Singularity / Reflectivity

Andrew Roberts-Gray: Singularity | Collin Parson: Reflectivity

Michael Warren Contemporary

760 Santa Fe Drive, Denver, CO, 80204

May 13–June 21, 2025

Admission: free

Review by Nina Peterson

Installed concurrently at Michael Warren Contemporary, Andrew Roberts-Gray’s Singularity and Collin Parson’s Reflectivity create a dialogue between two Colorado-based artists who examine the relationship between art, technology, and perception in different media: Andrew Roberts-Gray in painting and Collin Parson in installation and sculpture. Experienced together, the works in the gallery implicate viewers in the fraught discourses surrounding contemporary technologies such as social media and artificial intelligence.

An installation view of the exhibitions Singularity and Reflectivity at Michael Warren Contemporary. Image by Nina Peterson.

Gallerists Mike McClung’s and Warren Campbell’s curation calls attention to the formal and conceptual resonances between the works. For example, the motif of the grid—and its relationship to digital culture—recurs in both artists’ exhibitions.

Collin Parson, Untitled (from the Reflection Series), mirrored acrylic, LED, and panel. Image by Nina Peterson.

A detail view of Collin Parson’s Untitled (from the Reflection Series), mirrored acrylic, LED, and panel. Image by Nina Peterson.

Parson’s Untitled (from the Reflection Series) is a circular mirrored acrylic panel, out of which is cut a warped grid of dots and squares. A blue glow of LED light emanates from behind the negative spaces of the squishy grid. Parson stretched and elongated the square holes so that the grid appears to slough and slide, loosening the strict pattern and creating an optical illusion in which a bulge seems to strain against the mirrored surface, pendulously protruding into the viewer’s personal space. Installed across from the gallery window wall, Untitled (from the Reflection Series) pulls the sidewalks of Santa Fe Drive into the space of Michael Warren Contemporary, as if the bulge is the street bursting into the gallery.

Andrew Roberts-Gray, Blue Dye, oil on linen. Image by Nina Peterson.

There’s another grid-in-a-circle in Roberts-Gray’s Blue Dye. The pattern takes painted form as a disc floating in a landscape. Linear perspective shows the gridded disc, which occupies much of the left half of the composition, receding into the picture plane.

An installation view of Collin Parson’s exhibition Reflectivity with reflections of Roberts-Gray’s work at Michael Warren Contemporary. Image by Nina Peterson.

McClung’s and Campbell’s curatorial savvy is apparent when observing Parson’s Reflection Towers—three cuboid acrylic structures that stand vertically in heights of five, seven, and eight feet. When standing just to the left of the three sculptures and facing the gallery’s back wall, the view joins the two artists’ works: Roberts-Gray’s Blue Dye reflects in the seven-foot pillar, and hanging on the back wall is Parson’s Untitled (from the Reflection Series). From this angle, it looks like the works appear parallel to each other, as if on the same plane.

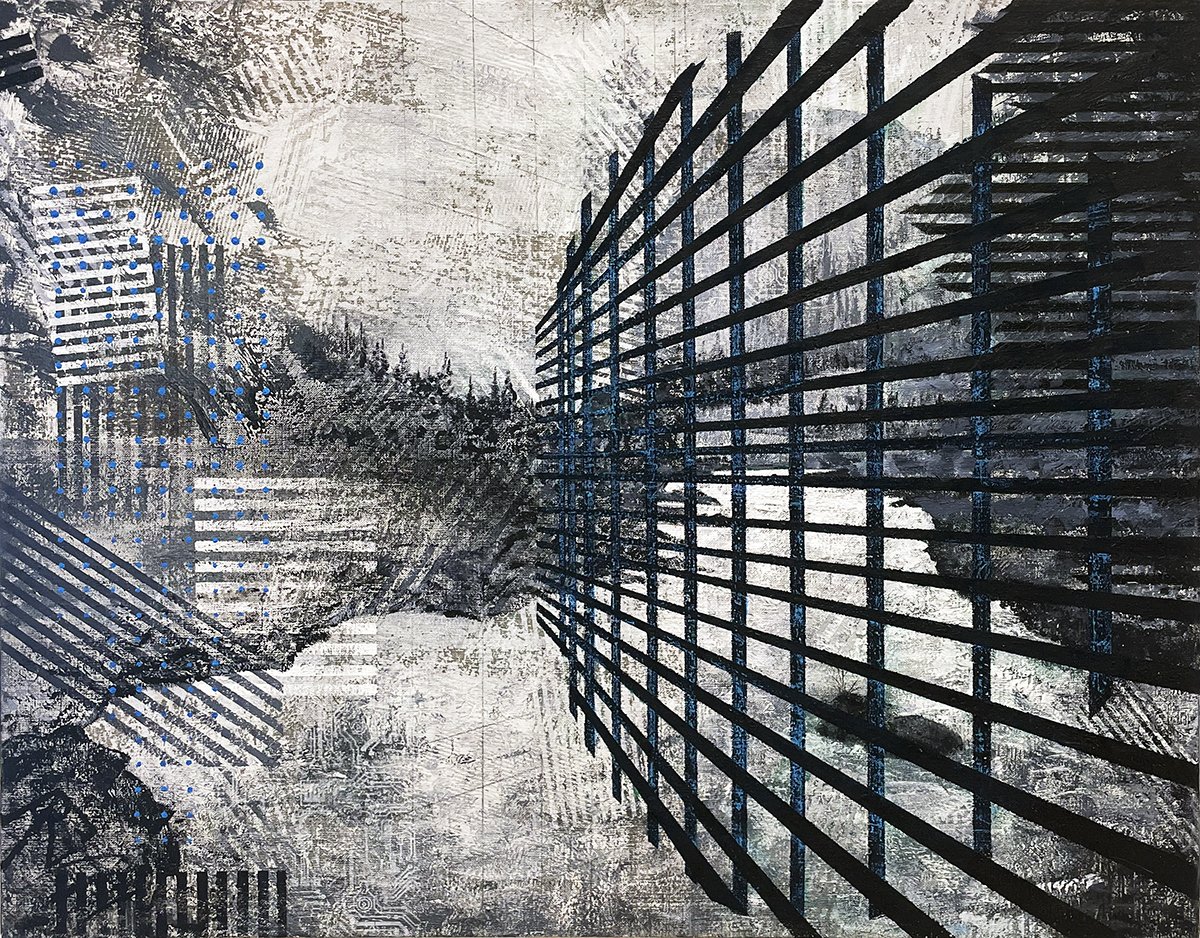

Andrew Roberts-Gray, Black Array, oil on linen. Image by Nina Peterson.

In addition to highlighting how both artists play with the grid as a visual motif, the exhibitions raise questions about the relationship between the aesthetics of the grid and contemporary social life. The grid is a tool for making a claim to aesthetic modernity, for organizing data, and for structuring life itself. [1] Formally, it is a pattern of rigid, intersecting vertical and horizontal lines set at regularly spaced intervals. Structurally, it is a manifestation of power (in the sense of social relationality and governance and in the sense of a network of electrical plants and transmission lines).

An installation view of Collin Parson’s exhibition Reflectivity at Michael Warren Contemporary. Image by Nina Peterson.

The electrical grid powers the use of computers and the internet, and artificial intelligence puts massive strain on the power grid. [2] The grid is therefore central to digital culture, which is another point of thematic connection between Reflectivity and Singularity. In particular, Parson’s work engages selfie culture, and Roberts-Gray’s paintings represent a theoretical concept related to AI.

Collin Parson, Untitled (from Interference Series), printed acrylic. Image by Nina Peterson.

I chatted with Mike McClung as I experienced Reflectivity, and he noted that the numerous mirrored surfaces would no doubt attract selfie-taking. Indeed, it is difficult to not take a selfie while photographing Parson’s work. And that is part of the point. His work involves the viewer, raising questions about an individual’s position in space and in relation to others who share that space.

An installation view of Collin Parson’s exhibition Reflectivity at Michael Warren Contemporary. Image by Nina Peterson.

Parson cites Robert Irwin and James Turrell, artists affiliated with the Light and Space movement of the 1960s and 1970s in California, as key influences on his practice. [3] Like his predecessors, Parson takes a phenomenological approach to artistic creation. That is, his works use effects of light and its interplay with space to shape viewer perception. The title of Parson’s exhibition, Reflectivity, no doubt refers to the predominant phenomenon at play in the exhibition: the effect of mirrored surfaces throwing light and images back at the viewer. I’d say it also names a possible outcome of engaging with the work: we might become reflective—that is, more thoughtful, or capable of looking inwards—by interfacing with this installation.

Collin Parson, Untitled (from the Reflection Series), mirrored acrylic, LED, and panel. Image by Nina Peterson.

But there’s also the question of how this effect of Parson’s work (its quasi-conscriptive integration of the individual self into the surface of the objects on view) intersects with contemporary social practices and economies of taking selfies and posting them online. What does it mean when a viewer takes an image of themselves in Parson’s work and enters it into the visual and material economies of social media, administered and governed by tech corporations that profit from the restructuring of the self under neoliberalism? [4]

An installation view of Collin Parson’s exhibition Reflectivity at Michael Warren Contemporary. Image by Nina Peterson.

There is an abundance of cultural and scholarly discourse surrounding the selfie as a mode of representation and its relationship to social media technologies that shape human perception of self and others. Tech corporations capitalize on aspirations towards the status of elite influencer, a subjectivity that media scholar Grant Bollmer and art historian Katherine Guinness theorize as modelled off of and enacted in the mode of a vertically integrated corporation. [5] Integral to this kind of economy of the self is algorithmic determination, through which social media giants control what and how users see.

Andrew Roberts-Gray, Wavelength, oil on linen mounted to panel. Image by Nina Peterson.

Questions of algorithmic determination—the way that the technical procedures in digital media condition human behavior, perception, and interaction—are implicit in Andrew Roberts-Gray’s exhibition Singularity. In these oil paintings, symbols of computer technology such as a series of numbers that look like digital rain and geometric, interlacing linear patterns that recall circuit boards appear alongside grids in expressive naturescapes. These designs evoke Sci-Fi imaginaries and virtual reality, suggesting that digital technology is already embedded in or determinative of human visions of the “outside” world.

Andrew Roberts-Gray, Harlequin Evening, oil on linen. Image by Nina Peterson.

Across this body of work, Roberts-Gray uses an array of techniques to suggest atmospheric qualities and render landscapes. Some areas look like grattage (a method of creating an implied texture by applying paint to a surface overlaid onto an actual texture, then scraping the paint away and leaving a two-dimensional record of the tactility below). [6] In other places, dry brush creates a mottled effect, suggesting mist or the roughness of stone.

Andrew Roberts-Gray, Cloud Forest, oil on linen. Image by Nina Peterson.

In the painting Cloud Forest, a stream flows over rounded rocks, a mountain slope rises in the left background, and a forest of pines echoes it on the right. At the top of the hill and throughout the blue sky, grattage-like linear arrangements coalesce into circuit board ghosts.

Andrew Roberts-Gray, Diameter 6, oil on linen mounted to panel. Image by Nina Peterson.

In Diameter 6, grids of numbers flit in and out of legibility just at the surface of the canvas. Though it isn’t binary code, the strict columns and rows of paired numbers evoke a computer screen animated with programming sequences. These images help to create the modulated, scumbled surface of river rock and hillsides as well as the atmospheric qualities of air.

A detail view of Andrew Roberts-Gray’s Diameter 6, oil on linen mounted to panel. Image by Nina Peterson.

Jutting into this painting from the left, a heavy black bar disrupts the atmospheric perspective at work here. It is an impenetrable flatness—a blockade to further viewing of this picturesque scene. This black bar interjects abstraction into the naturalism of this landscape, calling attention to the materiality of the paint and the constructedness of the picture. Paired with the number grids, it makes us think about how technology (the technology of artmaking as well as computer technologies) mediates a viewer’s relationship to the world, and to seeing itself.

Andrew Roberts-Gray, Singularity, oil on linen. Image by Nina Peterson.

While the title of Parson’s exhibition names the predominant perceptual phenomenon at play in his series, the name of Roberts-Gray’s show directly links his work to AI. “Singularity” is a term that posits an imminent rise in superior machine intelligence that will supplant human ability to acquire and apply knowledge, thereby inaugurating a post-human era. In a 1993 article titled “The Coming Technological Singularity: How to Survive in the Post-Human Era,” science fiction writer and computer scientist Vernor Vinge asserts the stakes of such a soon-to-be-realized shift: the very continuity of human life. [7]

An installation view of the exhibitions Singularity and Reflectivity at Michael Warren Contemporary. Image by Nina Peterson.

These exhibitions prompt consideration of how art and computer technologies shape individual and collective behavior and interaction with the external world. Using techniques that play with optical perception or that demand close looking, Parson and Roberts-Grey ask viewers to think about how these technologies already shape our experiences and our relationships to each other and our environments in the now—questions that carry weighty implications for social futurity.

Nina Peterson (she/her) is a Ph.D. candidate in art history at the University of Minnesota. Currently based in Denver, she researches histories of photography, film, and performance in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

[1] As art historian Rosalind Krausse asserts, the grid “functions to declare the modernity of modern art.” Rosalind Krauss, “Grids,” October 9 (Summer 1979): 51, https://doi.org/10.2307/778321. For a discussion of the grid (or, as the art historian Lynda Nead describes Albrecht Dürer’s use of a drafting tool, “a framed screen which is divided into four sections”) as a tool used to regulate the body and to define it in rigidly binaristic terms of gender, see Lynda Nead, The Female Nude: Art, Obscenity, and Sexuality (Routledge, 1992), 11. For a discussion of the grid and its relationship to data organization and racial capitalism, see Jussi Parikka, Operational Images: From the Visual to the Invisual (University of Minnesota Press, 2023), 49–50. Parikka draws upon Simone Browne’s work. Simone Browne, Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness (Duke University Press, 2015), 47–49.

[2] Ben Tracy, “How the surging demand for energy and rise of AI is straining the power grid in the U.S.” CBS News, July 19, 2024, www.cbsnews.com/news/how-surging-demand-for-energy-and-rise-of-ai-is-straining-the-power-grid-in-u-s/. See also https://www.popularmechanics.com/science/a64929206/singularity-six-months/.

[3] Collin Parson, "Collin Parson," interview by Mary Meng-Frecker. Accessing the Arts: Regis College Fine Arts Interviews with Visiting Artists, January 6, 2017, video, 18:46, https://epublications.regis.edu/artist_interviews/9.

[4] Though further examination exceeds the scope (and word count recommendations) of this review, Parson’s work raises questions about how the aesthetics of the Light and Space movement change in the contemporary moment as well as the relationship between artistic strategies of perceptual re-orientation and the ways in which Big Tech holds immense influence over the structure of contemporary social life (e.g., Meta’s and X’s roles in fueling a crisis in democracy). Artists of the Light and Space movement collaborated with high-tech industries (for instance, Robert Irwin worked with engineers from the aerospace manufacturer the Garrett Company) during the 1960s and ‘70s with aspirations of using art as a tool for the transformation of everyday life. Yet, as scholars including media theorists John Beck and Ryan Bishop have argued, today’s Silicon Valley corporations have easily appropriated the rhetoric of interdisciplinary experimentation deployed by mid-century avant-garde artistic and engineering collaborations, mobilizing this rhetoric towards the exploitative practices that further concentrate wealth and power in the hands of Big Tech. John Beck and Ryan Bishop, Technocrats of the Imagination: Art, Technology, and the Military-Industrial Avant-Garde (Durham: Duke University Press, 2020), 11. For a discussion of Irwin’s collaborations with the Garrett Company, see “Interview with Robert Irwin about the First National Symposium on Habitability of Environments.” Weisman Art Museum, October 1, 2018, https://wam.umn.edu/interview-robert-irwin-about-first-national-symposium-habitability-environments#_ftn3.

[5] Bollmer and Guinness distinguish between two classes of influencer: the first is a precarious worker class that aspires to the economic status of the second, which is tantamount to a capitalist class that controls the means of production and distribution of the self. Grant Bollmer and Katherine Guinness, The Influencer Factory: A Marxist Theory of Corporate Personhood on YouTube (Stanford University Press, 2024), 35-37.

[6] Surrealist Max Ernst used grattage and its analogous rubbing technique frottage as strategies of automatism, or of tapping into the unconscious and revealing surprising or unexpected realities. See Max Ernst, “What is Surrealism?,” in Surrealists on Art, ed. Lucy Lippard (Prentice Hall, 1970), 135, https://monoskop.org/images/9/93/Lippard_Lucy_R_ed_Surrealists_on_Art_1970.pdf.

[7] The term has since gained theoretical elaboration in the work of self-dubbed futurists and tech-entrepreneurs including Ray Kurzweil. Vernor Vinge, “The Coming Technological Singularity: How to Survive in the Post-Human Era,” article for VISION-21 Symposium, sponsored by NASA Lewis Research Center and the Ohio Aerospace Institute, March 30-31, 1993. Available at https://edoras.sdsu.edu/~vinge/misc/singularity.html.