In Between

In Between

Downtown Aurora Visual Arts (DAVA)

1401 Florence Street, Aurora, CO 80010

March 18-April 22, 2022

Admission: Free

Review by Ashten Scheller

Walking into the Downtown Aurora Visual Arts (DAVA) center on a sunny afternoon, it’s difficult not to notice the community energy the area exudes. The downtown neighborhood is colorful and visually engaging, with vibrant buildings and kaleidoscopic street art around every corner. It’s late afternoon and I’ve accidentally entered through the wrong door—the one by the classroom spaces, near the back. But I’m greeted warmly by one of the high school students currently working on a project, before being introduced to director Krista Robinson. She leads me into the gallery space, the true destination of my visit to Aurora today. I’m immediately struck by the bright gallery space with natural light streaming in from the skylight above.

An installation view of the group printmaking exhibition In Between on view at the Downtown Aurora Visual Arts (DAVA). Image by Ashten Scheller.

I’m introduced to curator Viviane Le Courtois, who has put together the current show: In Between, a printmaking exhibition. It’s part of the Month of Printmaking (or Mo’Print, for short), and Le Courtois has curated an exhibition showcasing local Colorado artists from various backgrounds. Each artist is in some way “in between” two or more identities: gender, culture, language, religion, place, nationality, ability, or ethnicity.

The artists not only examine and describe their own identity (or identities), but also question the validity of having to belong to one group over another. Cleverly, Le Courtois has included artist autobiographies, allowing each individual to fully describe and claim their own groups of belonging. Each text facilitates a deeper connection with the artist—a sensitive and welcoming approach for the personal, central topic of identity.

Jon Olson, Glove, monoprint. Image by DARIA.

Jon Olson’s installation is perhaps the most immediately arresting you encounter. It hangs from the ceiling supports in the middle of the gallery space and is comprised of eight separate prints, each depicting a monoprint of a distinct glove. In his process of using found objects from the streets and inking them to make prints, Olson represents various identities of the working class: each glove corresponds to a different occupation, ever-present in our environment but often discarded and forgotten, out of the public eye.

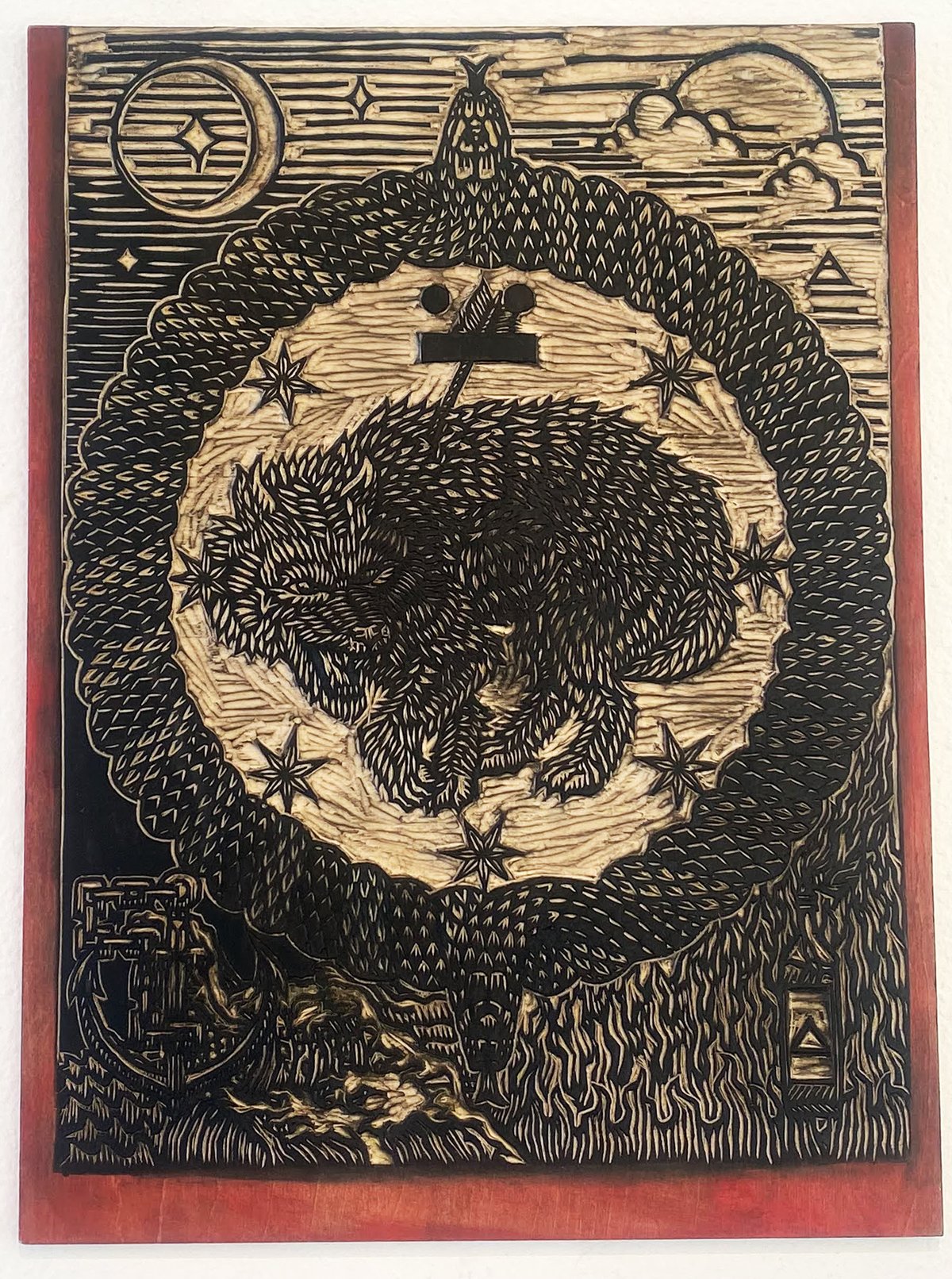

Javier Flores, Woodblock for Reverence, 2018. Image by Ashten Scheller.

In front of Olson’s hanging prints stands a white plinth with a carved woodblock by Javier Flores. Born in Denver and the son of Mexican immigrants, Flores was raised in a blue-collar household, which he openly credits for producing his strong work ethic, honesty, and integrity. At the age of nineteen, he was shot in the lower back and was subsequently paralyzed. This life-changing event led to shock, depression, and suicidal ideation, but he was “saved by family, friends, visual arts and martial arts.” He now teaches at Front Range Community College in addition to having affiliations with Access Gallery and Museo de las Americas.

His woodblock on view depicts an open-mouthed, growling wolf surrounded by a circular, curling snake, an anchor, and natural elements such as the moon and sun. In this piece, the wolf has become a familiar for himself, “roaring in frustration at the dichotomy of being raised in the U.S. but holding onto the culture and heritage of being from Mexican descent and the subjugation of that population through Capitalism and Colonialism.” [1] The detail and care in Flores’ printmaking process are evident due to the inclusion of this original woodblock in addition to his other final pieces hanging on the wall nearby. It prompts the viewer to imagine the hours of carving necessary to create a single print.

Jordyne Salinas, La Virgen, 2021, linoleum relief carving. Image by Ashten Scheller.

Across the space, Metropolitan State University student Jordyne Salinas has contributed their linoleum relief carving La Virgen (2021). This is a bold graphic print depicting Miss Piggy in the place of a traditional Lady of Guadalupe image, Kermit the Frog replacing the traditional winged cherubic angel upon which the woman stands, and the prominent colors of the Mexican flag (green, white, and red) in large swathes in the background. Originally from Houston, Texas, Salinas finds inspiration in their personal experiences growing up in a Chicano family.

La Virgen was inspired by both American media consumption and Mexican spiritualism—both key parts of Salinas’ identity. [2] Miss Piggy and Our Lady of Guadalupe are prominent childhood figures for Salinas, but represent vastly different expressions of womanhood. Their combination reflects the artist’s upbringing as a third-generation Mexican-American.

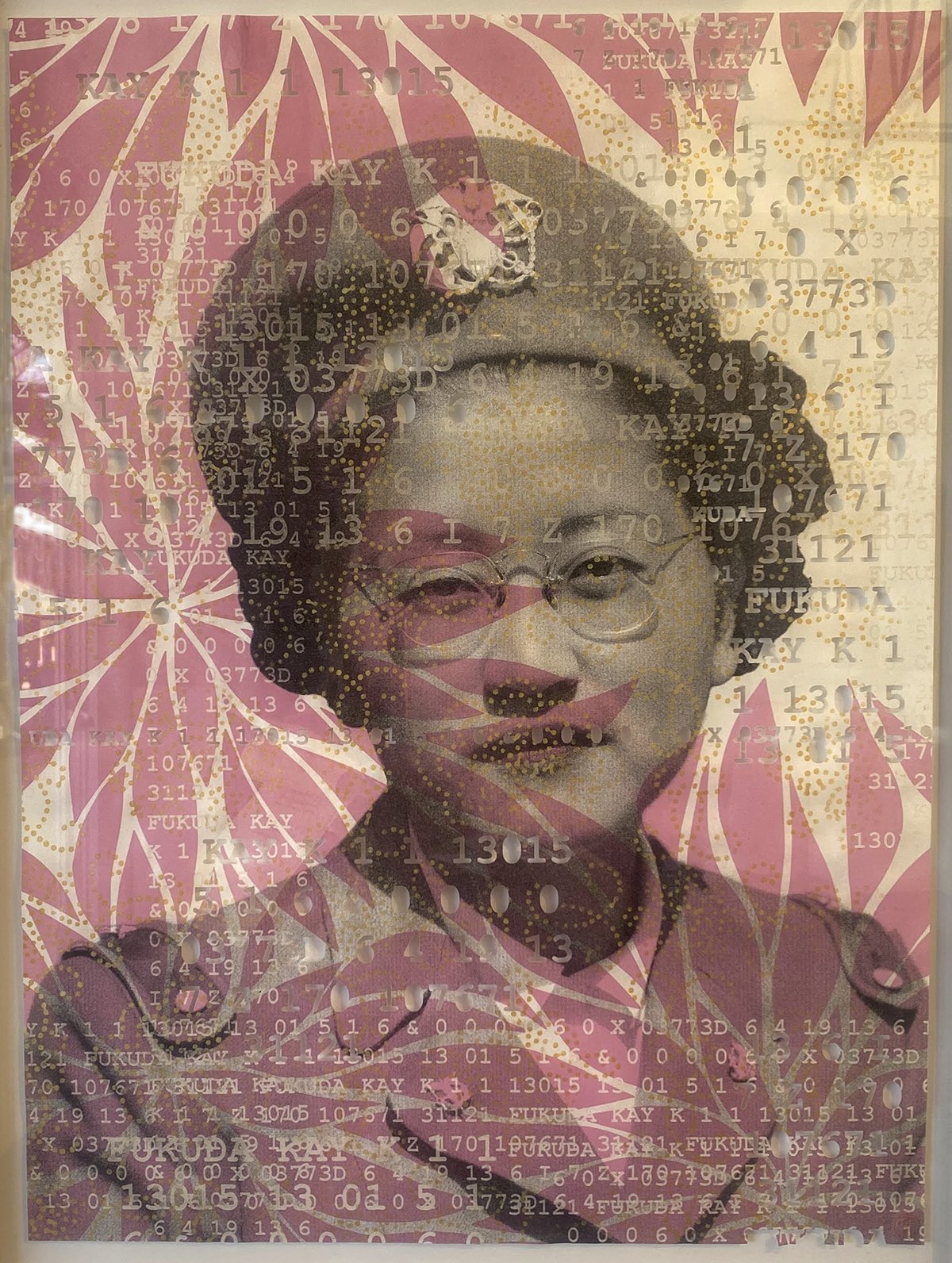

Sarah Fukami, 03773D (Fukuda Kay) II, 2017, photo plate lithography, screen printing, and laser cutting on paper, 18 x 24 inches. Image by Ashten Scheller.

Two prints by Sarah Fukami also connect with a background rooted in immigration. But these works directly reclaim a violently forced loss of identity: that which happened due to the Japanese internment camps created by the U. S. during World War II. Fukami was born and works in Denver, specializing in mixed-media printmaking with a particular emphasis on the immigrant experience. Her own Japanese-American family was interned during WWII, and her art maintains a personal rootedness in social justice.

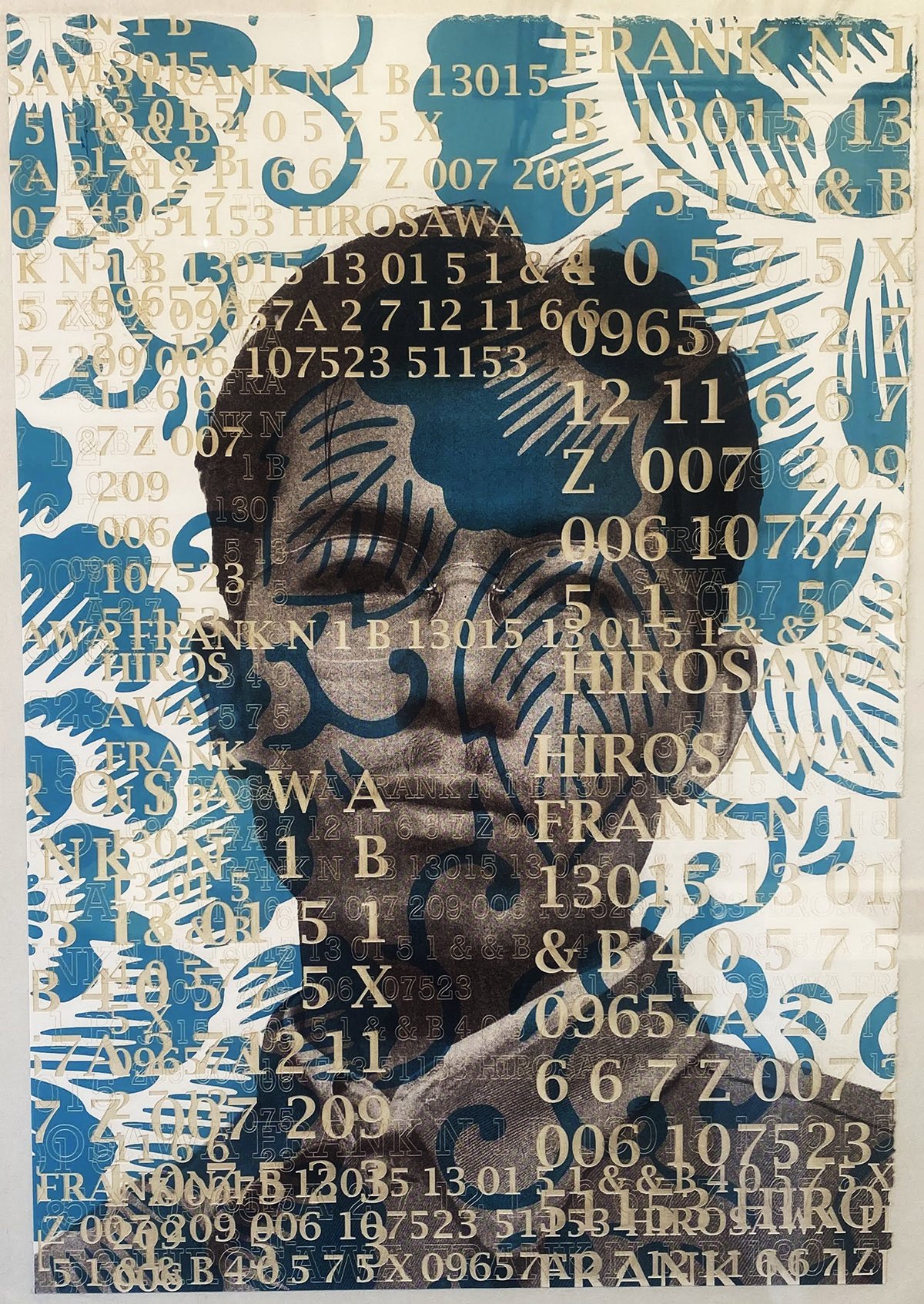

Sarah Fukami, 09657A (Hirosawa Frank) IV, 2017, photo plate lithography, screen printing, and laser cutting on paper, 15 x 21 inches. Image by Ashten Scheller.

The two prints on display, 03773D (Fukuda Kay) II (2017) and 09657A (Hirosawa Frank) IV (2017), focus on original portraits by the photographer Ansel Adams of individuals who were interned at the Manzanar concentration camp in California. The images were commissioned by the War Relocation Authority, who oversaw the internment. Using the National Archives, Fukami identified these people, who were otherwise represented only by letters and numbers—their humanity reduced to numerical data.

Here, Fukami restores the identities, but has physically distorted the images with laser-burned overlays of the numerical data representing the erasure and damage caused by the dehumanizing ideology at the root of the internment camps themselves. The portraits directly engage the viewer and are no longer only data or objects in this process. The colorful elements, in contrast, replicate and celebrate traditional Japanese patterns and printmaking styles. Despite the pain and loss in this history, there is still joy.

Zachary Carlisle Davidson, Am I not a Brother & a Man?, 2015, screen print. Image by Ashten Scheller.

Zachary Carlisle Davidson addresses his multiracial identity through a similar process of recognizing and confronting the violent systems in which we all exist, especially as citizens of the U. S. Growing up, Davidson experienced the outside world as a “dominant and evangelical white culture” that was “void of sensitivity and critical discourse,” going as far as being “openly violent and vocal against [this sensitivity].” [3] For him, the process of color registration that occurs during printmaking creates layers of richness “under and contributing to the image, especially when its message is uncomfortable.” [4]

His pieces Hi-Yellow Alert (2018) and Am I not a Brother & a Man? (2015) address racial injustice, surveillance, violence, and isolation. His visual style is graphic and engaging, full of pent-up energy as though a major event is just on the brink of occurring. In Hi-Yellow Alert, pop culture (embodied by the wall poster) is combined with elements of death and violence—white figures on the TV stand in contrast with the skull and memento mori creature below. An angry police car and a text message saying “Look B-hind u!” convey a potential threat. Are the shapes on the main figure’s collared shirt religious crosses? Or the “X” of a target? There is a nuance here that asks bold questions.

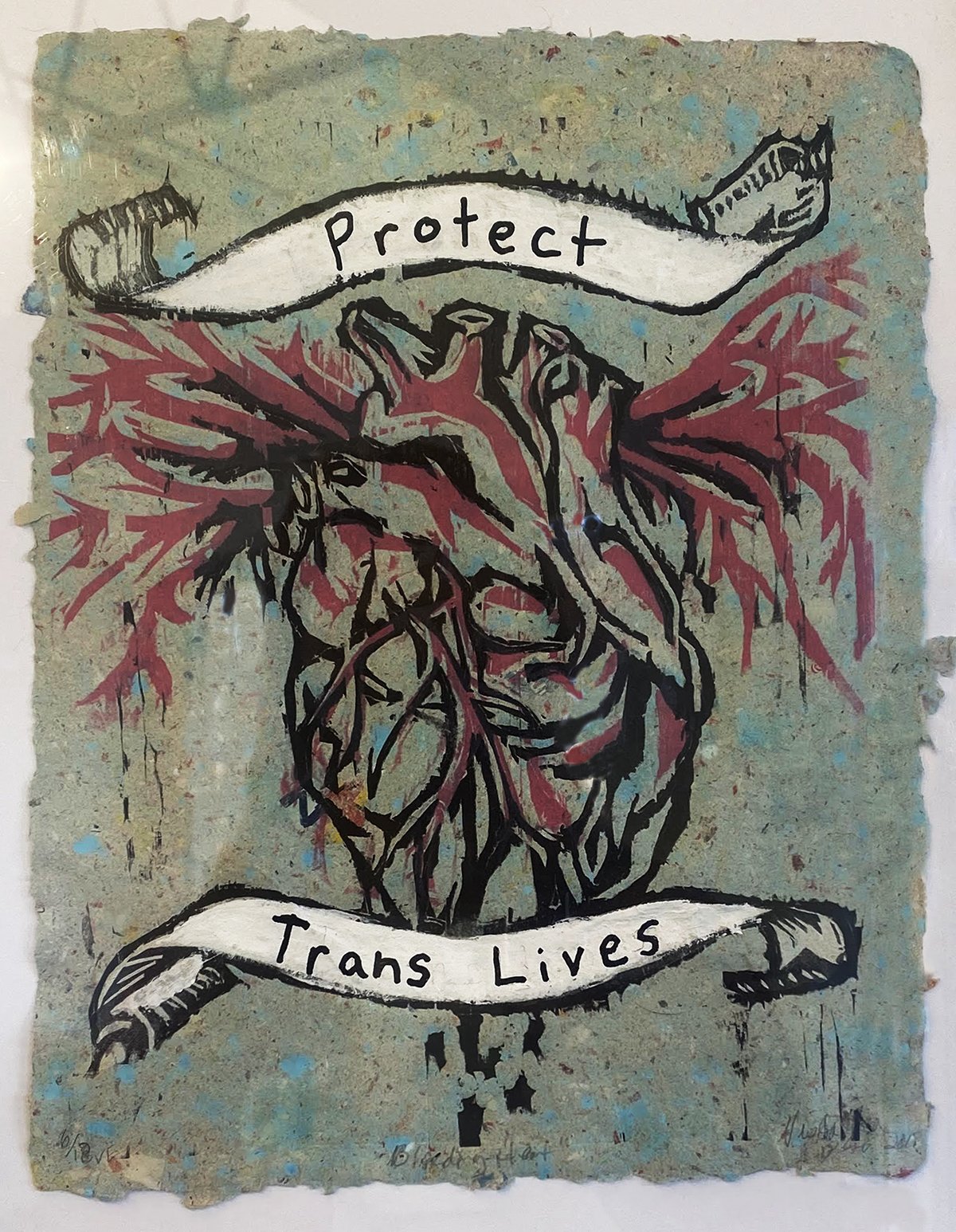

Nitasha Perez, Bleeding Heart: Protect Trans Lives, 2019, woodblock, paint, and paint marker on handmade paper. Image by Ashten Scheller.

Nitasha Perez’s piece Bleeding Heart: Protect Trans Lives (2019) also directly addresses the violence against specific communities and identities—in this case, the Trans community, which continues to experience systemic and legislative violence across the country and around the world. Perez self-identifies as Latinx, Queer, Jewish, and on the Autism Spectrum, and states that “my life is lived from the margins and my artwork reflects that.” [5] The message here leaves little room for ambiguity, with “Protect Trans Lives” printed directly above and below the image of a bleeding heart.

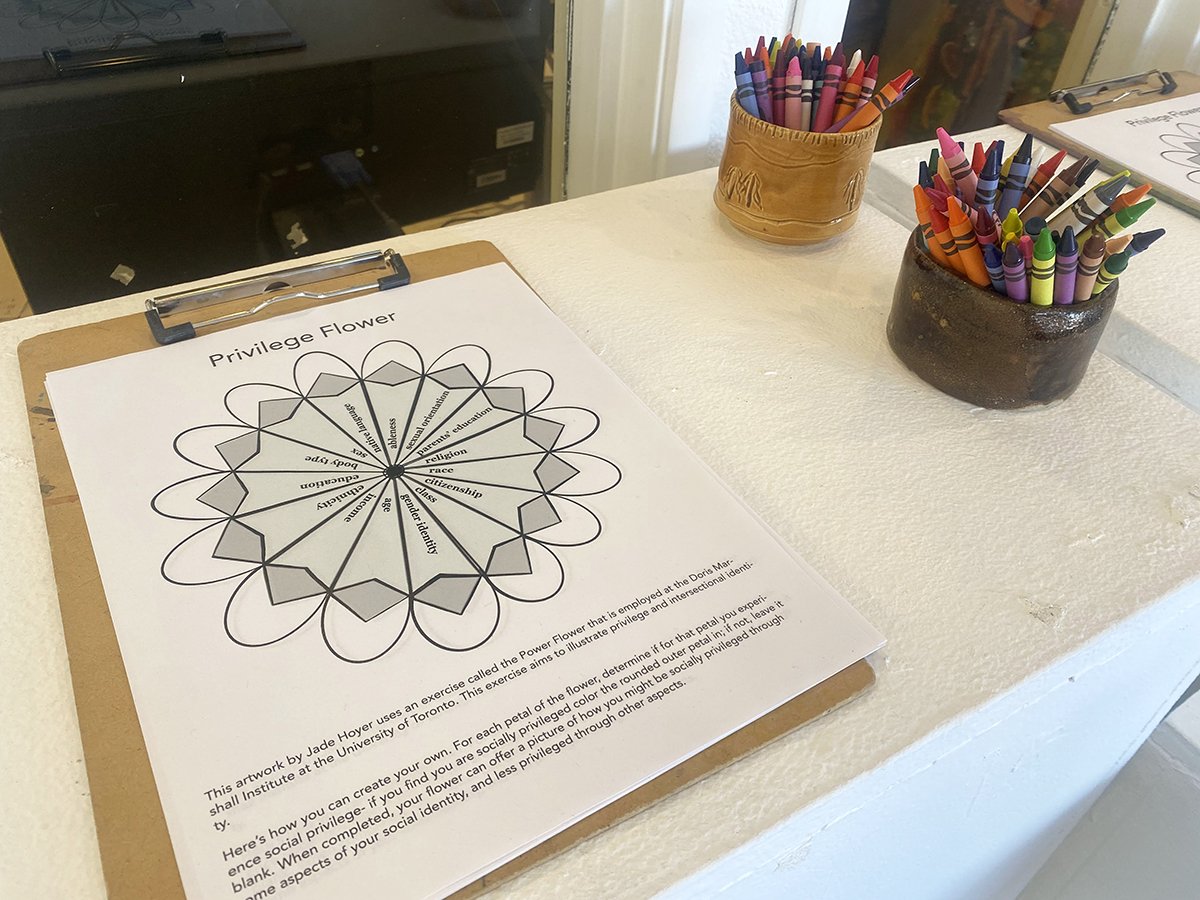

Jade Hoyer, Privilege Flower, 2022, relief monoprint, silkscreen, Scantron forms, colored pencil, and beeswax. Image by DARIA.

Thinking of identity in terms of privilege, Jade Hoyer’s Privilege Flower (2022) is a larger sculptural interpretation of an exercise used at the Doris Marshall Institute at the University of Toronto. Each petal is labeled with a social privilege, with darker outer petals representing greater privilege and lighter, inner petals representing less or nonexistent privilege. The work is stunning, with the inner petals constructed using Scantron test sheets and the outer blue petals made with relief monoprints displaying varied textures.

Jade Hoyer’s Privilege Flower worksheets available for visitors to complete themselves. Image by Ashten Scheller.

Such Scantron test sheets are widely used in the American education system, not only for individual classes and tests, but for widely-distributed standardized tests at the state and even federal level. In using them as her material, Hoyer is possibly alluding to the systemically disproportionate privilege afforded to some students taking standardized tests, such as the college admittance ACT and SAT tests. [6]

For many of these tests, personal identifying questions are often asked at the beginning—including questions about race, ethnicity, or parents’ education—and questions that not every student can answer by simply checking a box. This piece is also interactive, as nearby there is an available printout and cups of crayons for visitors to fill in their own personal copy of the Privilege Flower. The worksheet can then leave the gallery as a tangible reminder of the various forms of privilege with which we are conditioned and interact on a daily basis.

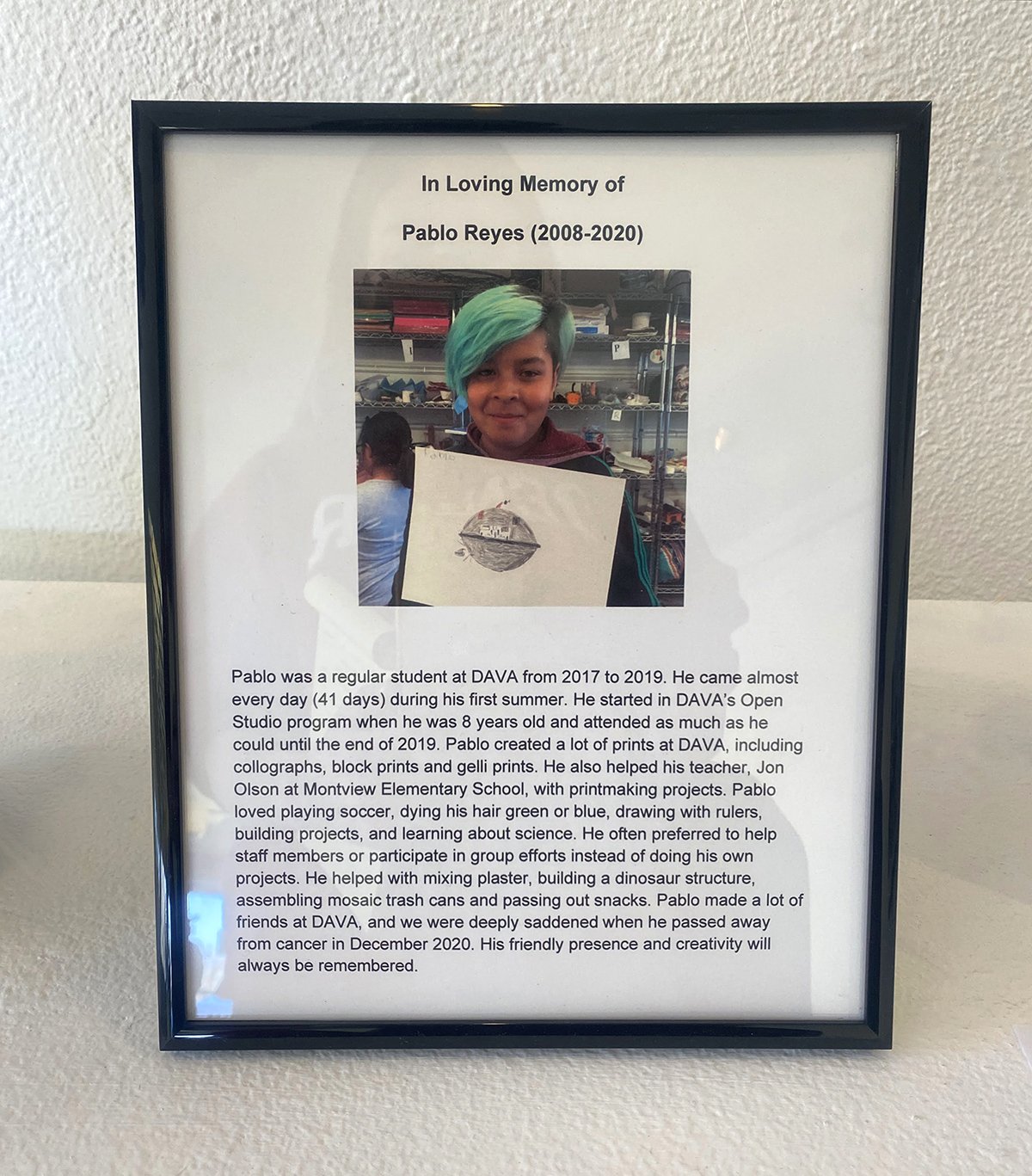

A tribute to DAVA student artist Pablo Reyes. Image by Ashten Scheller.

In addition to the professional artists featured in In Between, DAVA has also included a beautiful tribute to one of their own students who passed away from cancer in 2020: Pablo Reyes. Pablo began coming to DAVA when he was eight years old, in 2017, and quickly became a beloved, engaged, passionate student. Many of his own prints are on display as part of this printmaking show. They exist not only as a memorial, but their inclusion in the show truly emphasizes how community-oriented this institution is.

I am thrilled to be given a tour through the entire facility by Le Courtois, which allows me to see both students and professional artists alike in action, just on the other side of the gallery’s walls. This is a place of gathering and of creating—and not only in the physically artistic sense: community and relationships have been, and continue to be, created here. In Between is a stunning showcase of local talent, but equally so, it is an incredible invitation into the larger DAVA space, where all are welcome, regardless of their identity.

Ashten Scheller is a Denver-based art historian, writer, and researcher, as well as a volunteer assistant editor for the intersectional online arts platform Femme Salée. She holds a BA in Art History and International Studies from the University of Denver and a Master’s degree in Art History, Theory, and Display from the University of Edinburgh.

[1] From Javier Flores’ artist biography in the gallery wall text.

[2] From Salinas’ artist biography in the gallery wall text.

[3] From Carlisle Davidson’s artist biography in the gallery wall text.

[4] Ibid.

[5] From Perez’s artist biography in the gallery wall text.

[6] For more information, see https://www.nea.org/advocating-for-change/new-from-nea/racist-beginnings-standardized-testing.