African America: Contempt of Greasy Pigs

André Ramos-Woodard: African America: Contempt of Greasy Pigs

east window SOUTH

4949 Broadway, Unit 102-C, Boulder, Colorado 80304

January 11-March 29, 2022

Admission: Free

Review by Emily Zeek

On December 30, 2021, a fast-moving fire ripped through 1600 acres of land in Boulder County. Within a couple of hours, 1200 properties went up in flames and lives were indelibly changed. While the cause of the fire remains under investigation, what is known is that the origins of the fire were at the compound of a little-known white supremacist cult called Twelve Tribes that operates a restaurant in Boulder called the Yellow Deli. [1]

While driving to Boulder from Denver I witnessed the destruction firsthand. The Twelve Tribes, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center, “is a Christian fundamentalist cult born in the American South in the 1970s … that teaches its followers that slavery was ‘a marvelous opportunity’ for black people, who are deemed by the Bible to be servants of whites, and that homosexuals deserve no less than death.” [2]

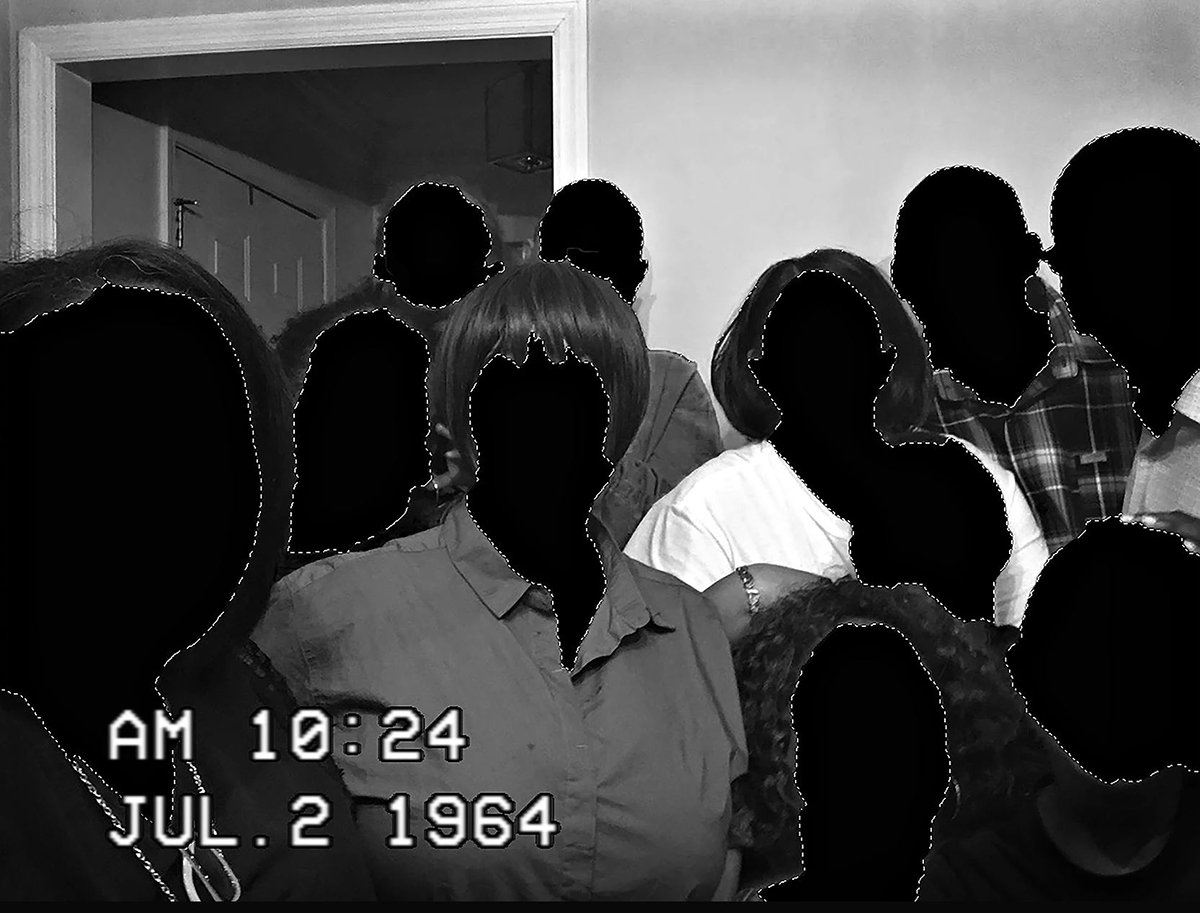

An installation view of east window SOUTH featuring André Ramos-Woodard’s exhibition African America: Contempt of Greasy Pigs. Image courtesy of east window SOUTH.

While Boulder has been harboring this hate-filled group—to its own detriment as the fires may illustrate—there are those in the community who are actively combatting and bringing light to the damage that these regressive, violent philosophies have on marginalized people and ultimately on all of us. In the first exhibition at east window SOUTH, emerging artist André Ramos-Woodard presents a straightforward and concise visual display of the ongoing struggle of African Americans at the hands of cops through photographic collages, ubiquitous images from social media, and a video projection.

The fifteen photographic works of art and the video in African America: Contempt of Greasy Pigs make up the inaugural exhibition in the newly opened gallery east window SOUTH managed by Todd Herman. East window refers to the window in Herman’s studio space where he began doing curation in 2020. Inspired by window displays he observed while living in San Francisco, the window gallery was made inevitable by COVID’s indoor restrictions in 2020.

André Ramos-Woodard, Things Fall Apart, 2021, photography and collage, 24 x 36 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

Herman, a photographer and filmmaker, has expanded the public-facing window gallery with the addition of a small gallery in the unit behind his studio. Contrasting with the white background of east window, east window SOUTH features black walls. It has the feeling of a darkroom or the explicit back room of a video store where a clearer picture of America’s reality is developed in private, intimate quarters.

It was during the pandemic—as Ramos-Woodard, who is non-binary, explains in a phone interview—that they and their brothers started running for exercise. While they were all living in various parts of the country, it gave them something to bond over. Tragically, they also watched the footage of Ahmaud Arbery getting killed in Georgia while jogging—an experience that hit home and made the struggle against racial violence feel that much more visceral. This inspired the video piece Haulin’ Ass.

André Ramos-Woodard, Weapon—Zimmerman Sold The Gun That Killed Trayvon Martin For A Quarter-Million Dollars, 2021, photography and collage, 24 x 30 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

Other works in the exhibition feature images of Breonna Taylor—the Black woman killed by police when they raided her house—allusions to the outstretched arms of Michael Brown, and the Skittles that Trayvon Martin was holding before he was killed. The exhibition illustrates the pervasive details of the stories of these murders, which have morphed into an overarching aesthetic of our time. In the ways that marches and speeches by MLK came to define the aesthetic of the civil rights era, victims of police brutality and the associated imagery have come to symbolize current fights for racial justice.

Stills from André Ramos-Woodard’s Haulin’ Ass, 2021, single channel video, 4:40 minutes. Images courtesy of the artist.

Haulin’ Ass is a bit nauseating, as handheld recordings can be. But in this case the disorienting quality of the work complements the intention of the show and the stomach-turning nature of America’s racist past. The sound of pained breathing communicates the exhaustion people of color feel as they continue to chip away at establishing racial justice in a country whose foundations were so oppressive, and where the current reality continues to be so violent.

As Ramos-Woodard explains, “This is the shit we experience and it is not fun.” African America: Contempt of Greasy Pigs does not shy away from depicting a negative image. Ramos-Woodard asserts “the system is set up against us and something has to be done.” By enlarging this “negative” in the space of east window SOUTH, Herman continues to build upon an inclusive ethos he’s been exploring in his personal work, which deals with disability justice and more recently with moral emotions like shame and disgust. [3]

André Ramos-Woodard, White Privilege. Black Trauma., 2021, digital collage, 11 x 14 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

Despite working together with Herman for the east window SOUTH exhibition, Ramos-Woodard retains a natural distrust for working with white people who have inflicted so much trauma. Ramos-Woodard explains, “I do not trust white people to authentically tell that story or further the issue alone.” In some ways the fierce anger and frustration displayed in Ramos-Woodard’s works complements the shame emotion—perhaps felt by a remorseful and contentious white male oppressor—that Herman explores in his work.

Ramos-Woodard grew up in Nashville, Tennessee and went to college in Beaumont, Texas at Lamar University. Growing up, Ramos-Woodard says their family was “pro-Black” in what they call a supportive rather than militant way. They recollected experiencing racist encounters with a friend’s mom who forbid a relationship simply because she didn’t like Black people or her kid hanging around them.

André Ramos-Woodard, Which one of y’all doesn’t see color?, 2021, photography and collage, 24 x 30 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

But it was in 2018 and 2019 when Ramos-Woodard went to graduate school in New Mexico that they were first confronted with demographics that were so overwhelmingly white. Beaumont Texas is 48% Black and Nashville is 28% Black while Albuquerque is only 3% Black. [4] Within this context and in the setting of freedom in graduate school, the issues of identity, racism, and queerness began to take hold in their work.

And in 2020 when the murder of George Floyd was recorded and broadcast over social media, Ramos-Woodard explains how it changed everything for them. The artist deepened their investigation into why things are the way they are and why they have to be this way.

André Ramos-Woodard, New Year’s Resolution, 2020, archival inkjet print, 16 x 24 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

Around the same time, Herman moved to Boulder with his family from San Francisco, where he continues to keep a rental property that allows him to maintain his studio in Boulder. As a child, Herman leant into and captured conflict photographically while playing with childhood friends—in one memory he shares with me—even staging a fight for photographic intrigue.

Herman conceives of his identity currently with an awareness of the privilege he brings to the art world. His artistic practice aims to leverage his position of privilege to lessen and deconstruct hierarchies through inclusion, providing opportunities for marginalized people to explore their voices, even with the inherent irony of being a landlord on the side.

When I ask Herman whose side is he on, he hesitates though, explaining “it would be arrogant of me to blindly take the side of André. I haven’t lived that experience.” He concedes that many may want him to be an accomplice, but he prefers instead to complicate the issue rather than to take sides. The website for east window, however, features eloquent anti-oppression statements of solidarity.

An installation view of André Ramos-Woodard’s exhibition African America: Contempt of Greasy Pigs. Image courtesy of east window SOUTH.

Ramos-Woodard, while physically detached from the Boulder gallery from his home in Texas, cannot afford to be emotionally detached from a struggle that impacts him so directly. But so far, he muses, the response to his work has been supportive and positive. He even welcomes the chance to defend himself from more hostile critics. If that were to occur, Herman explains, he would take the opportunity to speak with those who may find the work provocative and offensive.

But witnessing the passive destruction the fires caused in this region, we realize that the hostility and animosity may not appear in words, but rather through devastating, uncontrollable actions. The realities of Ramos-Woodard’s show and the allyship of Todd Herman at east window SOUTH poses a question to us all: how do we protect one another in a world of violent, destructive philosophies?

Emily Zeek is a transmedia and social practice artist from Littleton, Colorado who works with themes of feminism, sustainability, and anti-capitalism. She has a BFA in Transmedia Sculpture from the University of Colorado Denver and a BS in Engineering Physics from the Colorado School of Mines.

[1] From “Marshall fire investigation spotlights Twelve Tribes religious sect”: https://www.denverpost.com/2022/01/06/twelve-tribes-marshall-fire-investigation/

[2] From “Into Darkness: Inside an American White Supremacist Cult”: https://www.splcenter.org/fighting-hate/intelligence-report/2018/darkness.

[3] See Todd Herman’s Bio on the east window website: https://eastwindow.org/who.

[4] The five largest ethnic groups in Albuquerque, New Mexico are White (Non-Hispanic) (38.5%), White (Hispanic) (35.8%), Other (Hispanic) (9.45%), American Indian and Alaska Native (Non-Hispanic) (3.87%), and Asian (Non-Hispanic) (3.01%).