In Other Words / Word Play

Roland Bernier: In Other Words

Word Play

Arvada Center for the Arts and Humanities

6901 Wadsworth Boulevard, Arvada, CO 80003

September 17-November 14, 2021

Curated by Emily King and Collin Parson

Admission: Free

Review by Eric G. Nord

U.S. art history is rife with artists who explore and exploit text in their practices. From Barbara Kruger to Bruce Nauman, Jenny Holzer to Ed Ruscha, and Cy Twombly to Christopher Wool, artists have utilized text to imbue their work with wit, imply deeper significance, insert subtle satire, or provide a literary context to the imagery. Including text in visual art can be a tricky undertaking though, as it can often prescribe a particular meaning, narrowing the viewer’s interpretation and fixing it to a specific understanding. In contrast, in the artworks of the late Roland Bernier—featured in one of two recently-premiered, text-based exhibitions at The Arvada Center for the Arts—the meaning of words and linear narratives retreat and recede. The visual aesthetic of the text takes precedence, disassociating it from its practical purpose where words serve as metaphor.

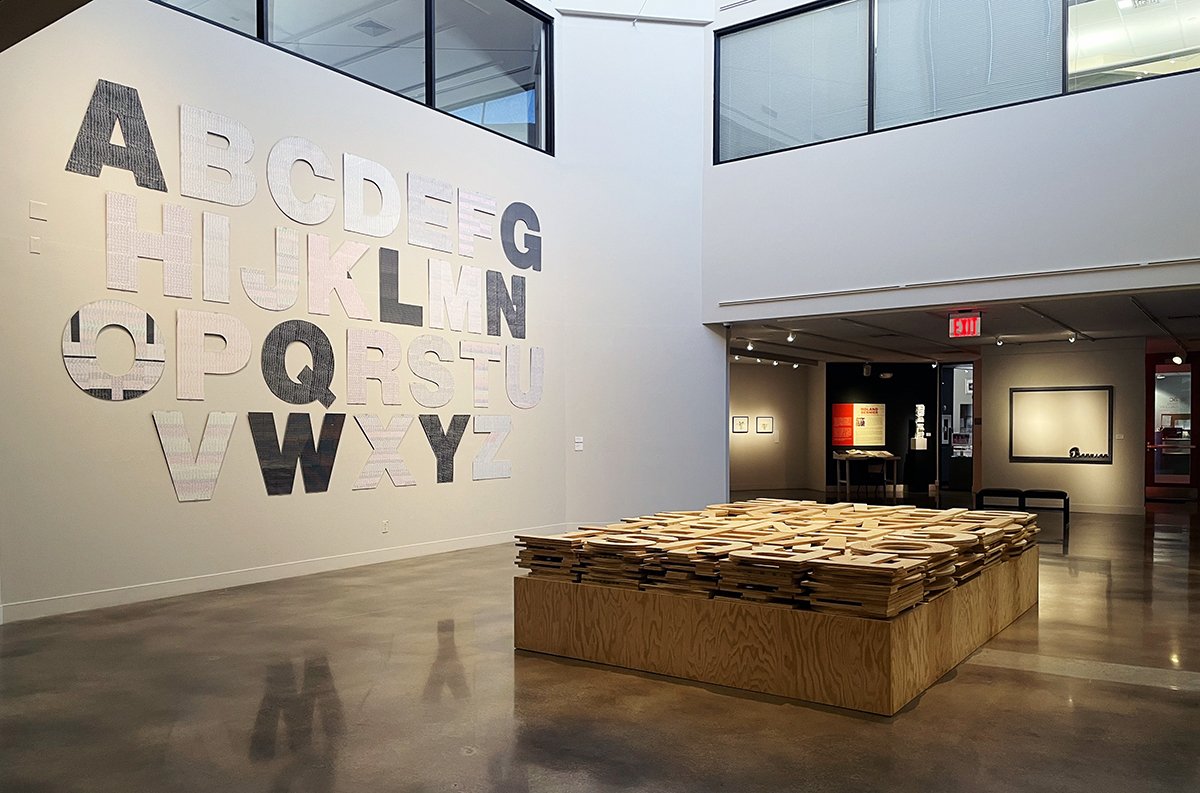

A view of works in the exhibition Roland Bernier: In Other Words on display at the Arvada Center for the Arts and Humanities. Image by DARIA.

Roland Bernier was an important figure in the Denver art community, both as artist and advocate, for over forty years. He took up residence here with his wife Marilyn in the early 1970s. In 2001, his work was featured in a solo exhibition at the Denver Art Museum. Walker Fine Art, which continues to represent his work posthumously, mounted a major retrospective in 2007. And his monumental piece Wall of Words was installed at the Denver Convention Center in 2014, shortly before his death in 2015 at age 83.

Roland Bernier, Word Works, 2000, plywood, 12 x 8 x 3 feet. Image by DARIA.

Although Bernier’s early artistic output was solidly within the genre of Abstract Expressionism, while living in NYC in the late 1960s he began incorporating text, possibly as a result of the increasing influence of Pop Art. However, his predilection for eschewing or obfuscating the meaning of words seems to have been a continuation of his AbEx background—detaching artwork from the obsolete symbolism of earlier artistic movements.

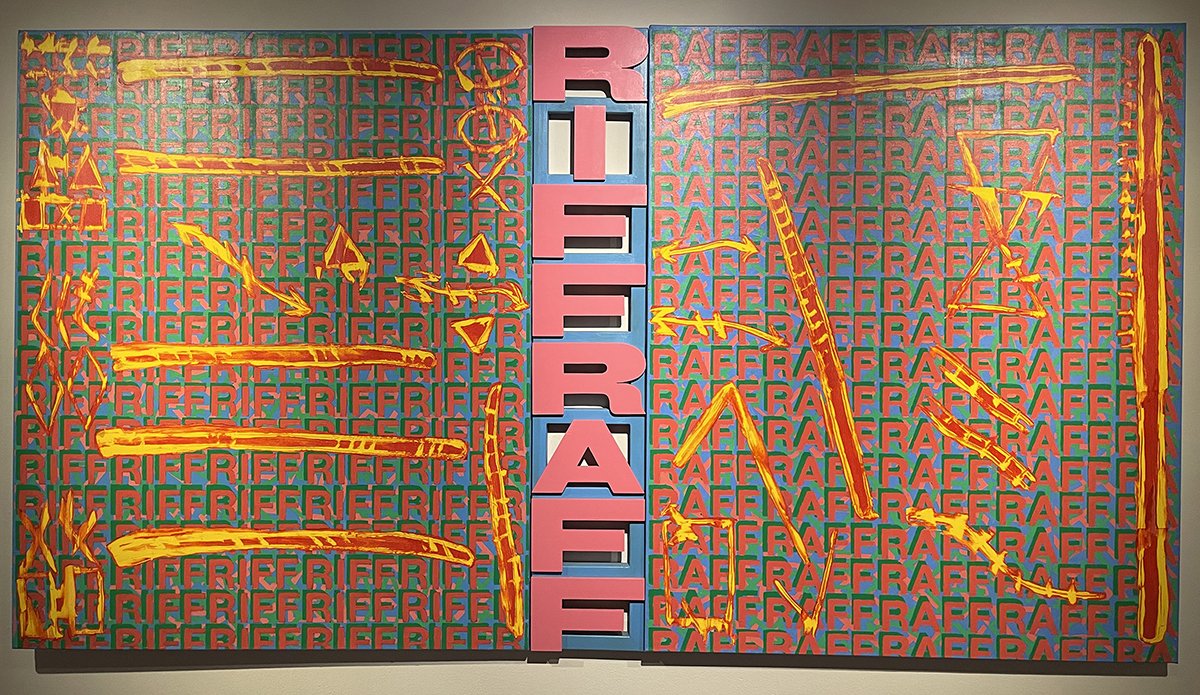

Roland Bernier, RiffRaff, 1993, acrylic on canvas, 60 x 111 inches. Image by DARIA.

An example of this approach is Bernier’s monumental Word Works from 2000. Prominently featured in the central exhibition hall in the Arvada Center, this three-dimensional piece is made of plywood, has a footprint of twelve feet by ten feet, and stands three feet tall. The work looms so large that any attempt to discern the words seems inconsequential due to its overwhelming physical presence within the space. Two colorful acrylic works on canvas, True Blue (1992) and RiffRaff (1993), feature the addition of enigmatic symbols that allude to a primitive or aboriginal source. Yet, much like the randomness of the artist’s word choices, what they represent takes a subordinate role to how they impact the overall composition.

The works included in this exhibition—thoughtfully curated by Emily King and Collin Parson with the assistance of the artist’s widow Marilyn Bernier—offer visitors the opportunity to witness the artist’s rigorous exploration of concise and controlled concepts. The restrictive parameters Bernier imposed upon his practice could have easily depleted the well of inspiration of any other artist within a year or two. In his capable hands, the work maintained continuity while evolving with the graduated consistency of a minimalist music composition. The collection spans several decades of artistic production, with the exception of nine years during which the artist took a hiatus from creating, and includes work across the spectrums of scale, dimensionality, materiality, texture, and color.

A view of the group exhibition Word Play at the Arvada Center for the Arts and Humanities. In the center, two works by Joel Swanson: Webster’s Dictionary, found dictionary illustrations and digital animation, 2021, and NO/NOT/NOTHING, powder-coated aluminum and cable, 2021 . Image by DARIA.

The accompanying exhibition, Word Play, is comprised of works from 15 additional contemporary Colorado artists. It demonstrates the great expanse of possibilities within text-based art, while further emphasizing the conscious restraint that Bernier employed. The variety of artistic approaches presented, both materially and conceptually, resonate well with Bernier. One marked difference in Word Play is a greater emphasis on meaning and its use in conveying the intent of the artists. At times, these artists are more aligned with the work of those behemoths I referenced at the introduction of this article than with Bernier’s more concrete approach.

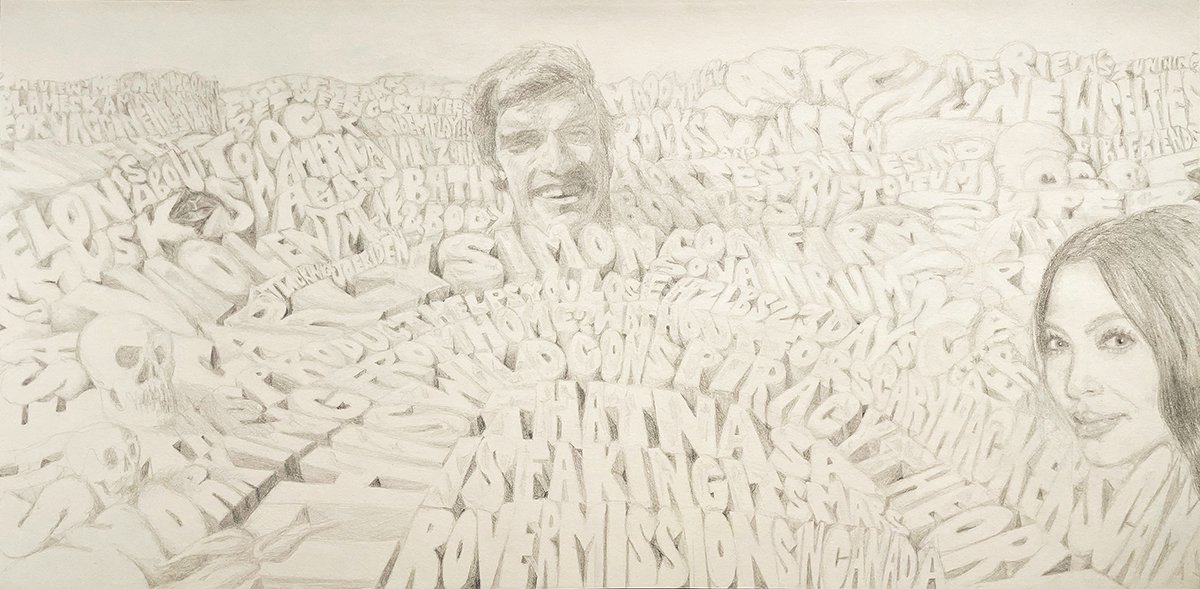

Donald Fodness, Landscape 2021 with Icons, 2021, graphite on paper. Image by DARIA.

There are two exceptions to this observation. Don Fodness’ Landscape series, in which he compressed recent newspaper headlines into rolling hills of balloon text, impeding the ability to intuit the content yet implying a critique of the absurdity and meaninglessness of our incessant news cycle. And Tom Mazzullo’s silver point pieces Improvisations On Type, which although not technically words, invoke words in their representations of the individual letter blocks once used in typesetting.

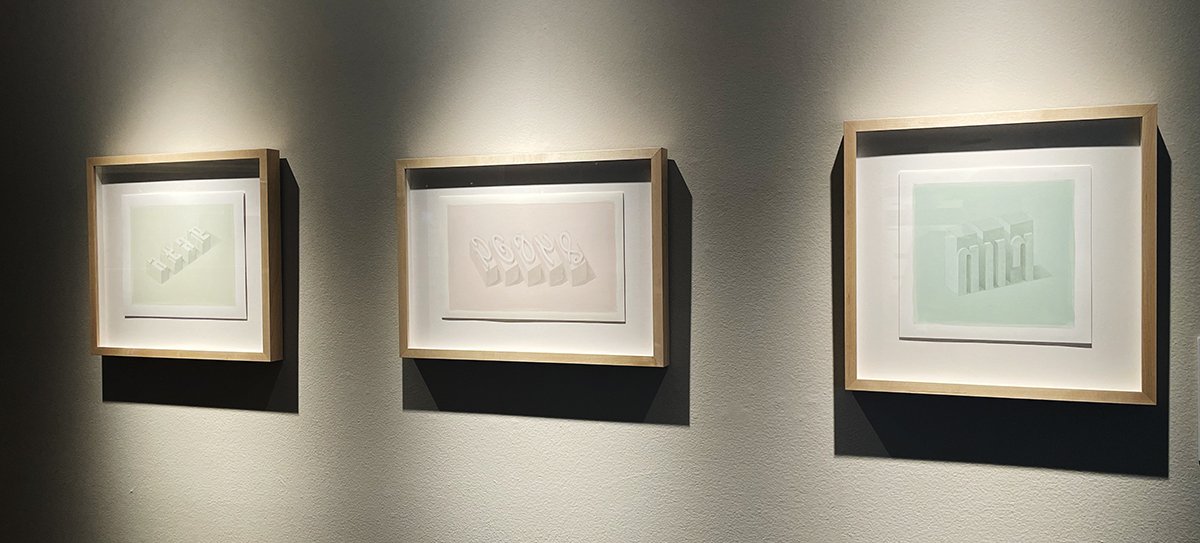

Tom Mazzullo, from left to right: Type Improvisation on y, silverpoint with white gouache on casein-prepared paper, 2019; Type Improvisation on G, silverpoint with white gouache on casein-prepared paper, 2017; and Type Improvisation on n, silverpoint with white gouache on casein-prepared paper, 2017. Image by DARIA.

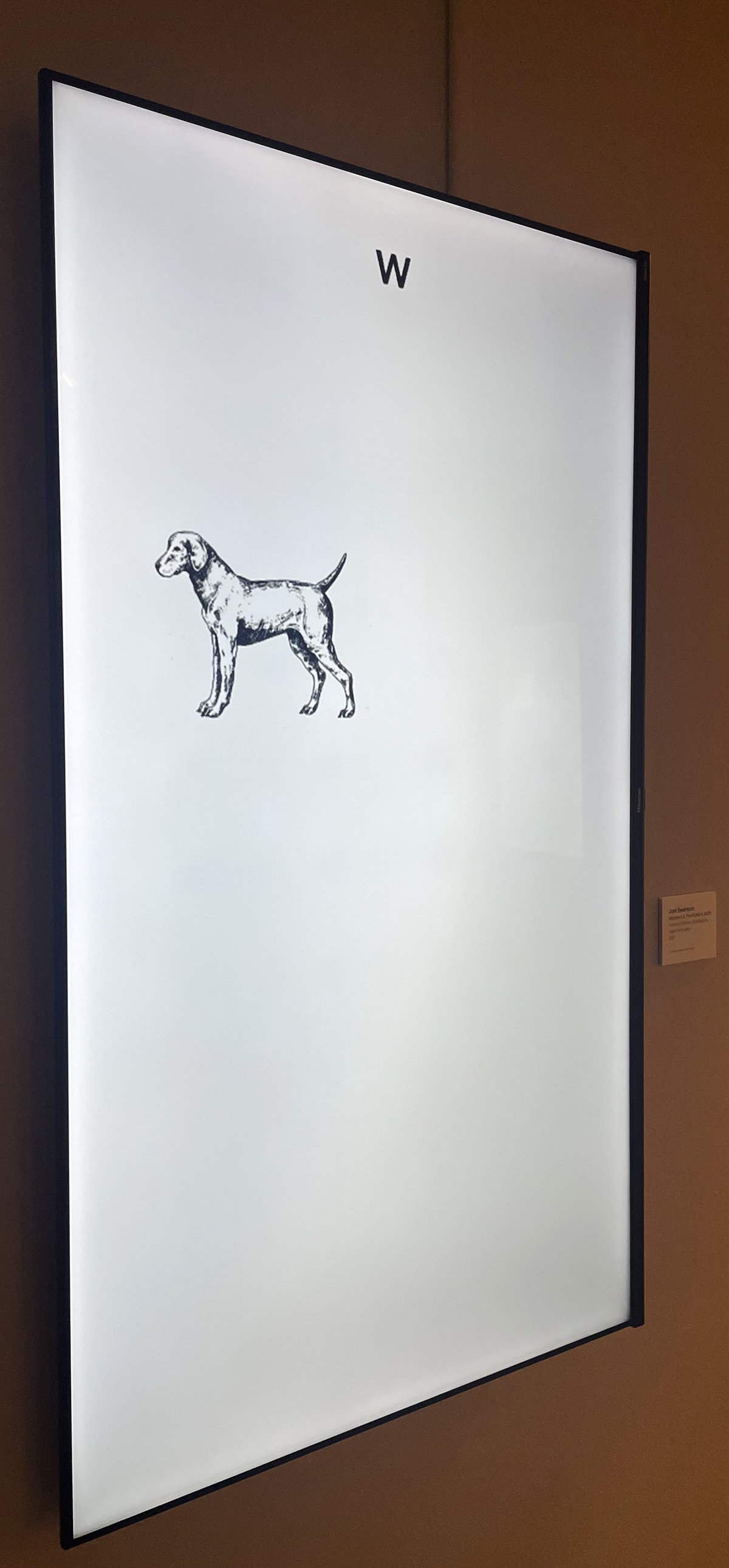

The use of words throughout Word Play is not confined to English, which could also obscure meaning depending on one’s familiarity with foreign languages. These include works by Lares Feliciano in Spanish, Paula Gasparini-Santos in Portuguese, Sammy Seung-Min Lee in Korean, and Masha Sha in Russian. Four video pieces by Joel Swanson eliminate the visual appearance of words altogether, and instead show illustrations from various dictionaries used to accompany the definition of words, prompting the viewer to conceptualize the associated words in their own minds. Other works employ devices often utilized in text-based pieces, including redaction in Paul Weiner’s work, a list of instructions in Trey Duval’s Repeat That Again, and the ubiquitous neon lettering of Scott Young.

A single image on one video screen in Joel Swanson’s Webster’s Dictionary, found dictionary illustrations and digital animation, 2021. Image by DARIA.

As a complete experience, the two exhibitions offer a wide variety of interesting approaches to the use of text in art. They support each other visually, while adding depth and diversity conceptually. The wide range of viewpoints and applications of text in Word Play add weight and breadth to the focused constraint of Roland Bernier: In Other Words. And the proliferation of meaning apparent in some works galvanizes the absence of overt meaning in others. You have until November 14th to view these two worthwhile exhibitions. However, you must make an appointment on their website, and wearing a mask is required.

Eric Nord received a degree in Art History from the University of Denver. Previously, he served as Executive Director of the E. E. Cummings Centennial Celebration in New York City, worked for Sperone Westwater Gallery in NYC, and is currently the Director of Leon Nonprofit Arts Organization in Denver.