Colombia: The Corn, the River, and the Grave

Colombia: The Corn, the River, and the Grave

Museo de las Americas

861 Santa Fe Drive, Denver, CO 80204

March 16–August 20, 2023

Admission: $8

Review by Djamila Ricciardi

Museo de las Americas has been a fixture within the local art scene for 32 years, [1] and continues to highlight relevant and under-told stories through images and objects that expand our collective view of what it means to be part of The Americas. [2] Their most recent exhibition features 13 international artists and two artist collectives who together “represent Colombia’s cultural diversity as well as its geographic differences.” [3]

It is truly an expansive survey that “emphasizes the interconnectedness of people and nature and the contradictions of that connection.” [4] It is rare that artwork produced in one location can transcend time and geography to connect with local viewers on such a visceral, human level. Presented in collaboration with independent curator and native Colombian Alex Brahim, Museo de las Americas offers Colombia: The Corn, the River, and the Grave—a far-reaching exhibition that seeks to reconcile with the ghosts of a nation’s past and look towards the future with hard-won hope and empathy.

An installation of view of Colombia: The Corn, The River, and the Grave at Museo de las Americas. Image by Marco Briones.

The construction of collective memory is a recurring theme at the heart of this exhibition. The curator deftly arranges this artwork like an archivist creates a body of records. Some of the artists selected to represent this particular slice of the Colombian contemporary art scene—including Jorge Luis Vaca Forero, Nadia Granados, Wilmer Useche, and Erika Diettes, all of whom are currently in their thirties or forties—employ a combination of approaches that highlight a biting sense of satire, a bitter taste for irony, and a clear eye for beauty in their respective commentaries on memory and national identity.

Colectivo Antónima (Tania Blanco + Aldo Hollmann), Vírgenes del monte (Virgins of the Mount), 2017, photography on paper. Image by Marco Briones.

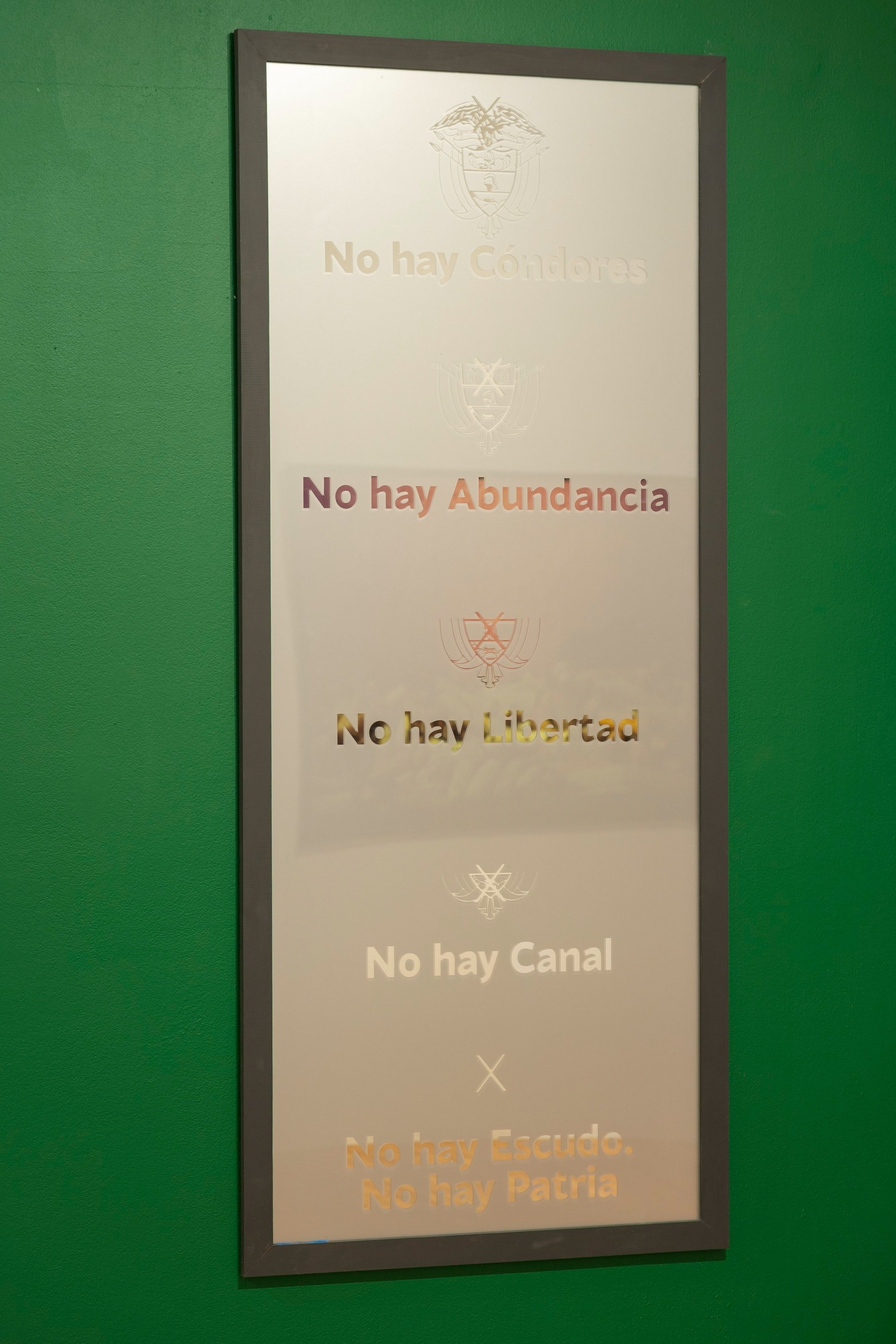

Walking through the gallery and standing before the individual works of art, one might find oneself wishing that there were more information available, perhaps in the form of bilingual interpretive text. This additional accommodation would help a museumgoer make sense of the complex history and concepts that these contemporary artists are grappling with. For instance, a monolingual English-speaking viewer might not easily piece together the textual clues present in Jorge Luis Vaca Forero’s Segunda lección (Second lesson) in order to understand that this artwork ought to be “read” from top to bottom, as each element represented on the coat of arms that adorns the national flag of Colombia is gradually erased. [5] The following words appear, in Spanish, on the sandblasted mirror:

“There are no condors.”

“There is no abundance.”

“There is no freedom.”

“There is no canal.”

“There is no shield. There is no homeland.” [6]

Jorge Vaca Forero, Segunda lección (Second lesson), 2019, sandblasted mirror. Image by Marco Briones.

These words reference the literal and metaphorical erosion of specific symbols of national identity. For example, the Andean condor, a bird that is considered sacred to the indigenous people of Colombia, is now critically endangered—threatened by accelerated deforestation, water pollution, and human-caused lead poisoning. [7] Accounting for a different kind of loss, there has been “no canal” since the United States forced Colombia to grant independence to the Department of the Isthmus of Panama back at the turn of the twentieth century; a geopolitical power move that continues to have significant economic ramifications in the region today. [8]

By peeling back these layers of meaning, the work takes on new life. Like the mirror upon which these words are etched, viewers can see their own reflection as well as the visual echoing of the conditions that affect the identity of this region. However, without the necessary context, the work runs the risk of having little impact.

An installation view of the exhibition with Nadia Granados’s Colombianización (Colombianization) project on the left. A mí me pagan por hablar bien de Colombia. Marca colombianización (They pay me to speak well about Colombia. Colombianization Brand), 2021, video, and La respuesta es Colombia. Un país en venta (The Answer is Colombia. A Country on Sale), 2022, video. Image by Marco Briones.

Another compelling set of works is part of a long-term performance-based project titled Colombianización (Colombianization) by artist Nadia Granados. Two television screens flank one of the gallery walls and show the films La respuesta es Colombia. Un país en venta (The Answer is Colombia. A Country for Sale) and A mí me pagan por hablar bien de Colombia. Marca colombianización (They Pay Me to Speak Well of Colombia. Brand Colombianization). In these videos, created in 2021 and 2022 respectively, Granados appears dressed in a formal business suit and mimics the “masculine” voice of “authority.” In a sharp and clear cutting way, the artist questions the patriarchal values of her native country and openly mocks advertising campaigns that celebrate “Colombianness” only to further exploit the country’s natural resources for the personal gain of a select business elite.

Perhaps the curator Alex Brahim reveals an aspect of his own past by including Granados in this show. Before becoming involved in socially-engaged art practices, he went to Bogotá to study marketing and advertising, stating, "marketing and advertising were my window into how empathy could be used to sell a product.”[9] However, as bell hooks reminds us, “advertising is one of the cultural mediums that has most sanctioned lying….our passive acceptance of lies in public life, particularly via the mass media, upholds and perpetuates lying in our private lives.” [10]

This is the crux of this work and the artist’s unique persona. Granados stands in front of a rapt audience in what looks like a TED-style talk and spouts jingoisms and hyperboles—describing Colombia as “a model of progress and development,” home to a “mega diversity supermarket” of natural resources, ripe for the taking and ready to be “reborn for investment.” [11] Never mind the kidnappings, the persistent insurgencies, legislative dysfunction, or all the unmarked graves.

Erika Diettes, Río abajo (Downriver), 2015, digital photography series printed on glass. Image by Marco Briones.

Despite periods of ceasefires, protracted peace processes, legal reforms, and electoral stability—the undeniable fact of death and disappearance permeates the consciousness of this nation’s citizens. Artist Erika Diettes creates a poignant tribute to victims of homicide and their families with Rio abajo (Downriver). In this photographic series, she creates freestanding structures that depict articles of clothing dredged up from river bottoms and rescued from the edges of streams.

Erika Diettes, Río abajo (Downriver), 2015, digital photography series printed on glass. Image by Marco Briones.

These pieces of fabric, suspended in clear water and illuminated in an otherworldly manner, are all that is left of a person. These are modern reliquaries and haunting bits of evidence that “show the reality of the country's rivers: one of the largest cemeteries in Colombia and perhaps the world.” [12] This is not easy art to take in and process, as it becomes impossible to turn away from a delicately crocheted dress and not wonder “why?”

Carlos Uribe, ¡Destapen! ¡Destapen! (Uncover! Uncover!), 2008, installation with digital photography adhered to flooring. Image by Marco Briones.

Speaking in a diverse chorus of regional dialects that collectively form español colombiano, [13] it is as if these artists are recalling the words of Toni Morrison and saying something like: “I know the world is bruised and bleeding, and though it is important not to ignore its pain, it is also critical to refuse to succumb to its malevolence. Like failure, chaos contains information that can lead to knowledge—even wisdom. Like art.” [14]

The artists assembled in this exhibition seek to do more than merely historicize the tragic legacy of decades of widespread violent conflict and corruption. Rather, they are confronting the chaos directly and doing their utmost to make sense of the wreckage while honoring the sacrifices of previous generations. Such is the task of artists living in troubled times. Sadly, Colombia is not the only country that is currently facing the devastating impacts of generations of civil conflict and environmental degradation. Perhaps, through the language of art, positive social change can become a reality.

Djamila Ricciardi (she/her) is a fifth generation Denverite who is actively involved in the local arts community. She graduated with a degree in Art History from Scripps College in Claremont, California and is an appreciator of all forms of creative expression.

[1] Bennito L. Kelty, “Museo De Las Americas Director Claudia Moran Sets Her Sights on Expansion,” Westword, Apr 21, 2023, https://www.westword.com/arts/museo-de-las-americas-director-expansion-denver-art-district-santa-fe-16564689.

[2] “America” refers to more than just the United States of America. It also includes the lands of the Western Hemisphere (North America and South America), composed of numerous entities and regions variably defined by geography, politics, and culture.

[3] From the Press Release for the exhibition: https://museo.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/NEW-The-Corn-the-River-and-the-Grave-Press-Release_Final-Edits.pdf.

[4] Ibid.

[5] This piece is actually a direct reference to a well-known artwork called Primera lección (First lesson), 1971, by the politically-minded, conceptual Colombian artist Bernardo Salcedo (1939–2007). See Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary, https://tba21.org/Primera_Leccion.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Alexey Zhúkov, “Why Is the Condor of the Andes in Danger of Extinction?” Latin American Post, Jan 27, 2023, https://latinamericanpost.com/37584-why-is-the-condor-of-the-andes-in-danger-of-extinction.

[8] “Separation of Panama from Colombia,” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, Apr 4, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Separation_of_Panama_from_Colombia.

[9] El Espectador, “Alex Brahim, Tejiendo Puentes Con Arte y Cultura,” ELESPECTADOR.COM, Nov 29, 2021, https://www.elespectador.com/el-magazin-cultural/alex-brahim-tejiendo-puentes-con-arte-y-cultura/.

[10] bell hooks, All about Love: New Visions (William Morrow, an Imprint of HarperCollins Publishers, 2022), 47.

[11] All quotes from Nadia Granados’ film: A mí me pagan por hablar bien de Colombia. Marca colombianización (They Pay Me to Speak Well of Colombia. Brand Colombianization), 2021.

[12] Erika Diettes, “Drifting Away - Photographs and Text by Erika Diettes,” LensCulture, https://www.lensculture.com/articles/erika-diettes-drifting-away.

[13] Joanna Gonzalez, “The Curious Case of Colombian Spanish: Fluentu Spanish Blog.” FluentU Spanish, Jul 10, 2022, https://www.fluentu.com/blog/spanish/colombian-spanish/.

[14] Toni Morrison, “No Place for Self-Pity, No Room for Fear,” The Nation, Dec 23, 2019, https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/no-place-self-pity-no-room-fear/.