Traitor, Survivor, Icon

Traitor, Survivor, Icon: The Legacy of La Malinche

Denver Art Museum

100 W. 14th Avenue Parkway, Denver, CO 80204

February 6-May 8, 2022

Curated by Victoria I. Lyall and Terezita Romo, with Matthew H. Robb

Admission: Free with admission—Adults: $13 for Colorado residents, $18 for non-residents; Seniors, Students, & Military: $10 for Colorado residents, $15 for non-residents; Youth 18 and Under and Members: Free.

Review by Madeleine Boyson

Around 1503-1507, a Nahua girl later known by various names—Malina, Malinalli Tenépatl, Doña Marina, Malintzin, La Malinche—was born on Mexico’s Gulf coast. Between 1519 and her death in 1529-30, she was trafficked to and enslaved by Spanish colonizers, brokered an alliance between the Spanish and the Indigenous Tlaxcalan community, witnessed the Spanish-Aztec war and subsequent fall of the latter’s empire, and bore two children by conquistadors. Malinche was a principal, if overlooked actor during this period, garnering a complicated, yet impassioned heritage of criticism and admiration as both a traitor and “the mother of Mexico.”

An installation view of the exhibition Traitor, Survivor, Icon: The Legacy of La Malinche at the Denver Art Museum. Image courtesy of the Museum.

In Traitor, Survivor, Icon: The Legacy of La Malinche at the Denver Art Museum (DAM), on view through May 8, Victoria I. Lyall, who is the Jan and Frederick Mayer Curator of Art of the Ancient Americas at the DAM, independent curator Terezita Romo, and Matthew H. Robb, Chief Curator of the Fowler Museum, UCLA, present the first ever comprehensive art exhibition examining Malinche’s significance. [1]

The exhibition illustrates her life through a stunning 68 works by 38 artists from Mexico, the United States, and France, encompassing five centuries worth of material that exemplifies Malinche’s contentious and consequential impact. Yet the show is as much an historiography lesson as it is an art exhibition: venturing through Malinche’s considerable visual record, viewers encounter not only her personal history, but the ways in which her narrative has been culturally codified over the last five hundred years.

A view of the timeline for Malinche in the Traitor, Survivor, Icon exhibition and two works in show, including Sandy Rodriguez’s Mapa for Malinche and our Stolen Sisters, dedicated to Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW) and families, 2021, hand-processed watercolor and 24k gold on amate paper. Image courtesy of the Denver Art Museum.

Sandy Rodriguez’s remarkable Mapa for Malinche and our Stolen Sisters (2021) opens the show—a hand-processed watercolor and 24k gold amate paper map of Mexico and the Southern U.S., dedicated to Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW) and their families. Rodriguez’s cartography locates Malinche’s life and superimposes a red handprint record of present-day stolen MMIW, who proxy the nineteen girls trafficked alongside Malinche in 1519. The map creates a further dialogue between the sixteenth and twenty-first centuries: an accompanying QR code pinpoints another nineteen MMIW on a digital human trafficking map and draws parallels between Malinche and her missing contemporary sisters.

Sandy Rodriguez, Mapa for Malinche and our Stolen Sisters, dedicated to Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW) and families, 2021, hand-processed watercolor and 24k gold on amate paper. Image by Madeleine Boyson.

A curatorial video follows, outlining the chronological, cultural, geographical, and historical contexts of the exhibition. Malinche’s visual tradition is then framed in five themes: La Lengua/The Interpreter, La Indígena/The Indigenous Woman, La Madre de Mestizaje/The Mother of a Mixed Race, La Traidora/The Traitor, and “Chicana”/Contemporary Reclamations, a structure that provides viewers with an historiography intending to “...examine the conditions that have led to the appropriation and adaptation of her image for the purposes of enacting cultural and political identities.” [2]

An installation view of Jesús Helguera’s La Malinche, 1941, oil paint on canvas, 6 feet 9 inches x 5 feet 7 inches. A collaboration between Carolina Performance, a socially responsible company whose mission is to preserve the cultural heritage of their country, and the Quintana Corral Family, in honor of the roots and mixed-race heritage of our Mexican people. © and courtesy of Calendarios Landin. Image courtesy of the Denver Art Museum.

Historiography—a history of history—is a “meta-discourse”: “a ‘narrative about narratives’ whose subject matter is other works of history, rather than historical events themselves.” [3] Historiography is useful in part because “...there is not necessarily a simple relationship between ‘the past’ and the way it is written down and remembered,” or in this case, the way it is visually rendered. [4] Traitor, Survivor, Icon illustrates the complex exchange between Malinche’s factual history and how she has been spoken of or depicted since, highlighting an artistic record with conflicting narratives towards myriad ends.

The curators highlight Malinche’s linguistic abilities in La Lengua (she spoke Nahuatl, Mayan, and Spanish). Though there exists no record of her in her own voice, Malinche found influence in translating for Hernán Cortés, who first described her as “la lengua que yo tengo” (the tongue I own). Jesusa Rodríguez’s video La Conquista según La Malinche (The Conquest according to Malinche) (1985-99) performs Malinche’s voice as a cheeky news correspondent and weaves her perspective into a captivating, satirical commentary utilizing slang, repartee, and double entendres.

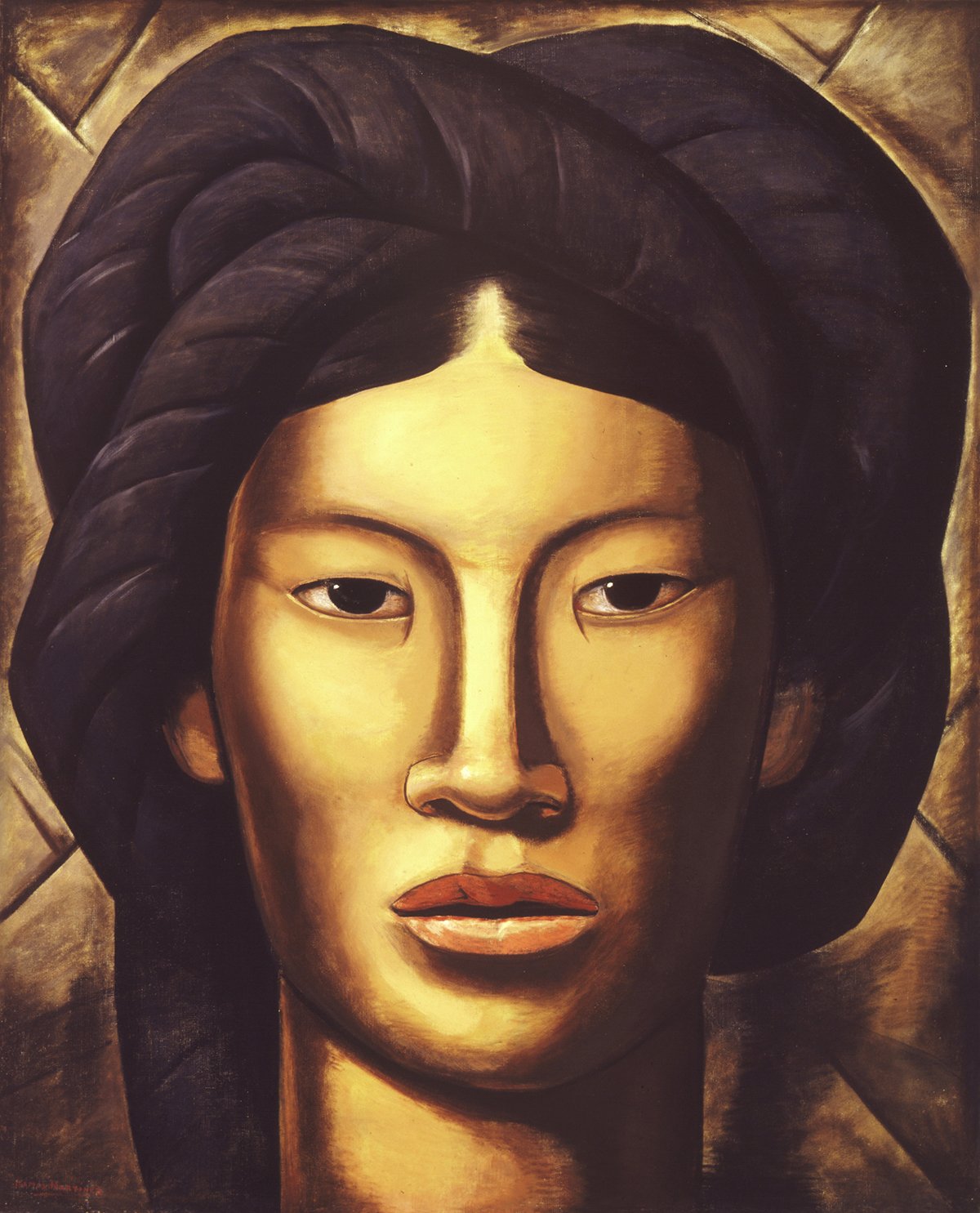

Alfredo Ramos Martínez, La Malinche (Young Girl of Yalala, Oaxaca), 1940, oil paint on canvas, 50 × 40.5 inches. From the collection of the Phoenix Art Museum: museum purchase with funds provided by the Friends of Mexican Art, 1979.86. ©The Alfredo Ramos Martínez Research Project, reproduced by permission. Image courtesy of the Denver Art Museum.

In La Indígena, visitors confront Malinche’s image and identity as an Indigenous woman and the “racialized standards of beauty in depictions” of her over the centuries. [5] Malinche gazes unwaveringly in Alfredo Ramos Martínez’s La Malinche (Young Girl of Yalalag, Oaxaca) (1940), which associates her with Zapotec women in a striking contrast to Jesús Helguera’s fair-skinned, Golden Age film star Malinche on the opposite wall. Each manages to indicate her indigeneity, however—Martínez highlights a traditional Zapotec hair-wrapping technique while Helguera’s work features a naming huipil (tunic), sandals, and braided hair.

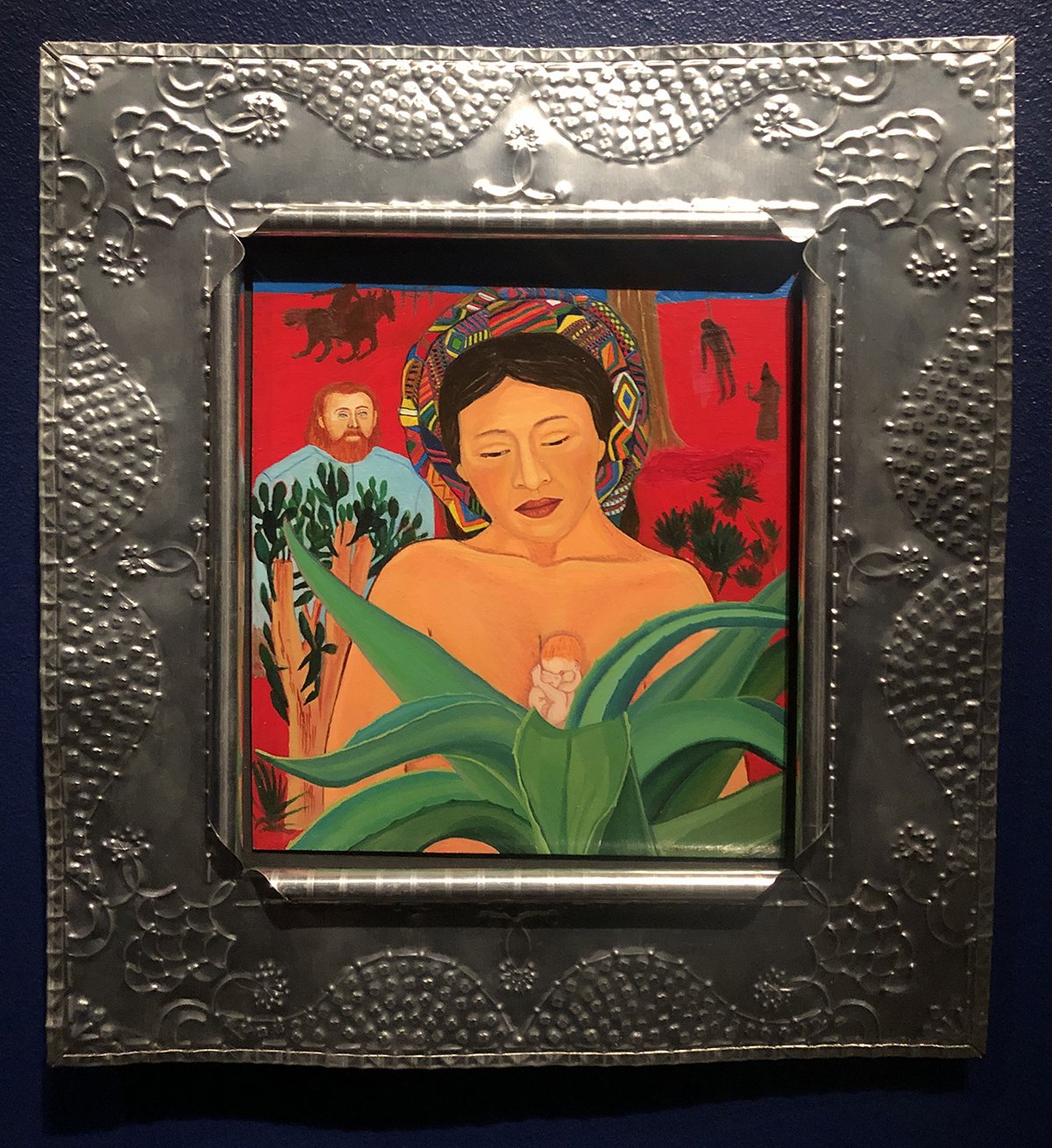

Santa Barraza, La Malinche, 1991, oil paint on metal, 10.875 x 9.875 inches. Private collection, © Santa Barraza. Image by Madeleine Boyson.

Jorge González Camarena, La pareja (The couple), 1964, oil paint on polyester and fiberglass, 7 feet x 48.25 inches. Private collection, © Fundación Cultural Jorge González Camarena, AC. Image courtesy of the Denver Art Museum.

La Malinche by Santa Barraza (1991) is a tiny oil on metal near Jorge González Camarena’s towering La pareja (The couple) (1964) in La Madre del Mestizaje. Where Malinche is a larger-than-life matriarch in the latter, she becomes an introspective mother in Barraza’s piece, eyes cast over a fetus that emerges simultaneously from her chest and an aloe plant. Cortés stands in the middleground, off-setting a background of violence and Malinche’s foregrounded infant nation. Both works speak to this section’s investigation of mestizaje (“the mixing of the races”) and a “mythologized” Mexican national identity borne of Malinche’s union with Cortés and the birth of their son, Martín. [6]

Teddy Sandoval, La Traición de Malinche (Malinche’s betrayal), 1993, watercolor on treated canvas, 10.5 x 13.5 inches. Courtesy of Paul Polubinskas, from the estate of Teddy Sandoval. Image courtesy of Elon Schoenholz Photography and the Denver Art Museum.

La Traidora and Chicana: Contemporary Reclamations illustrate the most conflicting accounts in Malinche’s historiography—the term malinchista, derived from her name, refers to “a cultural traitor,” a narrative that endured well into the 1970s, “when Chicana artists reclaimed and rehabilitated her identity.” [7] Teddy Sandoval depicts Malinche and Cortés as disembodied heads in the watercolor La Traición de Malinche (Malinche’s betrayal) (1993). Their tongues wiggle towards each other, connoting their linguistic and sexual relationship, while a whole-bodied Aztec warrior dies with a sword to the heart behind them. Two eyes—perhaps the eyes of history—float behind this surrealist tangle of vines and betrayal.

Annie Lopez, Sold as a Slave, 1995, reprinted in 2021, cyanotype. Image by Madeleine Boyson.

In contrast, Annie Lopez humanizes Malinche’s life in Sold as a Slave (1995, reprinted 2021) by labeling family photographs from the 1940s with the phrases “sold as a slave,” “interpreter and companion,” and “survivor.” In the artist’s words: “Upon first glance, you see nothing but their outward seductive appearance, but they are actually intelligent, emotional, and loving beings.” [8] The three women strike genuine poses you might see today, linking them to the present and creating an ancestral throughline from Malinche to Lopez and beyond: women who do what they can in the circumstances dealt to them.

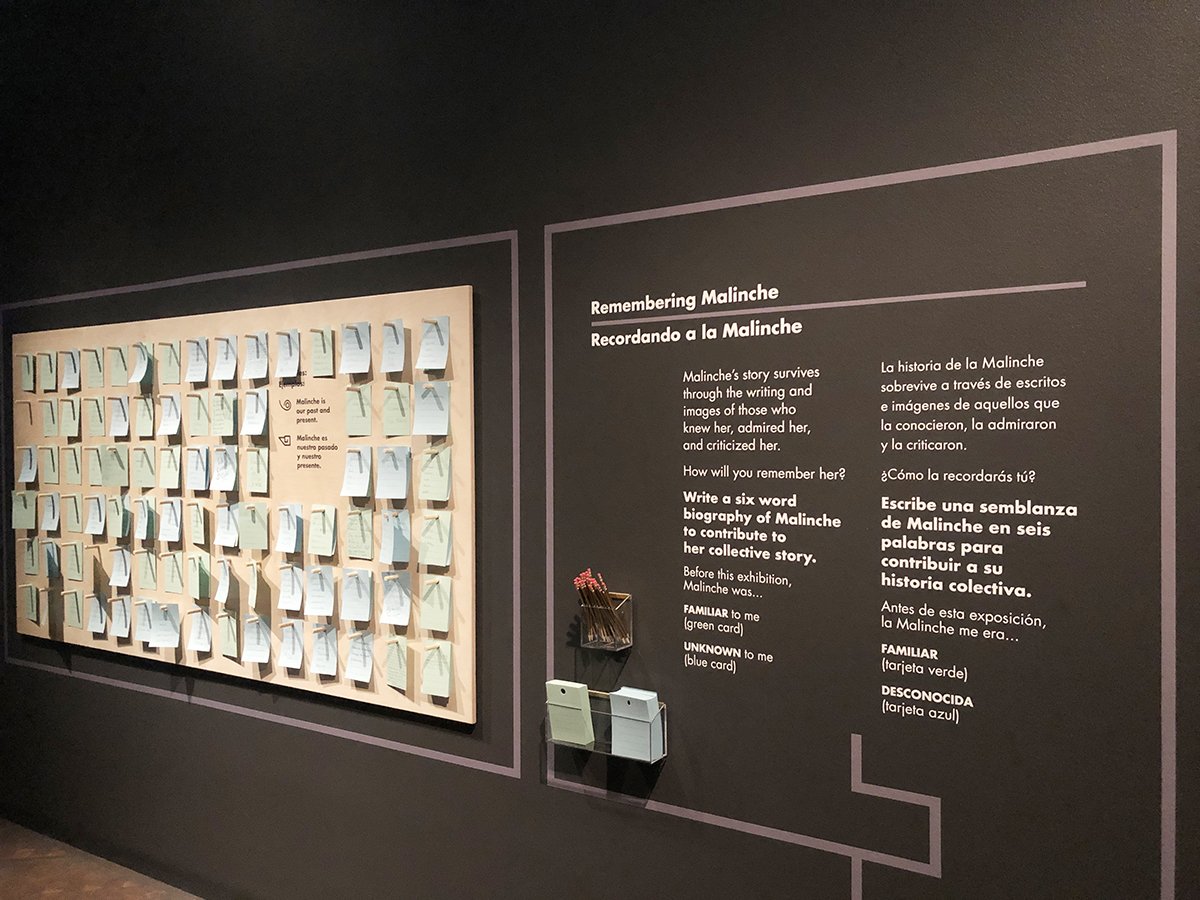

A view of the interactive wall “Remembering Malinche / Recordando a la Malinche” in Traitor, Survivor, Icon: The Legacy of La Malinche at the Denver Art Museum. Image by Madeleine Boyson.

The exhibition ends with a final lesson in Malinche’s historiography: that her legacy survives in every narrative—positive or negative, complicated or simplified. Visitors are invited to memorialize Malinche in a six-word biography “to contribute to her collective story.” The result is a wall full of new historical interpretations about an enslaved Indigenous linguist who stood at a hinge in history.

Because it is in the hands, mouths, and art of people—the curators seem to conclude—Malinche’s historiography will forever evolve, grow, and, gratefully, persist.

Madeleine Boyson is a Denver-based writer, artist, lecturer, and curator whose work concentrates on American modernism, natural photography, and (dis)ability studies. She holds a BA in Art History and History from the University of Denver and volunteers as development director for the arts platform Femme Salée.

[1] After closing at the DAM on May 8, 2022, the exhibition will travel to the Albuquerque Museum (on view June 11-September 4, 2022) and then to the San Antonio Museum of Art (on view October 14, 2022-January 8, 2023). Additionally, other art exhibitions about La Malinche will open next month in Denver—Malinalli on the Rocks is on view at Museo de las Americas from March 17-July 23, 2022, and Malintzin: Unraveled and Rewoven, a collaboration between Next Stage Gallery, the Denver Art Museum, and the Latino Cultural Arts Center, will be on view from March 31-May 1, 2022.

[2] From the exhibition press release: “Denver Art Museum to Present First Comprehensive Exhibition Exploring the Life and Legacy of Malinche, the Iconic Indigenous Young Woman at the Heart of the Spanish and Aztec War (1519-1521), https://www.denverartmuseum.org/en/press/release/la-malinche-premiere, accessed February 20, 2022.

[3] Jeremy D. Popkin, From Herodotus to H-Net: The Story of Historiography (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016), 5. In this case, the “other works of history” are the art objects in the exhibition, primary and secondary sources developed over the centuries to codify certain narratives about La Malinche.

[4] Ibid, 4.

[5] From the exhibition wall text.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.