Women's Work is Never Done | To See Takes Time

Jasmine Dillavou, Charis Fleshner, Carrie Shiffrin: Women's Work is Never Done

Kathryn Oberdorfer: To See Takes Time

Art Gym Denver

1460 Leyden Street, Denver, CO 80220

September 25-October 19, 2025

Admission: free

Review by Paloma Jimenez

Manicured nails, a lovely blouse, tidy house, serene expression, and freshly scented body. Or perhaps a repressed sarcastic comment, drunkenly smeared lipstick, avoiding eye contact with the dust bunnies, chipped fake nails, stained underwear, and bed rotting. Those are two sides of the same coin (in a considerably vast and armored vault) that’s inscribed with the question: how do I want to be a woman today?

An installation view of the exhibition Women's Work is Never Done at Art Gym. Image by Paloma Jimenez.

It’s a different answer for every woman depending on the day, mood, and general state of society. No matter the path, navigating the constantly shifting demands of womanhood is wonderfully and frustratingly laborious. Art Gym’s current exhibition tackles the details of this emotional, material, and bodily labor in Women’s Work is Never Done, featuring the art of Carrie Shiffrin, Charis Fleshner, and Jasmine Dillavou.

An installation view of Women's Work is Never Done with two paintings by Carrie Shiffrin in the center. Image by Paloma Jimenez.

Carrie Shiffrin’s portraits of glamorous women burst with varying emotions, from spontaneous excitement to thinly veiled judgement; however, the fluid strokes of saturated paint are not without an underlying darkness. Neon streaks and deep shadows morph a smile into a grimace.

Carrie Shiffrin, This shlak?, watercolor and ink on paper. Image by Paloma Jimenez.

In This shlak?, Shiffrin depicts two stylish gallery hoppers, draped in jewel tones and adorned with bold accessories. Their white hair flows with effortless panache. Despite such vibrant outfits, their animated frowns assess their surroundings. They’ve seen it all, glancing sideways with mouths open in midsentence, as if asking the viewer, “Is there any original art left these days?”

Carrie Shiffrin, Refs you suck!, watercolor and ink on paper. Image by Paloma Jimenez.

The women in Shiffrin’s work appear to prefer the louder, less controlled spaces where unrestrained expression reigns. Refs you suck! features a low angle view of two exasperated older women, mouths contorted to fling profane words at the referees. It’s a painting with loud lights, loud colors, loud energy, and unapologetically deep wrinkles. Shiffrin’s senior women have aged out of the male gaze’s surveillance, instead reveling in their own discerning taste and joie de vivre.

Carrie Shiffrin, Girl Dinner, gouache and ink on paper. Image by Paloma Jimenez.

The least lifeless painting by Shiffrin—and intentionally so—titled Girl Dinner is also the only painting to depict younger women. Faced with a table full of uneaten cake houses, their perfectly pretty faces somberly examine each other’s plate progress. The hairdos and outfits reference the 1950s and ‘60s, from the youth of the older women, who in the other paintings appear more than okay with leaving societal expectations behind.

Jasmine Dillavou, Her Covered Mouth, Her Exposed Truth, lipstick on canvas. Image by Paloma Jimenez.

Jasmine Dillavou confronts the labor and magic of feminine stories in mixed media works, employing the actual materials of beauty: lipstick, acrylic nails, and “magical herbs.” Lipstick marks whisper against the canvas in works such as Her Covered Mouth, Her Exposed Truth. The pink and scarlet smears move around with a rhythm reminiscent of spoken language, without revealing any of the story’s details.

Jasmine Dillavou, Fought Forever, lipstick on panel. Image by Paloma Jimenez.

In other instances, Dillavou’s lipstick mark-making is less tender and leans towards a more unsettling narrative. In Fought Forever, Dillavou drags the red downward, and the concentrated splatter in the bottom left corner reads like a violent period at the end of a disturbing sentence. The performative act of painting with lipstick brings to mind the horror movie trope of women messily applying color to areas well beyond the outline of their lips. (Spoiler alert: they’re about to do something irreversible.) You cannot have beauty without the lingering presence of horror and decay.

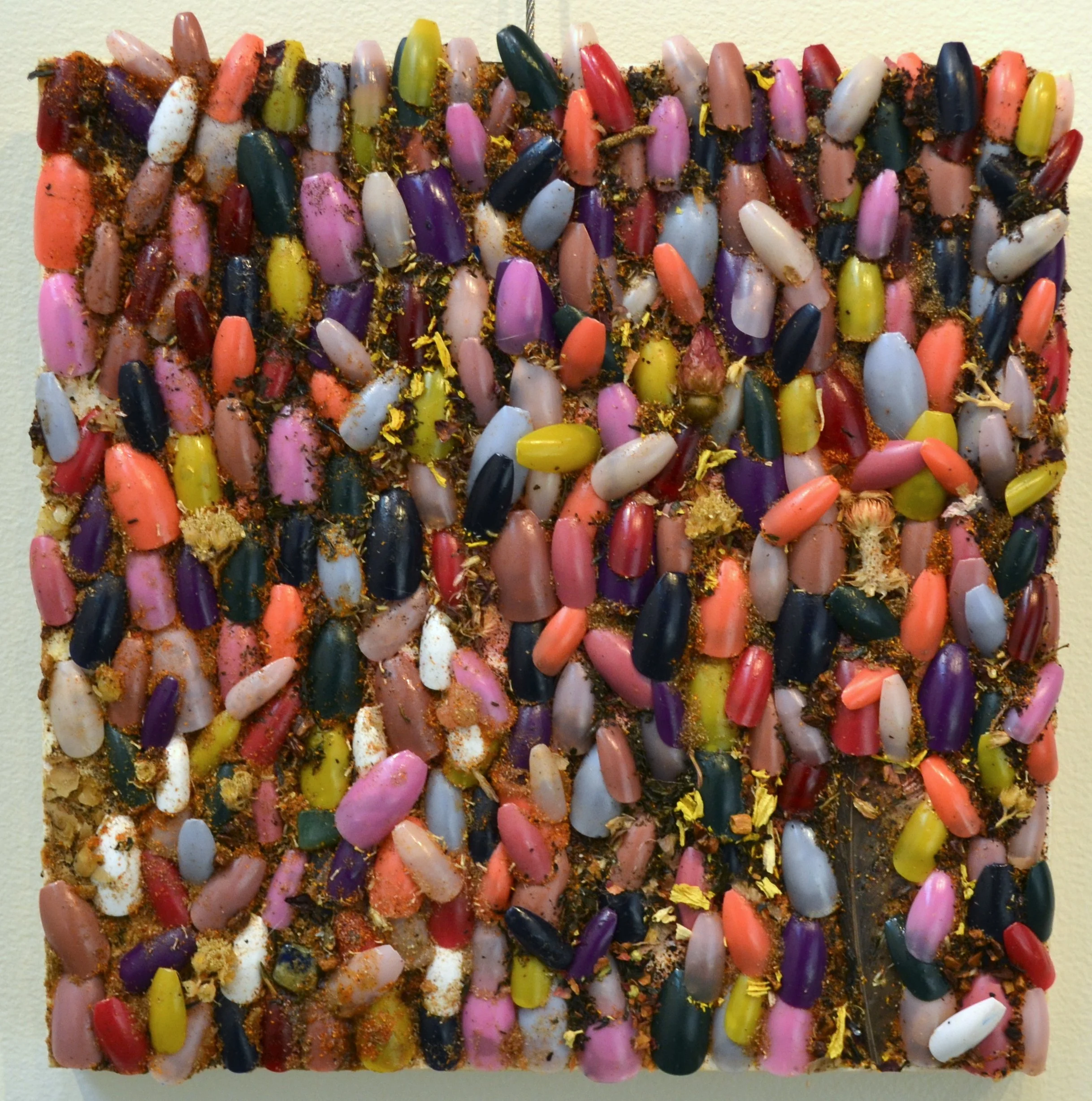

Jasmine Dillavou, Digging your way out, acrylic nails and herbs. Image by Paloma Jimenez.

Jasmine Dillavou, Dirt Under Nails I, acrylic nails, bones, and magical herbs. Image by Paloma Jimenez.

In a series of works using acrylic nails, Dillavou explores the mystical, primordially violent nature of feminine rituals. Acrylic nails, extending one’s fingers into claws, can beckon to come hither or strike in defense. The frameless works with nails and bones protruding out from the edges are the most striking. Digging your way out layers clashing nail colors with crumbled herbs and flowers. Black satin thumb nails scatter around the panel like decomposer beetles. In Dirt Under Nails I, pastel pink nails clatter together amongst a handful of embedded animal bones. As Wallace Stevens so aptly put it, “Death is the mother of beauty.”

Three works by Charis Fleshner in the exhibition Women's Work is Never Done at Art Gym. Image by Paloma Jimenez.

Along with beauty rituals, the clothes we wear can tell an endlessly customizable story of womanhood. But an outfit is one thing, and laundry is a whole other beast. When people come over, we rush to shove worn undergarments and salty, sweat-stained t-shirts into the hamper, as if to signal: My body is always clean. I do not sweat, shit, or participate in any other base activities that might produce unseemly stains and odors. Charis Fleshner exposes this vulnerable feeling in her series of colored pencil drawings of dirty laundry, from her own life and from fellow women artists.

Charis Fleshner, She didn’t mean anything to me, colored pencil on paper. Image by Paloma Jimenez.

Charis Fleshner, Up your meds, colored pencil on paper. Image by Paloma Jimenez.

The drawing titled She didn’t mean anything to me hints at the more emotional memories that clothing can ignite. A striped red and white garment hangs limply from a chrome hand towel rack; misplaced and somewhat lonely on the wall. Up your meds expresses a similar feeling of isolation. A yellowed pair of socks and a small teal garment sit at the bottom of an otherwise empty wire basket. Sometimes a laundry basket is empty because the laundry is freshly cleaned, other times it’s because you haven’t changed out of your clothes in days.

Charis Fleshner, Shhhhhhhhhhh, colored pencil on paper. Image by Paloma Jimenez.

The more imposing tower of laundry in Shhhhhhhhhhh feels endless and the perspective of the work isn’t entirely clear. Plaids, solids, and stripes tumble towards the viewer in a jumbled and disorienting mess; the secrets are piling up. It’s not the viewer’s job to sort and clean through Fleshner’s dirty laundry, but rather to witness and respect her honesty. Transforming the more unbearable aspects of life into something beautiful has always been a woman’s specialty.

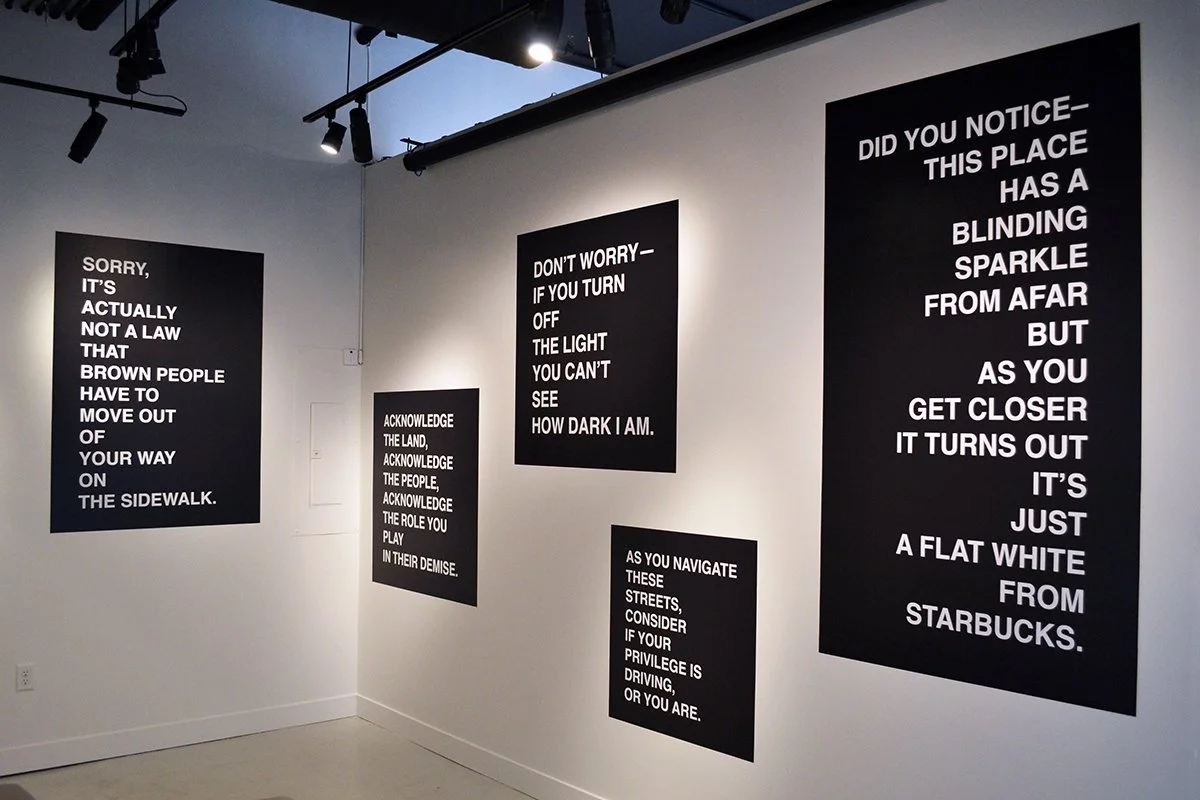

An installation view of Kathryn Oberdorfer’s exhibition To See Takes Time in the Leyden Jar Gallery at Art Gym. Image by Paloma Jimenez.

In the Leyden Jar Gallery, towards the back of Art Gym’s work space, Kathryn Oberdorfer’s solo exhibition To See Takes Time favors looser lines and an abstract expressionist approach to composition. The paintings are not splatter art (thankfully), but they do seem to delight in the complexity of a well-observed spill and unexpected conglomerations.

Kathryn Oberdorfer, In the Gardens, acrylic, pastel, charcoal, and collage on canvas. Image by Paloma Jimenez.

Despite the many layers of textured acrylic, pastel, charcoal, and collage, In the Gardens retains a freshness of color. Safety vest orange plays well with the murkier olive greens and smudged charcoal lines. A swatch of primary yellow at the top keeps the gradients from sliding too smoothly into one another; you cannot have good abstraction without disruption.

Kathryn Oberdorfer, Nightfall, acrylic and pastel on canvas. Image by Paloma Jimenez.

Similar in palette, Nightfall moves with less texture and instead uses lines to sculpt out different visual planes. The dusty purple that occupies much of the canvas masks previous layers, as if another layer is yet to be added. But Oberdorfer resists a predictable resolution to the painting, and our perception remains slightly obscured.

Works by Kathryn Oberdorfer in her exhibition To See Takes Time. Image by Paloma Jimenez.

In a piece for The Washington Post, abstract painter Amy Sillman asks, “Can an abstraction be read as a form of ecstatic folk art for our comrades? Can we expose, or reverse, our rapid unspooling by the rearrangement of our uncomfortable parts?” [1]

The artists in both exhibitions at Art Gym reflect on and reinvent the uncomfortable, messily contradictory aspects of life. In an increasingly isolated social landscape, honest art serves as a checkpoint for human connection.

Paloma Jimenez (she/her) is an Editorial Coordinator at DARIA and an artist, writer, and teacher. Her work has been exhibited throughout the United States and has been featured in international publications. She received her BA from Vassar College and her MFA from Parsons School of Design.

[1] Sillman, Amy, “Spring: Abstraction as ruin,” The Washington Post, 18 March 2024, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/interactive/2024/artist-amy-sillman-spring-animated-video-humor-absurdity/.