Mutations | How Soon We Forget

Dr. George Rivera: Mutations

Christopher Meyer: How Soon We Forget

fooLPRoof Contemporary Art

3240 Larimer Street, Denver, CO 80205

September 5–December 27, 2025

Admission: Free

Review by Parker Yamasaki

You could call Dr. George Rivera a painter. You could also call him a curator and critic. You could call him a world traveler, an art collective founder, and a children's book author. A Mexican American, a cancer survivor, a Fulbright scholar, a professor, and an explorer.

An installation view of George Rivera’s exhibition Mutations and Christopher Meyer’s exhibition How Soon We Forget at fooLPRoof Contemporary Art. Image by Laura Phelps Rogers.

It's all there in the exhibition Mutations at fooLPRoof Contemporary Art, even if you can't immediately see it. Or even see it at all.

This body of work, mounted and hung for the first time, is the work of Rivera's subconscious—an accumulation of life channeled through ink blot paintings based on his experiences with the Uitoto Tribe in South America.

George Rivera, Untitled, 2025, composite image of ink drawings printed on fabric, 62 x 84 inches. Image by Laura Phelps Rogers.

Inspired by the tribe's use of plant dyes, Rivera worked with a shaman to create a set of inks out of plants found in the Amazon: Achiote reds, Azafran (saffron) yellows, and browns made of cacao seeds.

That the natural tones were made from picking, plucking, uprooting, and crushing Earth's bounty speaks to one of the reasons for Rivera's Amazon trip in the first place: to witness and understand the destruction of the rainforest.

George Rivera, a series of Untitled drawings, 2023, ink on paper mounted on canvas panels with barnwood top mount, 62 x 64 inches. Image by Parker Yamasaki.

Since the 1980s cries of "Save the Rainforest" have reverberated from the interior of Brazil, which holds about half of the Amazon basin, and crossed the lips of U.S. politicians, celebrities, artists, and advocates. Rivera's work is less a cry for help as it is deep introspection about what it means to destroy the most biodiverse region on the planet.

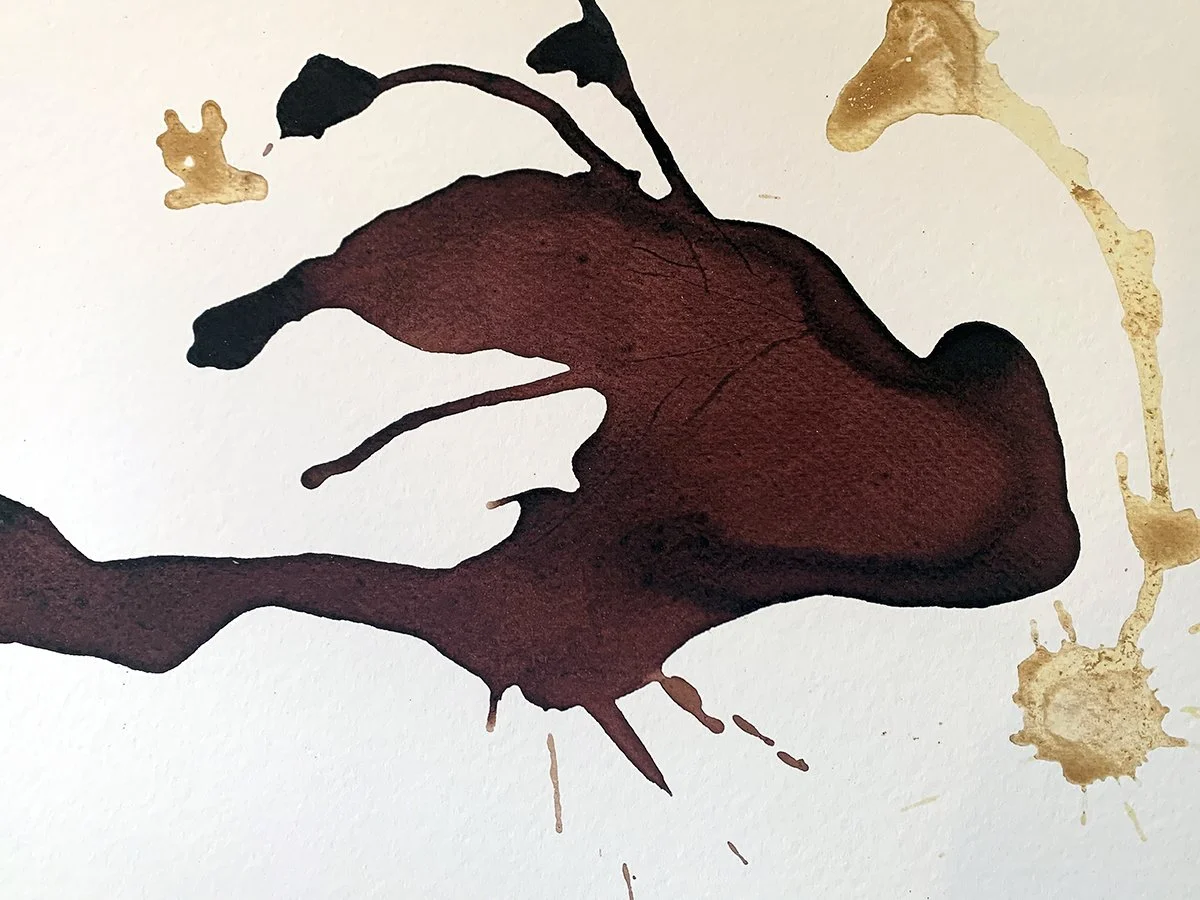

A detail view of George Rivera’s Untitled drawing, 2025, fine art print of ink drawing mounted on Dibond, 23 x 29 inches each. Image by Parker Yamasaki.

That introspection, it's messy.

Too messy to frame and hang on a gallery wall, even, though gallery manager and curator Laura Phelps Rogers has tried her damn best.

The title wall for George Rivera’s exhibition Mutations and Christopher Meyer’s exhibition How Soon We Forget at fooLPRoof Contemporary Art. On the left: George Rivera, a series of Untitled drawings, 2023-2024, ink on paper mounted on wood panels, 11 x 14 inches each. In the center: Christopher Meyer, Tall Green Ash, 2014-2024, performance-based cast iron, 24 x 16 inches. On the right: George Rivera, Untitled, 2023, ink on cotton rag paper, 29 x 24 inches. Image by Parker Yamasaki.

Rogers has wrangled a set of fifteen letter-sized paintings onto wooden mounts and arranged them into a three-by-five grid. Another group of sixteen works are chained together with thin wires and hung quilt-like from a wooden beam.

The works in these sets feel rapid. Rivera works each piece in only one or two colors, gently guiding the inks into animalistic forms with an occasional limb or wing protruding from a core of color. The intensity of the paintings seems drawn from tapping into the subconscious (don't overthink it) and interfacing with non-human animals, exemplifying what we might call "animal instinct."

George Rivera, Untitled drawings, 2025, fine art prints of ink drawings mounted on Dibond, 23 x 29 inches each. Image by Parker Yamasaki.

A detail view of George Rivera’s Untitled drawing, 2025, fine art print of ink drawing mounted on Dibond, 23 x 29 inches each. Image by Parker Yamasaki.

In order to mount the larger prints, Rogers had prints made on thick paper with deckled edges, which hang at the front of the gallery. From the center of the room the prints are indistinguishable from the originals, aside from the fact that they are flat enough to be framed. Up close, the printed pools of ink create an uncanny, two-dimensional effect that clues the viewer into the digital processing.

A detail view of one of George Rivera’s Untitled drawings, 2023, ink on linen mounted to canvas, 24 x 24 inches. Image by Parker Yamasaki.

One work has been printed onto a square canvas and in the places where two or three colors overlap, the inks are drawn into the texture of paper that no longer forms its base. This disappearance of the raw material is fitting for a show that remarks on the ways humans intervene and mold the earth to suit our desires.

George Rivera, Untitled drawing, 2023, ink on paper, 27 x 30 inches. Image by Parker Yamasaki.

George Rivera, Untitled drawing (detail), 2023, ink on paper, 27 x 30 inches. Image by Parker Yamasaki.

In contrast, eight original paintings, unframed and pinned to the wall near the back of the gallery, are as warped and wobbly as a kindergartener’s watercolors on printer paper. These pieces offer a completely different experience than the smoothed out works built and framed to sell. The unframed works are textured and in some areas, Rivera applies the ink so heavily that the paper has started to pill.

It's here that the viewer can feel the sincerity of Rivera's works—his complete dedication to the material and moment, likely without foresight about where they'll end up or if they will sell.

Three works by Christopher Meyer, from left to right: Scotch Pine, 2014-2024, performance-based cast iron, 20 x 18 inches; Root Bound, 2014-2024, performance-based cast iron, 14 x 14 inches; Buckthorn Small, 2014-2024, performance-based cast iron, 10 x 11 inches. Image by Parker Yamasaki.

Standing among the paintings are the cast iron sculptures of Christopher Meyer in the exhibition How Soon We Forget. Meyer creates these works by pouring iron into a reactive mold—here, the molds are hollowed out tree logs—creating an eruption of fire and flares. When the show is over, what's left behind is the coarse, patinated shell of a stump.

A photo of Christopher Meyer creating cast iron works in his Shelterbelt series. Image courtesy of the artist.

"At the time of Lewis and Clark, setting the prairies on fire was a well-known signal that meant, 'Come down to the water.' It was an extravagant gesture, but we can't do less," Annie Dillard wrote in her Pulitzer Prize-winning book, Pilgrim at Tinker Creek. "If the landscape reveals one certainty, it is that the extravagant gesture is the very stuff of creation. "

Christopher Meyer, Phallus, 2014-2024, performance-based cast iron, 17 x 20 inches Image by Parker Yamasaki.

Meyer, who is based in South Dakota, has watched as groves of trees and shelter belts—the rows of trees planted in the Plains region as windbreaks and to prevent soil erosion—disappear around him, ripped up to make room for more planting in an ever-expanding agricultural patchwork. He began the tree castings in 2014 with the intention of forming his own shelter belt.

Three works by Christopher Meyer, from left to right: Green Ash, 2014-2024, performance-based cast iron, 11 x 24 inches; Green Ash Small, 2014-2024, medium performance-based cast iron, 15 x 9 inches; Hackberry, 2014-2024, performance-based cast iron, 20 x 20 inches. Image by Parker Yamasaki.

By the time the sculptures make it to the gallery floor, the performance, too, exists only in memory. The shorn, crisp frames stand as relics—a moment in the cycle of human-caused destruction and creation, stunted in iron.

A detail view of Christopher Meyer’s Scotch Pine, 2014-2024, performance-based cast iron, 20 x 18 inches. Image by Parker Yamasaki.

As the rest of the Dillard quote goes: "The whole show has been on fire from the word go. I come down to the water to cool my eyes. But everywhere I look I see fire; that which isn't flint is tinder, and the whole world sparks and flames."

Rogers recently acquired a former nightclub next door to fooLPRoof. In mid-October she was working through the heat of that expansion, passing back and forth between the two spaces, trying to coordinate the arrival of the next show — a solo show by Sahand Tabatabai—while accounting for the dozens of paintings that Rivera left with her.

Laura Phelps Rogers, the gallery manager and curator of fooLPRoof Contemporary Art, opens a box of George Rivera’s Untitled drawings, 2023, ink on paper, 11 x 15 inches each, from the backstock of his Mutations collection. Image by Parker Yamasaki.

The closing date for Mutations and How Soon We Forget may be pushed back by a week to allow a gasp of breath between the shows and the move. Some of the work will move into the bar-slash-gallery next door and some will line the hallway passage between the two spaces. Then there is the drawer full of boxes, crammed with even more of Rivera's paintings she hadn't hung. The sculptures might remain in place, they might not. Rogers wasn't sure at that moment. Maybe she'd rearrange them into a circle at the center of the room, she thought aloud, then quickly abandoned the idea.

In the foreground, two works by Christopher Meyer. On the left: Twisted Ash, 2014-2024, performance-based cast iron, 16 x 20 inches, and on the right: Cottonwood, 2014-2024, performance-based cast iron, 10 x 14 inches. In the background: George Rivera, Untitled, 2025, composite giclée print on fabric of ink drawing, 62 x 84 inches. Image by Parker Yamasaki.

The point is: the show may or may not be up when you read this. It may have moved next door, been rearranged or redistributed. The more enduring point is: try to catch it before it's gone.

Parker Yamasaki (she/her) is a western states arts writer based in Lafayette, Colorado. She is a culture reporter for the statewide, nonprofit newsroom The Colorado Sun. She is also a freelance critic. Her work has been published in The Chicago Reader, Newcity Chicago, Austin Monthly, and various online publications.