Annalee Schorr

Artist Profile: Annalee Schorr

Taking Her Time

by Parker Yamasaki

Annalee Schorr likes to be in control. She’ll be the first to tell you.

“How much do you know about Spark Gallery?” the eighty-five-year-old artist asks moments into our first meeting, taking the reins of the conversation. “That's where I am so involved, and we've got a lot of exciting stuff going on. So, I'd like to talk about that.”

An installation view of Annalee Schorr’s Pattern Play exhibition at Spark Gallery, 2016, with Plexiglas® paintings and duct tape patterned floor. Image by Marcia Ward/The Image Maker Denver.

Schorr became a member of the alternative artist co-op in 1985 after burning out on traditional commercial galleries.

“You work very hard,” she says about being a member-artist of Spark. “You don't just produce the art for shows, but you also plan the installations, you scrub the floors and paint the walls and cook the food for the openings. But you're in total control of it all, and you can show any crazy thing you want to show.”

Annalee Schorr, Navajo Blanket, 2022, acrylic on emergency blanket, 84 x 50 inches. Image by Marcia Ward/The Image Maker Denver.

Spark is now one of Denver’s longest-running artist co-ops, and over its forty-five-year history has occupied three different spaces. The gallery recently left its home of fifteen years on the corner of 9th and Santa Fe Drive to take over a place next to the Denver Art Museum.

Schorr has also been pushed around the city and just recently moved into a ground floor studio at Prism—a complex of artists’ studios in an industrial corner of Denver’s West Side.

A view of Annalee Schorr’s studio. Image by DARIA.

“This is my fifteenth studio since I started working full-time as an artist,” Schorr says. “You could almost plot how Denver has gentrified by the places I've been thrown out of.”

That constant churn doesn’t square with Schorr’s internal ethos of order, efficiency, and control—elements that show up repeatedly in her works.

Annalee Schorr, Cubism #2, 2016, acrylic on Plexiglas®, 24 x 30 inches. Image by Marcia Ward/The Image Maker Denver.

To put it in overly simple terms: Schorr likes cubes. She is, in fact, “obsessed” with them, she says. She likes straight lines and deadlines. She uses grids, patterns, and repetition. She takes inspiration from quilts, Navajo textiles and tiles, and is deeply motivated by Sol LeWitt.

And while she speaks effortlessly about what she likes and who inspires her, talking about her own work doesn’t come as naturally.

Annalee Schorr, Mexican Serape, 2022, 84 x 50 inches, acrylic on emergency blanket. Image by Marcia Ward/The Image Maker Denver.

“I'm sure it is about making the world more orderly, making the modern world more orderly,” she says, half-heartedly. “But I'm not a very verbal person,” she adds, opting out of explanation.

What she is comfortable talking about are the issues that drive her work.

Schorr has always been politically active. In the 1970s she was heavily involved in the early environmental movement. She lobbied the state legislature and campaigned for King Soopers to start a recycling program with a group called the Educated Consumers Organization, or ECO.

An installation view of Annalee Schorr’s Mirror Mirror on the Wall at Spark Gallery, 2023, mirrored mylar on walls, with Plexiglas® paintings and 3D sculptures. Image by Marcia Ward/The Image Maker Denver.

“It was all about things you can do in your daily life to become more environmentally sensitive,” she says. “Really ‘radical’ things like turning the water off while you’re brushing your teeth and using as few disposables as possible.”

She planned on going back to school to get a degree in environmental science, “so I'd know what I was talking about,” she says. Then she took an adult art class at the Opportunity School, a historic Denver institution that lifted the age limits on education. As she puts it, “that was it.”

A view of Annalee Schorr’s studio wall. Image by DARIA.

She never went fully back to school—for environmental science or for art—but instead dove headfirst into a self-taught artistic career. During the early days she’d “punch the time clock” by committing at least twenty hours per week to painting, she says. “I knew that if I was going to be serious about art, I needed to just start doing stuff.”

Shortly thereafter, she started landing gallery shows, beginning with Brena Gallery in Denver in 1978.

Annalee Schorr, X-it, 1985, acrylic on canvas, 48 × 48 inches. Image by DARIA.

In the mid-1980s, around the time Schorr found Spark, she started working with X’s—the letter and symbol—as a unit to signify what she calls “crossed out lives.” It was the beginning of the HIV/AIDS epidemic and people around her were dying by the thousands, including her brother-in-law. She painted 50,000 X’s across five square panels—the approximate number of deaths at that time.

A detail view of Annalee Schorr’s X-it, 1985, acrylic on canvas, 48 × 48 inches. Image by DARIA.

The canvases are not neat, orderly, or gridded like her other work. They are cluttered and layered, thick with the colorful X’s.

Annalee Schorr, 40,000 Crossed Out Lives: An X for Each U.S. Gunshot Death in One Year, 2020, mixed media on emergency blankets, diptych, each 82 x 54 inches. Image by Marcia Ward/The Image Maker Denver.

In 2020 she returned to the X’s, this time painting 40,000 of them on a silvery emergency blanket to represent the roughly 40,000 people who die by gunshot wounds in the United States every year. And in a 2022 show, the X’s appeared again, 6,000 of them for the casualties caused by the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

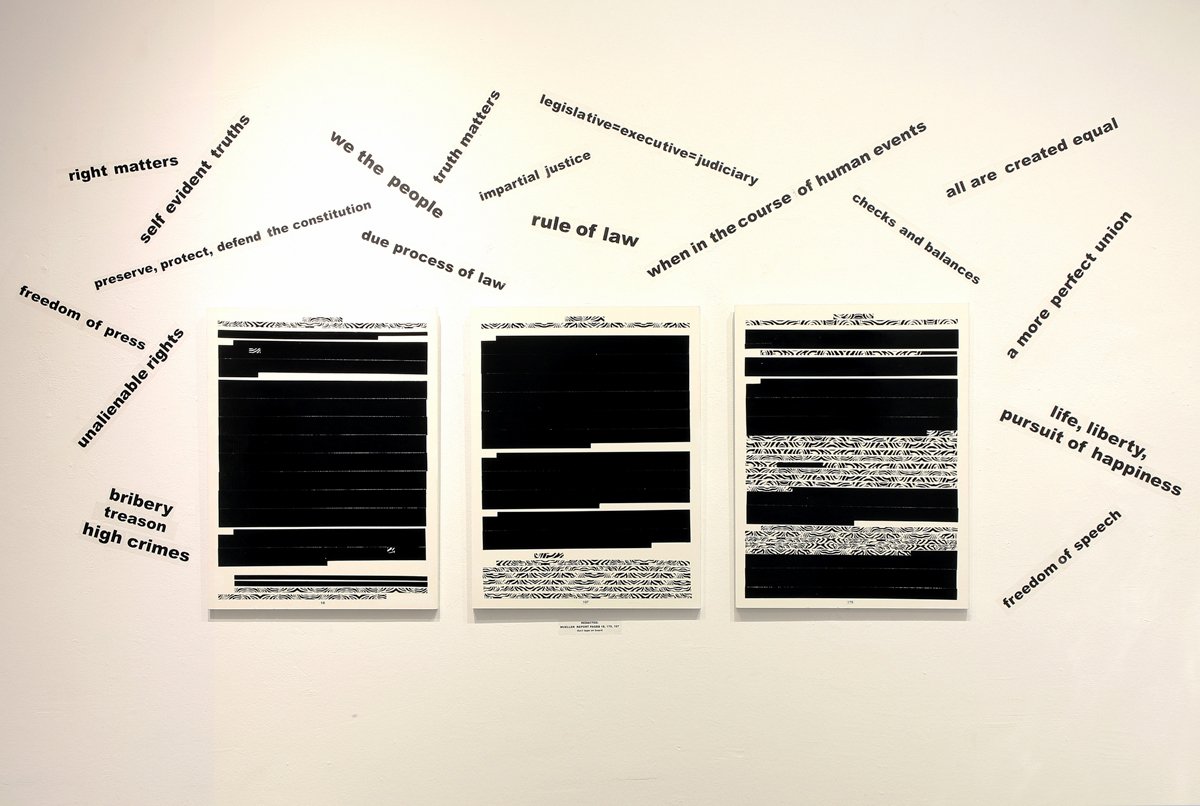

Annalee Schorr, Redactions: Mueller Report, Pages 18, 179, 197, 2020, duct tape on board, 30 x 23 inches each. Image by Marcia Ward/The Image Maker Denver.

But it’s not all death and destruction. Some of her political works have an underlying humor to them. It’s a dark humor that jabs at the absurdity of national politics, but a sense of humor, nonetheless. Like her reproductions of the Mueller Report, the 500-page investigation into Russian election interference during the 2016 U.S. presidential election. The pages are rows of black bars—all of them redacted.

A detail view of Annalee Schorr’s Shock/Awe February 4, 2003, 12 x 20 inches, TV photos. Image courtesy of the artist.

Then there are her TV photos that she started taking in 2000 during the presidential race between George W. Bush and Al Gore. As the controversially close election unfolded, Schorr set up her camera facing the television and loaded it with 36-shot film, then she sat with a shutter remote and quickly snapped photos of thirty-six different channels.

The Denver Art Museum acquired two works from this project: What's On? Wednesday, November 8, 2000, 12:30 a.m. and What’s On? Tuesday, December 12, 2000, 7:30 p.m.

Annalee Schorr, Shock/Awe April 9, 2003, 48 x 40 inches, contact sheet of TV photos. Image courtesy of the artist.

In the November piece, one TV station shows the candidates locked in a tie at 242 electoral votes each. Another reads across the top: “too close to call.” But there’s also a game show on one of the screens, and someone is about to win or lose $12,720. We also see a football game, a hockey game, a dog show, and scattered showers in the northeast.

She repeated the setup during Bush’s inauguration, throughout the Iraq War and, most recently, during the presidential debate between President Trump and Hillary Clinton.

“It’s like a time capsule,” she says.

Annalee Schorr, Fred: Homeless in Denver, 2003, 44 x 30 inches, xeroxed photo on raw cardboard. Image by DARIA.

In 2000 Schorr mounted an exhibition at the Rocky Mountain College of Art and Design (RMCAD) called Homeless in Denver. It featured massive portraits that she had taken of homeless individuals on the streets near her studio in the Baker neighborhood. Some of them gave her details about their lives, which she printed onto the portraits.

An earlier version of the show at Spark Gallery had gotten a write-up in The Denver Post, and when Schorr turned up to give her artist’s talk at RMCAD to what she thought would be “ten, maybe fifteen students,” she instead found a crowd closer to seventy-five.

Annalee Schorr, Charles: Homeless in Denver, 2003, 44 x 30 inches, xeroxed photo on raw cardboard. Image by DARIA.

“There were people there who were furious at me for ripping these people off, thinking I was selling their pictures for big bucks. There were people there who wanted to tell me how stupid I was—didn't I know that each of these people had a Cadillac parked around the corner? And there were people there who acted like I'd solved the problem of homelessness and thanked me,” Schorr says, laughing at the memory. “It was almost a riot.” (She has since started an ongoing collaboration between Spark and the Colorado Coalition for the Homeless).

A view of Annalee Schorr’s studio work table. Image by DARIA.

At this current political moment, Schorr is in a kind of limbo. Spark just fully moved into their new home, but she doesn’t have any big shows coming up. She still goes to the studio every day to work—she’s really into magnetic sheets right now—and she wants to do something about the recent election. But she’s not sure what. Or how.

A view of Annalee Schorr’s studio. Image by DARIA.

“The morning after the election, I couldn't believe it. We'd had some snow that morning, and the trees all had leaves on them still. I took a broom out and pounded the hell out of all the trees, and that helped some,” Schorr says.

“All of it has always been serious,” she says about her political work. “But the implications now just seem overwhelming. It's sort of like—I just don't know where to begin.”

Parker Yamasaki (she/her) is a western states arts writer based in Lafayette, Colorado. She is a culture reporter for the statewide, nonprofit newsroom The Colorado Sun. She is also a freelance critic. Her work has been published in The Chicago Reader, Newcity Chicago, Austin Monthly, and various online publications.