where the artist not only sees himself lovingly but also challenges the viewer to see him, as well. Rather than butching up (becoming more stereotypically masculine), Anaya embodies the queerness, drama, and beauty at the heart of this word, rewriting gender's persistent grammar into something capable of holding him.

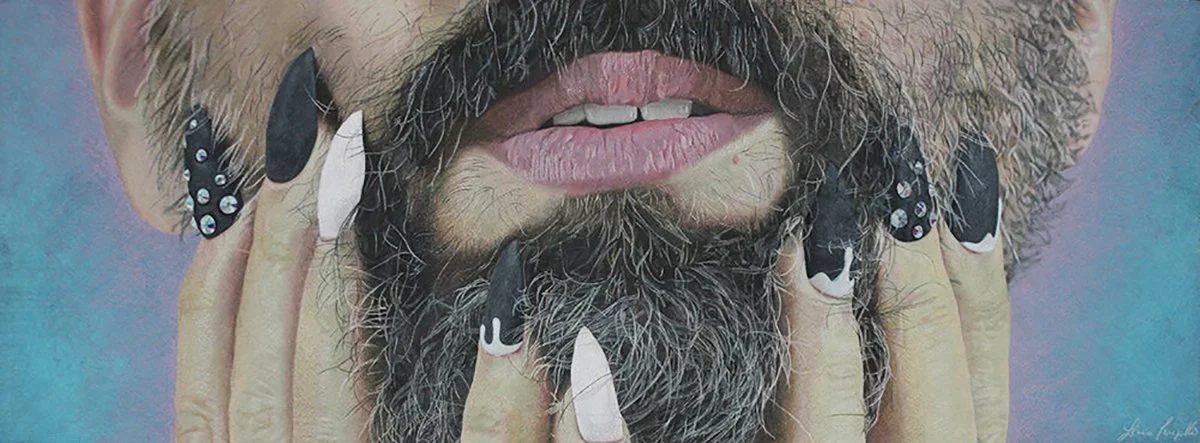

A detail view of Román Anaya’s Mari, Con Amor 2.24.2019, 2019, digital C-print, 35 × 24 inches. Image by Kamden Hilliard.

There is also a technical flair that continues to drive this conversation about gender. Anaya's classical, pin-up-like posture draws the eye up his bent leg, where a band of light on the pantyhose guides the eye to his fulsome backside, here merely implied but in other images, like Untitled, Anaya centers his subjects' flesh.

Román Anaya, Mari, Untitled, 2018/2019, digital C-print, 24 × 32 inches. Image by Kamden Hilliard.

A detail view of Román Anaya’s Mari, Untitled, 2018/2019, digital C-print, 24 × 32 inches. Image by Kamden Hilliard.

In the religious tradition, nudity is not necessarily lewd, but becomes a way to witness, honor, and beautify God's creations on earth. Similarly, Anaya's queer subjects complicate traditional notions of masculinity. The ISMO series, from which this Untitled image comes, complicates notions of gender beyond the historical and normative. The stylized tears streaming down the subject's face and the light emanating from behind his head cast him as a devotional figure, asserting queerness as a site of holiness or worship.

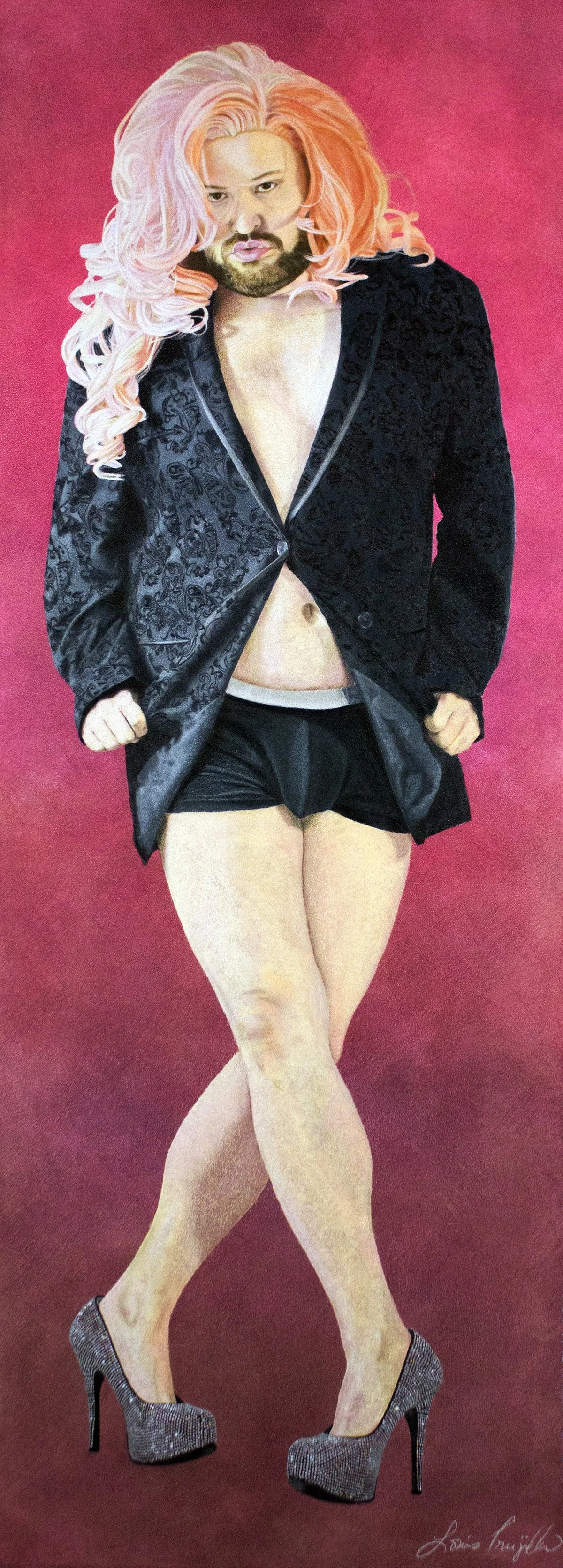

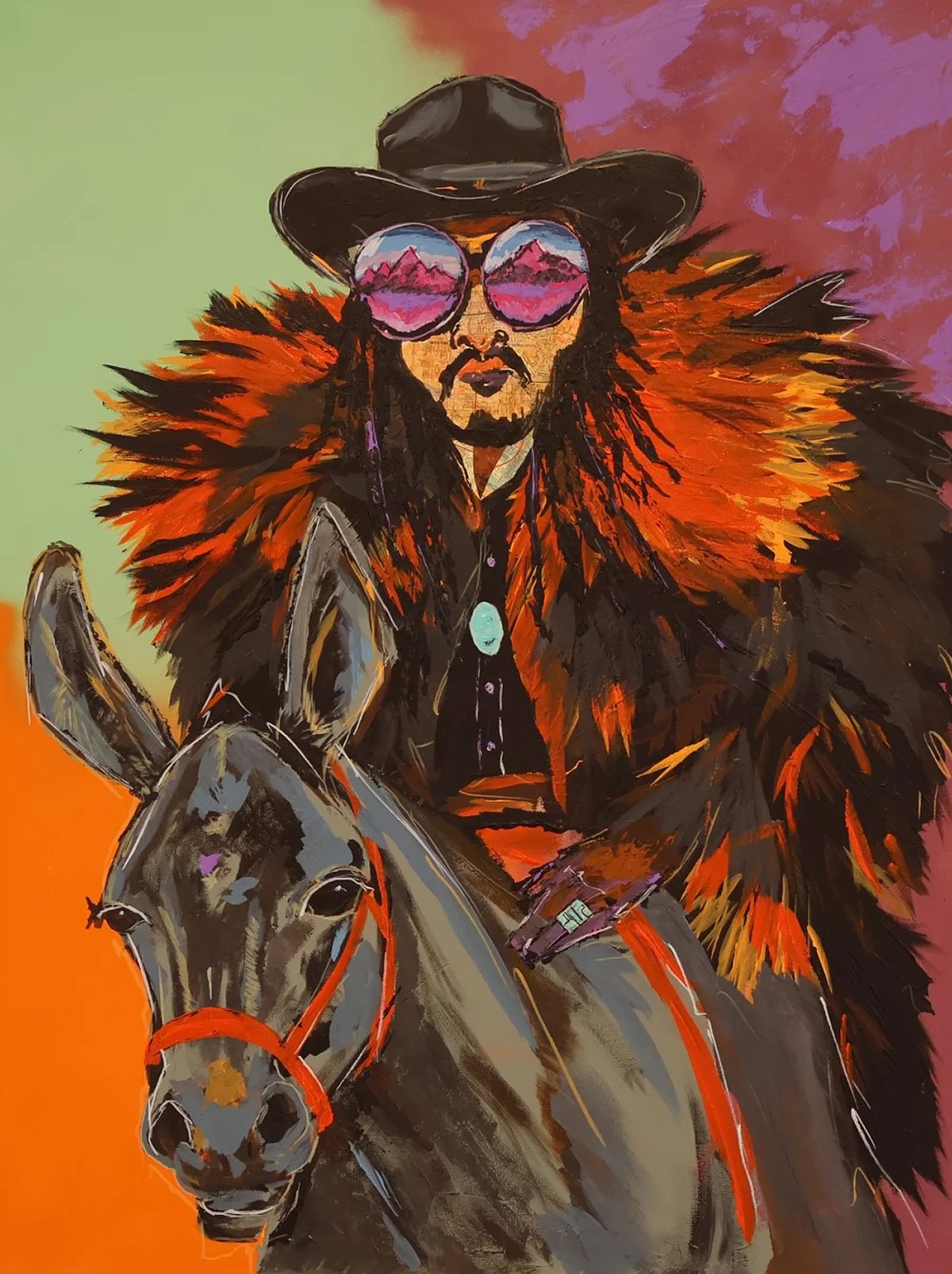

Louis Trujillo, Fat, Femme, and Fierce, 2019, colored pencil on paper, 41.5 x 15 inches, from the Sissy Series. Image courtesy of the O' Sullivan Art Gallery.

While queerness is typically rendered as a failure of the masculine, here Anaya offers queerness as an ideal form of the masculine. Trujillo's Fat, Femme, and Fierce provides a similar embodiment of queerness as a perfect form. What was a site of othering and shame became a site of power and beauty. In this self-portrait, Trujillo captures himself in bombastic drag, complete with stunning stilettos and a peach-blonde wig.

Trujillo stares down the camera in a feminine power stance: legs crossed, hands clenched around the lower lapel of his black jacket, a full beard, short shorts, and fantastic shoes. Like the title, Trujillo demands to be seen as his fabulous, glorious self.

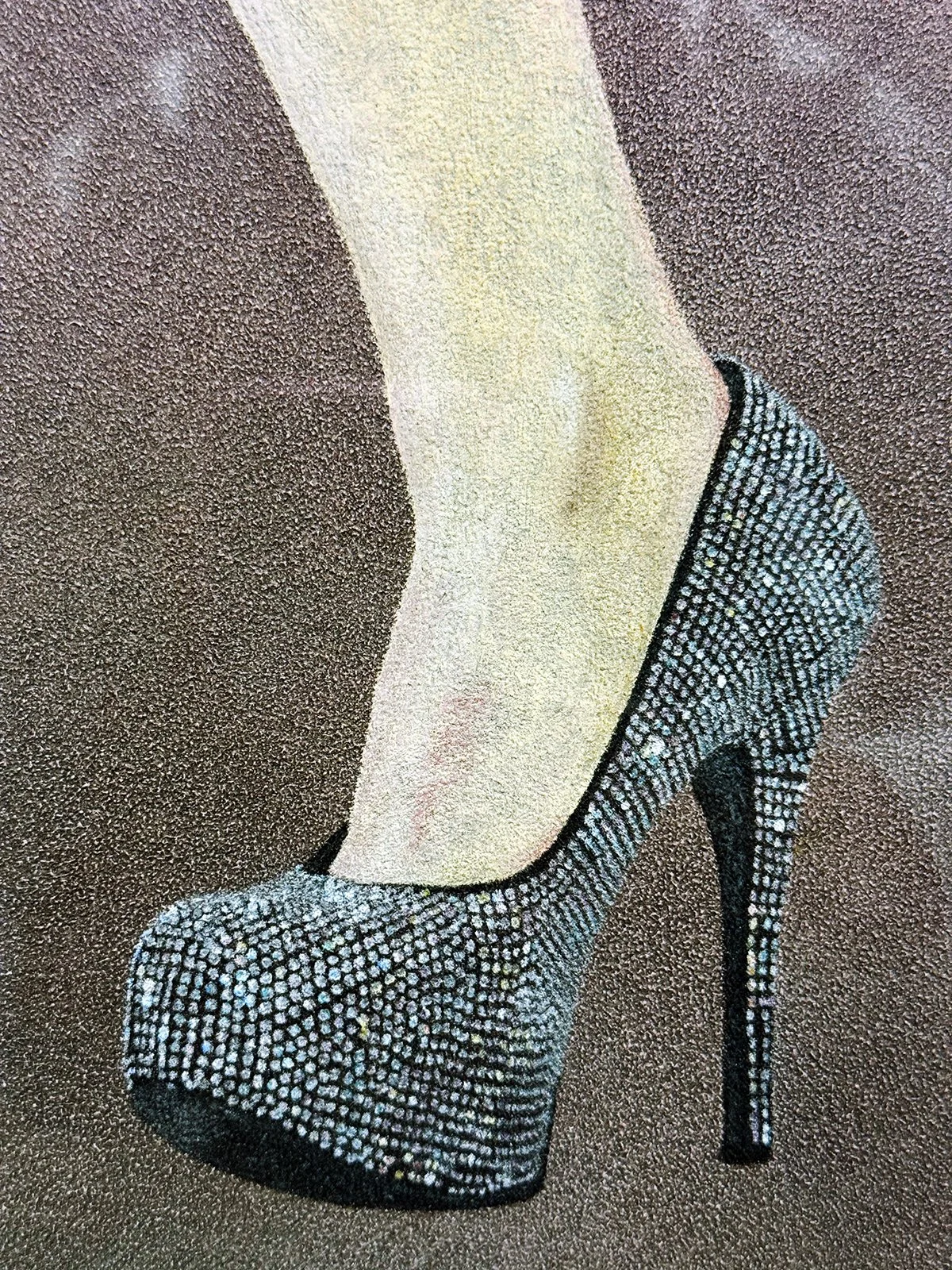

A detail view of Louis Trujillo's Fat, Femme, and Fierce, 2019, colored pencil on paper, 41.5 x 15 inches, from the Sissy Series. Image by Kamden Hilliard.

The artist does not understand the feminine as thin, Anglo-Saxon, or petite, but as a substance to which we all possess access, and he thrives in his access. Like live drag performance (another one of Trujillo's forms), the drawing is at once playful, philosophical, and sexy. In a contemporary moment dominated by anti-queer sentiment and legislation, Trujillo demands to be seen for what he is: a "fat, femme, and fierce" person who shall be regarded as such; similarly, Trujillo and Anaya complicate the viewer's experience of illness.

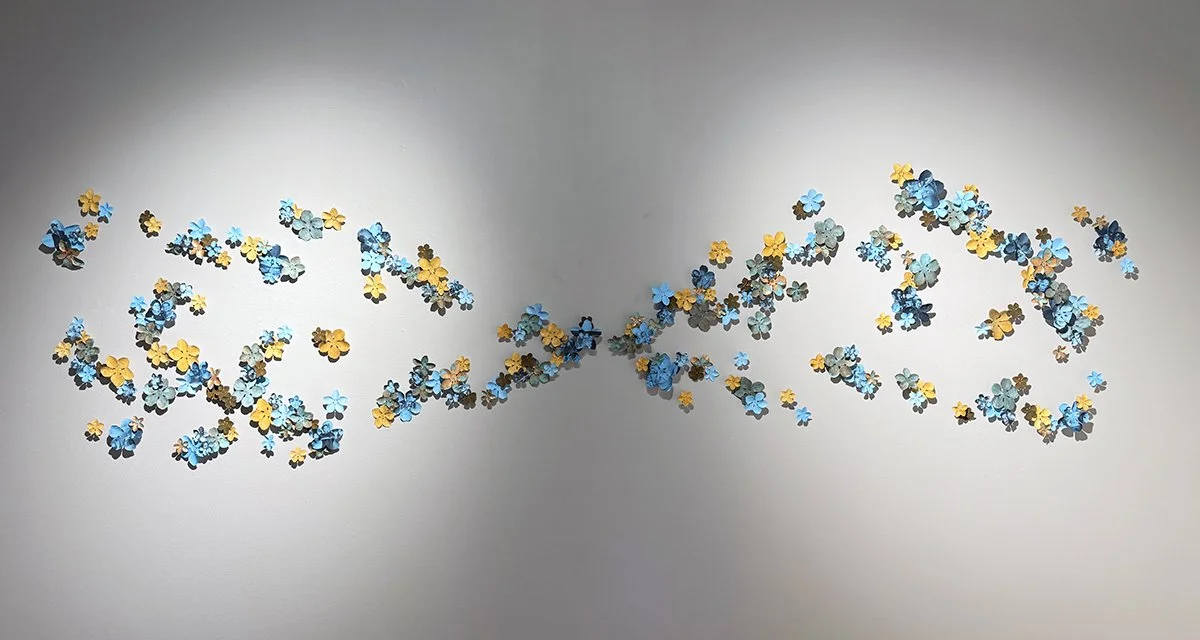

Louis Trujillo, So I Won't Forget, 2018, gouache, acrylic, rust, patina, copper leaf, digital C-prints on paper, and pins, dimensions variable, from the Forget Me Not series, 38 × 137 × 1 inches. Image by Kamden Hilliard.

Questions of illness—what it means to be sick or well, how we see and care for each other in conditions of unwellness, and what recovery means for each of us—find fertile ground in Trujillo's Forget Me Not series. Trujillo's series depicts "the loss of the mind through mixed media works on paper." [2] In honor of family and human histories of Alzheimer’s, he crafts paper flowers, often from family photos, paints them with a variety of media, and artfully arranges them in shapes like a cloud of butterflies or an infinity sign that resembles a bosom.

A detail view of Louis Trujillo's So I won't forget, 2018, gouache, acrylic, rust, patina, copper leaf, digital C-prints on paper, and pins, dimensions variable, from the Forget Me Not series, 38 × 137 × 1 inches. Image by Kamden Hilliard.

The numerous flowers remind one of the folding of a thousand paper cranes in the Japanese tradition, which symbolizes recovery, long life, and luck. Trujillo's innumerable flowers offer a similar set of feelings while paying tribute to the challenges of Alzheimer's.

Trujillo paints the individual flowers in acrylic, copper leaf, gouache, patina, and rust to offer a sense of individuality—the unique features of each memory—and uniformity—the similarities possessed by all memories. This flower-making technique also appears in his Sissy series, where a beautiful smattering of butterflies swirls around a set of drawings.

An installation view of works by Louis Trujillo in the exhibition En La Memoria at Regis University’s O’Sullivan Art Gallery. Image by Kamden Hilliard.

The spilling out and the sharing of these flowers is bountiful, productive, and vibrant, and it inextricably links queerness and memory. To be queer is to remember who you are and what you deserve in the face of a world that marks you as unnatural, “extra,” “too much,” or not enough. The intentional placement offers a sculptural element where Trujillo manipulates distance and density to produce a unique and memorable effect.

It is also lovely to see Trujillo "give her her flowers," so to speak, those flowers which often go ungifted in this life. The experience of illness and the sadness it evokes make space for the beauty Trujillo offers. Similarly, for a disease which is progressive, irreversible, and degenerative, the infinity of these flowers suggests that those we forget, those who are forgotten, and those who forget us are never gone…not really.

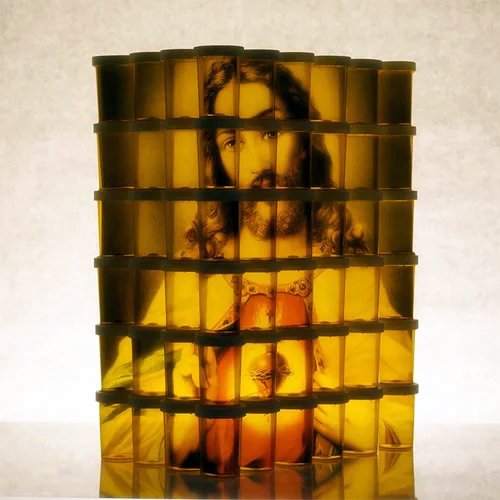

Román Anaya's Sagrado Corazón de Jesus (replica), 2015, transparency film and pill bottles, 15 x 15 x 9 inches. Image courtesy of Román Anaya's artist website.

VOID is a "series that helps [Anaya] address the hardships [he] experience[d] day to day as an epileptic and has helped [him] cope with the many medical hardships [his] family has experienced." [3]

His photographic mosaic in the show appropriates the Catholic devotional image "The Sacred Heart of Jesus." Anaya printed the image on transparency film, cut it into equal pieces, and placed each in a transparent pill bottle. When stacked, they form an estranged mosaic, playing with the scale and dimensions of the original image and casting the whole scene in an orange, pharmacological glow.

An alternative view of Román Anaya’s Sagrado Corazón de Jesus (replica), 2015, transparency film and pill bottles, 15 x 15 x 9 inches. Image by Kamden Hilliard.

The image suggests that one's experience of the world mediates sight, and that in the cases of bipolar disorder and epilepsy, which complicated Anaya's life, the medicalized experience can influence how one sees God. This influence is not entirely negative; from various distances and angles, the mosaic transforms each time, highlighting how alternative experiences can illuminate new angles, perspectives, and intentions that were present all along.

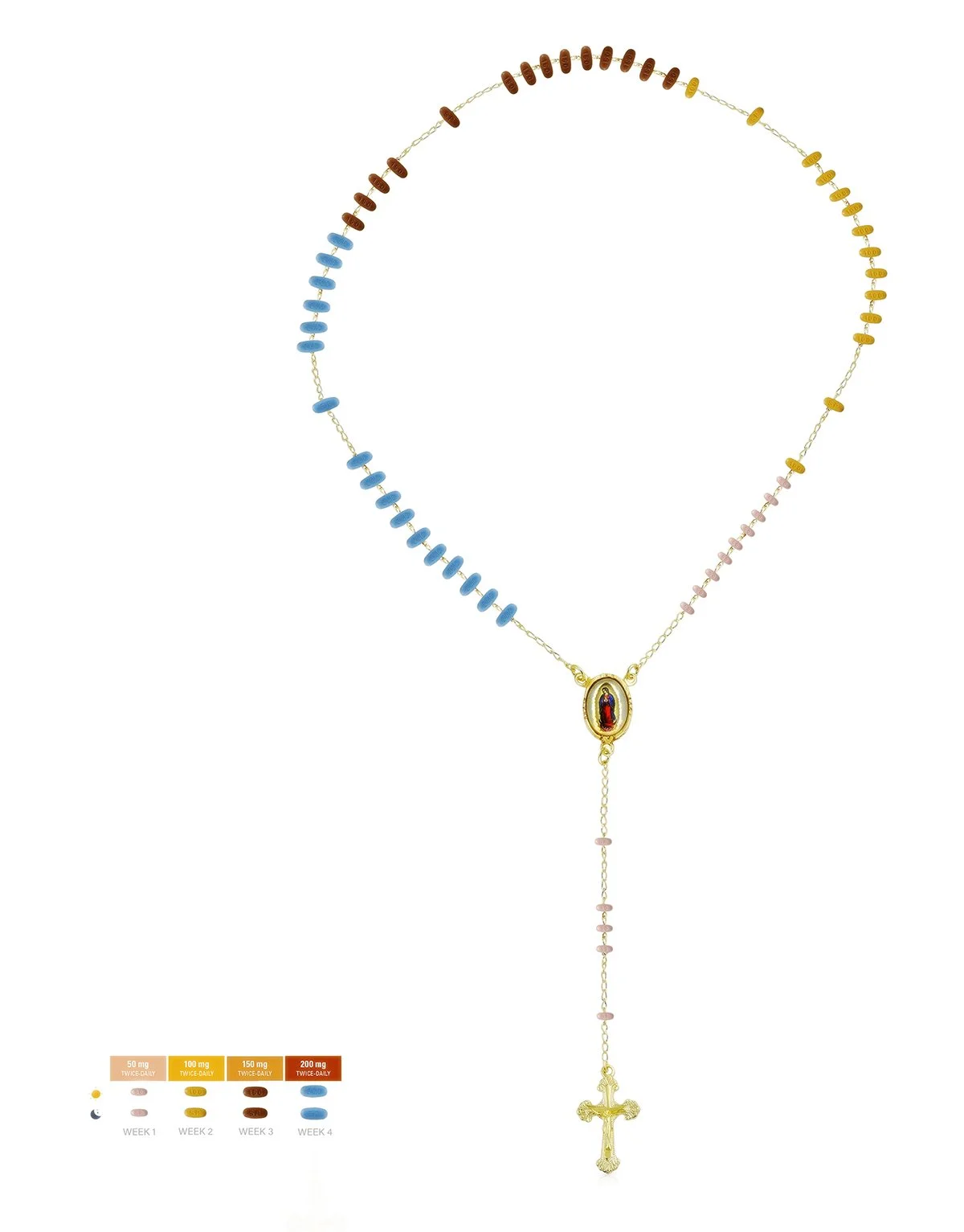

Anaya's thoughtful and inventive use of material culture extends across VOID, which transforms medical information sheets into devotional texts, lacosamide tablets into a rosary, and a driver's license that Anaya once used—before it was rendered VOID because of their epilepsy diagnosis—into meaningful visual art. Anaya's attention to and care for the material life of illness is a testament to how we understand and survive care. Art is a medication—a treatment for a world that dispenses violence and debility at random.

Román Anaya, 4-Week Lacosamide Taper, 2019, digital C-print, 31.25 × 24 inches. Image courtesy of O'Sullivan Art Gallery.

The VOID series addresses the literal and affective "voids" that illness forces into our lives, and how we might fill them through ritualized transformation. Pharmacy documentation becomes an expression of faith, and lascomide, too, finds new life as a rosary, suggesting that if we are all holy (we are), then how we come back to ourselves is holy too.

Anaya combines the objects of healing and worship in a dizzying blur of ritual and faith. A titration, the beginning of a new treatment, is an expression of faith like no other. To admit the foreign substance, even if effective and benign, is to put oneself at the mercy of a faceless medical corporation. Similarly, aside from the drama, love, and poetics at the heart of the Catholic religion, there lie histories of colonization, corruption, and abuse in locales near and far. As a survivor does, Anaya takes the good and leaves the bad in an object that literalizes the long ritual that is healing.

The works by Louis Trujillo and Román Anaya on display at Regis University are well worth seeing. A range of interests, techniques, and references intersect to offer a hopefulness for what it means to heal, to worship, and to be queer. At the risk of being obvious, the title of this exhibition translates to In Memory Of—a phrase of dedication, memorial, and even reverence for the dead. And in a moment when queer life, even in death, so often goes disrespected, to honor the memory of Román Anaya, who passed on April 28, 2021, is to return to the fact of his sacredness.

Louis Trujillo's thoughtful and balanced curation and participation make the entire endeavor an art object unto itself, for what is art's job if not to remind the viewer of the beauty of the world and its queerness? En La Memoria takes Spinoza seriously when he claims that "...all things are conditioned to exist and operate in a particular manner by the necessity of the divine nature." [4] This exhibition knows that all people, all things that exist––even gender performance, disability, and queerness––are holy, holy, holy.

Kamden Hilliard (they/them) is a trans poet, educator, and fish keeper based in Colorado. You can find them online at kamdenihilliard.com.

[1] From the artist’s website.

[2] Ibid.

[3] From an Instagram post by the artist: https://www.instagram.com/romananaya/.

[4] Baruch Spinoza, Ethics, Part 1, Proposition 29, https://www.gutenberg.org/files/3800/3800-h/3800-h.htm.